There are some good histories of the Linguistic Circle of Prague, which met in the years before the Second World War, and which included Russian scholars as well as ones from Czechoslovakia. Jindřich Toman’s The Magic of a Common Language is a particularly useful guide. Roman Jakobson, Nikolai Trubetzkoy, René Wellek and Vilém Mathesius were regular attendees to the circle. In 1929, the group founded a journal, Travaux du Cercle Linguistique de Prague.

Émile Benveniste presented a paper to the Linguistic Circle of Prague on 8 March 1937. His topic was “Linguistic expression of quantity (grammatical number and numerals)”. It presented some of the material he had first used in his second 1935-36 course at the Collège de France, while he was deputising for Antoine Meillet, whom he would later succeed in 1937 to the chair of Comparative Grammar. He never published the talk, telling Jakobson that the materials were lost when his flat was occupied during the war. (Benveniste spent most of the war either as a prisoner of war or in exile in Switzerland.) He confessed to Jakobson he did not have the courage to return to projects he had completed but never published. He did revisit one incomplete project, saying that he had to reconstitute its data from scratch, but that seems to have been an exception. Jakobson recounts this story both in an unpublished interview (which I’ve seen in the Tzvetan Todorov archives in Paris, but I understand is also in Jakobson’s archive at MIT) and in a note to his edition of Trubetzkoy’s letters to him. Trubetzkoy died in Vienna in 1938 from a heart attack, brought on by Nazi persecution. A volume of the Travaux du Cercle linguistique du Prague was dedicated to Trubetzkoy in 1939, and Benveniste was one of the contributors. His piece then was not the one on quantity, but an analysis of phonology and the distribution of consonants in words. Given Trubetzkoy’s major contribution to linguistics was in phonology, the choice of topic was appropriate, though Benveniste presumably did not know that that Trubetzkoy had told Jakobson he found Benveniste’s writings on phonology “usually not very successful” (10 January 1937).

In this text Benveniste works through examples from Latin, Ancient Greek and modern Persian, before suggesting some connections to the languages of Asia Minor, and from them back to what can be reconstructed of Proto Indo-European, before broadening the analysis in the final pages to languages outside of the Indo-European family. These examples show that even at this early stage of his career he already had an interest in native American languages. (Benveniste would do linguistic fieldwork in the Pacific northwest in the early 1950s.) He closes with the comment that his brief remarks indicate a need for a fuller study, but this is yet another example of one of his possible projects interrupted and then seemingly abandoned due to the war.

The Travaux du Cercle linguistique series ceased publication with the invasion of Czechoslovakia and the exile of many of the circle’s members. Jakobson fled in March 1939, first to Denmark, then later to Norway, Sweden and the United States. At one point he thought he might move to England, and he was supported by the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning. He recounts that he burned all of his papers in Brno shortly before the Nazi invasion, saving just the letters from Trubetzkoy, which were put in a briefcase, buried and retrieved after the war. It was this correspondence that Jakobson published many years later, in the original Russian with an English apparatus. The book has been translated into French. Jakobson and Benveniste corresponded after the war, and those letters have been published. But the destruction of Benveniste and Jakobson’s pre-war letters, as well as nearly all of Jakobson’s letters to Trubetzkoy, leaves important gaps in the record.

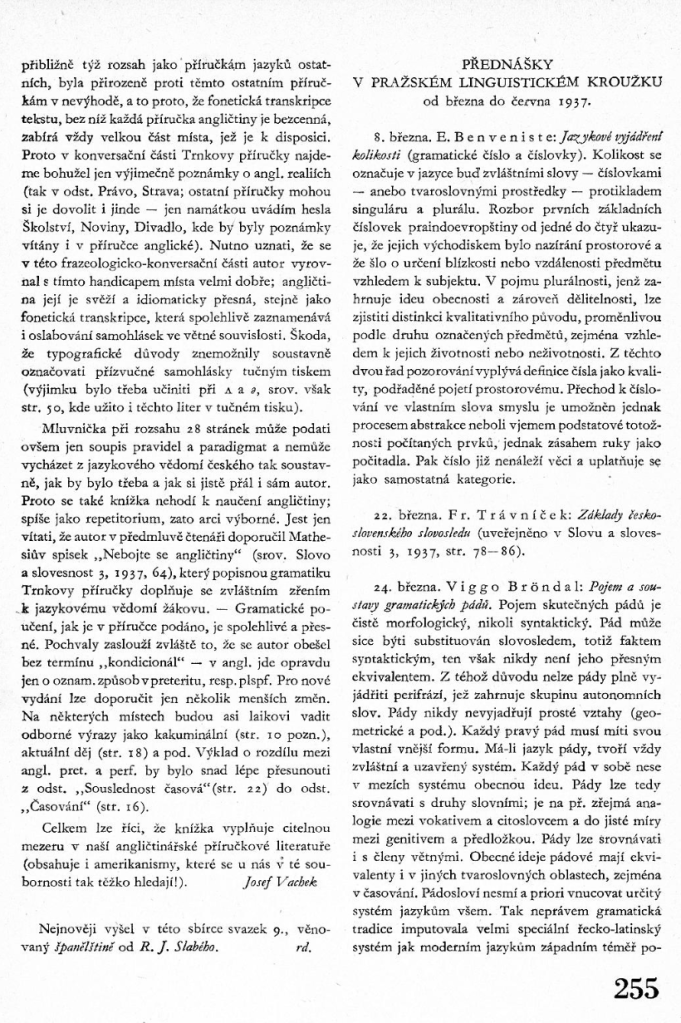

Jakobson’s note to Trubetzkoy’s letter about Benveniste and phonology mentions that a brief Czech summary of Benveniste’s 1937 lecture was published in the Circle’s journal Slovo a slovesnost. I was surprised to find this online. As far as I can tell, this is the only surviving trace of what Benveniste said in Prague, presumably itself a translation of a lost French original:

8. března. E. Benveniste: Jazykové vyjádření kolikosti (gramatické číslo a číslovky). Kolikost se označuje v jazyce buď zvláštními slovy — číslovkami — anebo tvaroslovnými prostředky — protikladem singuláru a plurálu. Rozbor prvních základních číslovek praindoevropštiny od jedné do čtyř ukazuje, že jejich východiskem bylo nazírání prostorové a že šlo o určení blízkosti nebo vzdálenosti předmětu vzhledem k subjektu. V pojmu plurálnosti, jenž zahrnuje ideu obecnosti a zároveň dělitelnosti, lze zjistiti distinkci kvalitativního původu, proměnlivou podle druhu označených předmětů, zejména vzhledem k jejich životnosti nebo neživotnosti. Z těchto dvou řad pozorování vyplývá definice čísla jako kvality, podřaděné pojetí prostorovému. Přechod k číslování ve vlastním slova smyslu je umožněn jednak procesem abstrakce neboli vjemem podstatové totožnosti počítaných prvků, jednak zásahem ruky jako počitadla. Pak číslo již nenáleží věci a uplatňuje se jako samostatná kategorie.

March 8 [1937]. E. Benveniste: Linguistic expression of quantity (grammatical number and numerals). Quantity is indicated in language either by special words – numerals – or by morphological means – the opposition of singular and plural. An analysis of the first basic Proto-Indo-European numerals from one to four shows that their starting point was spatial perception and that it was a matter of determining the proximity or distance of an object relative to the subject. In the concept of plurality, which includes the idea of generality and at the same time divisibility, it is possible to detect a distinction of qualitative origin, variable according to the type of objects indicated, especially with regard to their animacy or inanimacy [životnosti nebo neživotnosti – literally life or non-life or livingness]. From these two series of observations follows the definition of number as a quality, a concept subordinate to that of space. The transition to numbering in its proper sense is made possible both by the process of abstraction, or the perception of the essential identity of the counted elements, and on the other hand by the intervention of the hand as a counter [počitadla – calculator or abacus]. Then the number no longer belongs to the thing and is applied as a separate category.

[Many thanks to John Raimo for the translation of this text.]

In their apparatus to the Benveniste and Jakobson correspondence, Chloé Laplantine and Pierre-Yves Testenoire note that on the 12 March 1937, Benveniste gave a lecture on the structure of Proto-Indo-European to the Masaryk University in Brno, on Jakobson’s invitation (pp. 140-41). Jakobson wrote a brief report on this lecture for the Lidové noviny newspaper on 16 March: “Prof. Benveniste v Brně”. The text is reprinted in Jakobson’s Selected Writings (Vol IX, Part II, p. 246). The lecture seems to have been mainly for non-specialists, and to have summarised some of Benveniste’s Paris teaching and publications. Jakobson indicates that Benveniste stressed the coherence of his views with those of the Czechoslovak school, talked of the relation of Hittite to Proto-Indo-European, and stressed some of the grammatical functions lacking in the reconstructed language. He also adds that Benveniste, together with the Norwegian Slavic scholar Stang – Christian Schwigaard Stang – visited Brno’s Town Hall and other sites.

References

Émile Benveniste, “Přednášky v Pražském linguistickém kroužku od března do června 1937”, Slovo a slovesnost III, 1937, 255, http://sas.ujc.cas.cz/archiv.php?lang=en&art=229

Émile Benveniste, “Répartition des consonnes et phonologie du mot”, in Études phonologiques dédiées à la mémoire de M. le Prince N.S. Trubetzkoy, Prague: Jednota Československých Matematiků a Fysiků, 1939, 27-35; reprinted in Benveniste, Langues, Cultures, Religions, eds. Chloé Laplantine and Georges-Jean Pinault, Limoges: Lambert-Lucas, 2015, Ch. 12.

Roman Jakobson (ed.), N.S. Trubetzkoy’s Letters and Notes, The Hague: Mouton, 1975; Correspondance avec Roman Jakobson et Autres Écrits, trans. Patrick Sériot and Margarita Schönenberger, Lausanne: Payot, 1996.

Roman Jakobson, “Prof. Benveniste v Brně”, Selected Writings Vol IX: Uncollected Works, 1916–1943, Part Two, 1934–1943, ed. Jindřich Toman, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2014, 246.

Chloé Laplantine and Pierre-Yves Testenoire (eds.), “La correspondance d’Émile Benveniste et Roman Jakobson (1947-1968)”, Histoire Épistémologie Langage 43 (2), 2021, 139-68, https://journals.openedition.org/hel/1284

Patrick Sériot, Structure and the Whole: East, West and Non-Darwinian Biology in the Origins of Structural Linguistics, trans. Amy Jacobs-Colas, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2014.

Jindřich Toman, The Magic of a Common Language: Jacobson, Mathesius, Trubetzkoy, and the Prague Linguistic Circle, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1995.

Archives

Fonds Tzvetan Todorov, Bibliothèque nationale de France, NAF 28949, https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc104829j

Roman Jakobson papers, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Distinctive Collections, MC-0072, https://archivesspace.mit.edu/repositories/2/resources/633

—-

This is the third post of an occasional series, where I try to post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome. The other posts so far are:

Benveniste, Dumézil, Lejeune and the decipherment of Linear B – 5 January 2025

Foucault’s 1972 visit to Cornell University – 12 January 2025 (updated 14 January)

Marie-Louise Sjoestedt (1900-1940): an important scholar of Celtic languages and mythology – 26 January 2025

Thomas Sebeok, Umberto Eco and the Semiotics of Nuclear Waste – 2 February 2025

Vladimir Nabokov, Roman Jakobson, Marc Szeftel and The Song of Igor – 9 February 2025

Ernst Kantorowicz and the California Loyalty Oath – 16 February 2025

The full list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Benveniste, Dumézil, Lejeune and the decipherment of Linear B | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Foucault’s 1972 visit to Cornell University | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Marie-Louise Sjoestedt (1900-1940): an important scholar of Celtic languages and mythology | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Thomas Sebeok, Umberto Eco and the Semiotics of Nuclear Waste | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Sunday histories – short essays on Progressive Geographies | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Vladimir Nabokov, Roman Jakobson, Marc Szeftel and The Song of Igor | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 26: Benveniste’s late publications; Sunday Histories; beginning archival work in the United States | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Ernst Kantorowicz and the California Loyalty Oath | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Walter B. Henning, Robert Oppenheimer, Ernst Kantorowicz, the Institute for Advanced Study and the Khwarezmian Dictionary Project | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: The Friendship between Hannah Arendt and Alexandre Koyré | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Alexandre Koyré’s Wartime Teaching at the École Libre des Hautes Études and the New School | Progressive Geographies