Although they both studied in Germany, and were among those who attended Heidegger’s lecture courses in the 1920s, Hannah Arendt and Alexandre Koyré didn’t meet at that time. (Arendt attended lectures in 1924-26 in Marburg; Koyré in 1928-29 in Freiburg.) Their first contact seems to have been after Arendt had left Germany in 1933, when she moved to Paris where Koyré was teaching at the École Pratique des Hautes Études. Teaching records of the EPHE show that Arendt’s husband at the time, Günter Stern (Anders), attended Koyré’s classes. Their friendship, though, seems to have really developed only after Arendt moved to the United States. Hannah Arendt’s biographer Elisabeth Young-Bruehl describes Alexandre Koyré as “a close friend” (p.117).

Koyré spent much of the Second World War in the USA, teaching at the New School and the École Libre des Hautes Études, and then was a frequent visitor afterwards, holding visiting positions at several US institutions including University of Chicago, Johns Hopkins University, and the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. Although Arendt taught at both Chicago and the New School, that was from 1963-67 and 1967-75, and Koyré died in 1964, so they did not overlap. But throughout the 1950s and early 1960s they would meet in both the US and when Arendt was in Europe. Young-Bruehl says that Arendt was invited by Koyré and Jean Wahl to speak to the Collège Philosophique in Paris after the war, but she found the social side of these visits too much (p. 245; citing a letter from Arendt to Hilde Fränkel on 3 December 1949). Arendt was pretty critical about French intellectuals generally, and some of her letters to her second husband Heinrich Blücher are often rude about them. But she seems to have genuinely liked Koyré and his wife.

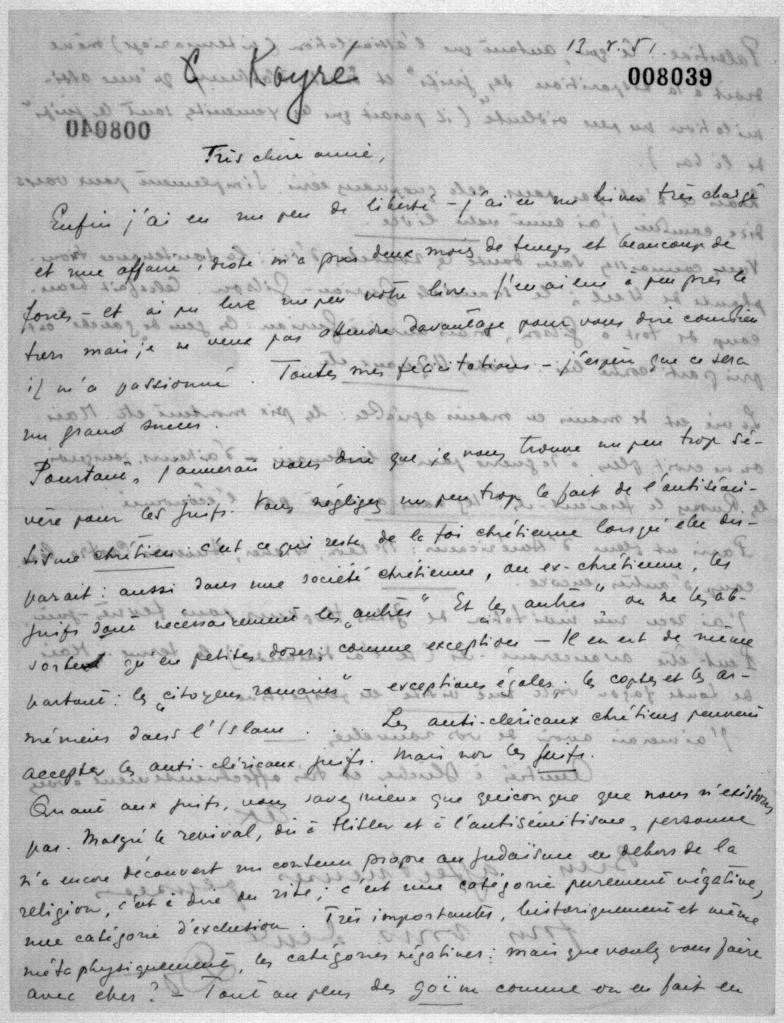

What survives of the Arendt-Koyré correspondence is interesting – it is available as a scan online at the Library of Congress, which holds Arendt’s archives; and was published by Paola Zambelli, Koyré’s biographer, in 1997. But it only covers the years 1951-63, and what survives are only Koyré’s letters to Arendt. As I’ve said before, I understand there is little correspondence in Koyré’s archives. Zambelli provides a useful introduction to the letters. Koyré wrote to Arendt in French – one of their shared languages. (Koyré corresponded with another German-born US philosopher, Horace M. Kallen, in English, and he knew German well.) An English translation of the Koyré-Arendt letters would be worthwhile, I think; perhaps also an edition of the Koyré-Kallen letters.

Here, though, I won’t discuss the Koyré letters to Arendt, or Zambelli’s useful introduction, but just mention a few other traces of their friendship I know. Arendt tells Gershom Scholem that she had arranged for copies of Scholem’s Major Trends in Jewish Scholarship to go to a range of contacts in France, based on a list that Koyré had put together (19 March 1947). One of those copies was to Koyré himself, and Arendt tells Scholem on 30 September 1947, that:

I just had a long talk with Koyré, who just arrived to give lectures at Chicago University. – (By the way, I like him very much.) About reviews of your book in France: Koyré himself is writing one for the Revue Philosophique.

I don’t think that review ever appeared. Arendt’s marked-up copy of Scholem’s book is available online from Bard College. In a letter to Karl Jaspers, Arendt writes of her delight that Koyré has contacted her on 4 October 1950: “Koyré called out of nowhere this morning; great glee”.

There are some potentially interesting thematic links between their work. One would be the political lie, on which both Koyré and Arendt wrote. This is work which has been revisited in more recent times, including the reprint of Koyré’s text in October in 2017, and the renewed attention to Arendt’s work on totalitarianism. Jacques Derrida discussed both Koyré and Arendt in his lecture “History of the Lie: Prolegomena”, which exists in a few different forms including in Without Alibi. (A version of this lecture was, incidentally, one of the two times I heard Derrida speak.)

Another shared interest would be technology and spatiality. Arendt’s copy of Koyré’s 1957 book From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe is preserved as part of her library, and the marked-up pages have been made available online. Arendt cites the work in The Human Condition, published the following year, and on their shared understandings the best sources I know are essays by Waseem Yaqoob and Bernard Debarbieux.

I am beginning work on Koyré’s other correspondence, and have found few mentions of Arendt. But he does tell a friend in 1959 he is looking forward to Arendt visiting Princeton, where she will be the “first woman professor” (see the report in Princetonia). There are few other traces of the friendship with Koyré in the correspondence of Arendt, at least in that which I have seen. Arendt told Jaspers of Koyré’s death in 1964, which she had learned of though Anne Weil.

Annchen wrote that Koyré had died. I don’t know whether you knew him. An old friend of ours. Sad. I saw him a year ago in Paris after he’d had a stroke that aged him a lot. Then, Annchen wrote, he had bone cancer. So—thank God.

Anne Weil was a childhood friend of Arendt, who was married to the philosopher Éric Weil. Weil dedicated his Logique de la philosophie to Koyré, and they are mentioned in Koyré’s letters to Arendt. Éric Weil was also a co-editor of Critique with Georges Bataille. More connections and networks to explore.

References

Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958.

Hannah Arendt, Crises of the Republic: Lying in Politics; Civil Disobedience; On Violence; Thoughts on Politics and Revolution, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher, Within Four Walls: The Correspondence between Hannah Arendt and Heinrich Blücher, ed. Lotte Kohler, trans. Peter Constantine, New York: Harcourt, Inc., 1996.

Hannah Arendt and Karl Jaspers, Correspondence 1926-1969, eds. Lotte Kohler and Hans Saner, trans. Robert and Rita Kimber, San Diego: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1992.

The Correspondence of Hannah Arendt and Gershom Scholem, ed. Marie Luise Knott, trans. Anthony David, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Bernard Debarbieux, “Les Spatialités dans l’œuvre d’Hannah Arendt”, Cybergeo : revue européenne de géographie, 2014, https://doi.org/10.4000/cybergeo.26277

Jacques Derrida, “History of the Lie: Prolegomena”, Without Alibi, trans. Peggy Kamuf, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002, 28-70.

Alexandre Koyré, “Réflexions sur le mensonge”, Renaissance I, 1943, 95-111; revised version as “The Political Function of the Modern Lie”, Contemporary Jewish Record 8 (3), 1945, 290-300; reprinted in October 160, 2017, 143-51.

Alexandre Koyré, From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1957.

Alexandre Koyré, “Lettres à Hannah Arendt (1951-1963)”, ed. Paola Zambelli, Nouvelles de la république des lettres 13 (1), 1997, 137-56; introduced by Paola Zambelli, “Koyré, Hannah Arendt et Jaspers”, 131-37.

Samantha Rose-Hill, Hannah Arendt, London: Reaktion, 2021.

Waseem Yaqoob, “The Archimedean Point: Science and Technology in the Thought of Hannah Arendt, 1951-1963”, Journal of European Studies 44 (3), 2014, 199-224.

Elisabeth Young-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2ndedition, 2004 [1982].

Paola Zambelli, Alexande Koyré in Incognito, Firenze: Leo S. Olschki, 2016; trans. Irène Imbart, Alexandre Koyré, un juif errant? Firenze: Musée Galileo, 2021.

Archives

Hannah Arendt Papers. Library of Congress: Correspondence, 1938-1976; General, 1938-1976

– Fränkel, Hilde, 1949-1950, undated, https://www.loc.gov/item/mss1105600172

– Koyré, Alexandre, 1951-1963, https://www.loc.gov/item/mss1105600214

Hannah Arendt Personal Library, Bard College, https://blogs.bard.edu/arendtcollection/

Fonds Alexandre Koyré, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales archives, Humathèque Condorcet, https://cak.ehess.fr

This is the ninth post of an occasional series, where I try to post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome. The other posts so far are:

Benveniste, Dumézil, Lejeune and the decipherment of Linear B – 5 January 2025

Foucault’s 1972 visit to Cornell University – 12 January 2025 (updated 14 January)

Benveniste and the Linguistic Circle of Prague – 19 January 2025

Marie-Louise Sjoestedt (1900-1940): an important scholar of Celtic languages and mythology – 26 January 2025

Thomas Sebeok, Umberto Eco and the Semiotics of Nuclear Waste – 2 February 2025

Vladimir Nabokov, Roman Jakobson, Marc Szeftel and The Song of Igor – 9 February 2025

Ernst Kantorowicz and the California Loyalty Oath – 16 February 2025

Walter B. Henning, Robert Oppenheimer, Ernst Kantorowicz, the Institute for Advanced Study and the Khwarezmian Dictionary Project – 23 February 2025

The full list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Alexandre Koyré’s Wartime Teaching at the École Libre des Hautes Études and the New School | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Hannah Arendt, David Farrell Krell and the early English translations of Heidegger | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Sunday histories – short essays on Progressive Geographies | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 27: more archive work on Saussure, Blanchot, Foucault, Jakobson and Koyré, two recordings, and a talk at the University at Buffalo | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 27: more archive work on Saussure, Blanchot, Foucault, Jakobson and Koyré, two recordings, and a talk at the University at Buffalo | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Alexandre Koyré in Cairo | Progressive Geographies