The story sounds like a detective novel or a spy thriller. A professor of the history of religion at the University of Chicago is shot at close range in the third-floor bathroom of Swift Hall in 1991. The killing is seemingly professional, and the assassin is never found.

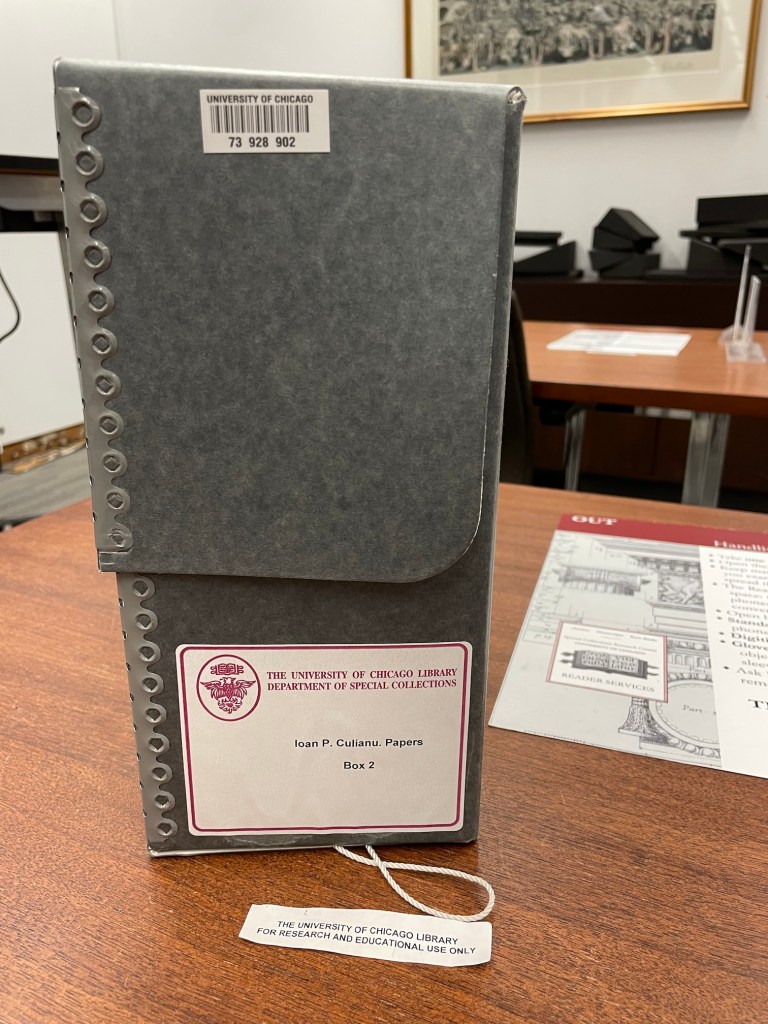

Ioan Culianu (sometimes Couliano) was 41, at the early stage of what seemed to be a brilliant career. Born in Romania, he had written an Italian thesis on Hans Jonas, worked on Gnosticism and mysticism, wrote fiction, and is best known in English for his 1987 book Eros and Magic in the Renaissance. He had come to Chicago initially as a visitor to work with the Romanian-born historian of religion Mircea Eliade, who taught at Chicago for thirty years. Eliade wrote a preface to Eros and Magic in the Renaissance. After Eliade died in 1986, Culianu was appointed to a position in Chicago, initially temporarily, then made permanent. Eliade’s will, which is in Culianu’s archive (box 2, folder 6), made Culianu and his nephew Sorin Alexandrescu his literary executors, giving them the right to publish materials from his archive and complete unfinished projects. The extent to which that was allowed if Eliade’s widow objected is much debated. Both Culianu and Eliade’s papers are held by the University of Chicago, in the Hanna Holborn Gray special collections research center. Culianu did publish some of Eliade’s work, but while once a disciple and uncritical defender of his reputation, over time became critical of his political affiliations before and during the Second World War. At the time of his death Culianu was investigating far-right politics in Romania more generally, shortly after the violent overthrow of the Nicolae Ceaușescu regime.

After a shorter article in 1992, the investigative reporter Ted Anton wrote a book in 1996 about the story, Eros, Magic and the Murder of Professor Culianu. It’s a biography of Culianu, using the murder as a framing device around the story of his move to the West and his career. It draws out the much-discussed links Eliade had to the fascist Iron Guard in Romania. It was founded initially as the Legion of the Archangel Michael, and Eliade wrote in the pre-war period in support of their policies. He also held diplomatic posts in London and Lisbon during the Second World War.

In Culianu’s case, some fellow exiles conjectured, the Iron Guard would have feared Culianu because he had been named executor of Eliade’s unpublished scholarly papers. They might have feared he would use his position to undermine his mentor’s reputation by publishing the wrong documents. But by 1991 the Eliade papers had long since been dispersed, mostly under the care of Regenstein Library. Eliade’s uncompleted volumes had either been edited and published or shelved. There were no secret Iron Guard papers.

Concerning the whispered rumors, Paris dissident Monica Lovinescu put it best: “Whenever they say it’s the Iron Guard,” she observed, “you can be sure it’s Securitate” (p. 263).

Anton’s book was reviewed in The New York Review of Books by none other than Umberto Eco. (This is the second time recently I’ve written about a story that sounds like it is from one of his novels. For the other, on Thomas Sebeok’s ideas about the semiotics of nuclear waste, and the idea of an atomic priesthood, see here.) Eco, who knew Culianu a little, offers some mild criticisms of Anton, in particular of his use of reconstructed dialogue in what is supposed to be a historical account, not a “fictionalized biography”. As he suggests, “Anton does not adopt the deductive method of Sherlock Holmes and his story suggests Lovecraft more than Conan Doyle”. But he too focuses on the possible security involvement in Culianu’s murder:

Though he harbors no monarchist notions, Culianu meets former King Michael of Romania and becomes convinced that the return of the monarchy can perhaps restore a constitutional stability to the country. He receives many warnings: phone calls, letters, threatening incidents such as a break-in at his house. Some of them he dismisses; others worry him; perhaps at a certain point, he thinks, he can no longer avoid some sort of political role. He is killed in a manner typical of the methods of Eastern European security services.

Eco also notes that the story of Culianu, only a few years after his death, has already become a myth, “that could have been convincingly conceived (and studied) only by the victim himself if he had remained with us. But he would have told it, no doubt, with tongue in cheek”. Eco is also intrigued though slightly irritated by a recent Italian novel that blends “true events and fiction” in telling Culianu’s story.

In 2023, Bruce Lincoln, professor emeritus of the History of Religion at the University of Chicago, whose PhD was supervised by Eliade, wrote another book on the case. Lincoln has been very critical of Georges Dumézil and his politics, so his work was already important to my project. But before this book he had been, I thought, uncritical of Eliade, who has an even more troubled political past than Dumézil. Indeed, one of the criticisms of Dumézil is the company he kept, and his support for Eliade after the Second World War is one of the charges made against him. Eliade was unable to return to Communist Romania after the war because of his fascist past and Dumézil provided a lot of support – giving him teaching opportunities, introducing Eliade to publishers, and helping with the French translations of his work. Eliade’s politics was known in France at that time through other Romanian émigrés (Lincoln, p. 47).

Shortly before his death, Culianu had entrusted some English translations of some politically compromising articles by Eliade to a colleague (Lincoln, p. 1). That colleague had, in time, passed them to Lincoln. Lincoln admits that when he retired and cleaned out his office, he threw out the Eliade papers by mistake. His book is an attempt to make good on this blunder. He plans to publish the articles in some form once they are free from copyright restrictions (pp. 5-7). His book is a detailed and careful exposure of the intertwined Eliade and Culianu cases. His explanation of Eliade seems plausible:

Over the years he laboured, never with more than partial success, to persuade himself and others of two propositions: first, he had done nothing wrong, since he was not really a Nazi or an anti-Semite; second, that those who said otherwise did so out of envy, malice, and unprincipled ideological commitments. Beyond that, he was caught in a bind. Were he to acknowledge his past support for the Legion, strong condemnation would follow from many quarters, regardless of what mitigating explanations he might offer. And were he to express any regrets, make any apologies, or distance himself in any way, legionaries would likely see him as a traitor and could well take vengeance on him (p. 72).

At times it is the kind of forensic history of ideas approach that Eco seemed to want – more Conan Doyle than eldritch horror. It tracks the changing positions Eliade took about his politics; those which Culianu took in coming to terms with what he discovered about Eliade; and carefully sifts the different interpretations of Culianu’s murder. Lincoln assesses the Iron Guard, Securitate and other possibilities, and while he rules none out, is unconvinced by any. Towards the end he offers this statement:

It has never been my intention to play detective and solve the murder of Ioan Petru Culianu. By a circuitous route, a set of documents made its way from his hands to mine. For many years I ignored them, and in a moment of carelessness, I lost them. What I have done since and what I present here is an attempt to atone for my lapses (p. 132).

Some correspondence Lincoln collected for his book was not included in it, but is available as a download on his academia.edu page. It’s a useful supplement to the book. The planned publication in English of the Eliade articles will complete the dossier of the book and these letters.

I was recently at the University of Chicago to work in the archives, mainly with parts of the Eliade papers. Dumézil’s correspondence with Eliade is quite extensive, even though the letters all date from after Eliade’s years in Paris. This makes sense, they would have seen each other regularly at that time, but it is also undoubtedly because of what material was, and was not, kept. I had seen a few of Eliade’s letters to Dumézil in Paris at the Collège de France, though letters are in different boxes and folders, filed with teaching records and by year, rather than by correspondent. Some of the Dumézil-Eliade letters have been published, but not, I think, all. So, it was a worthwhile trip for that alone.

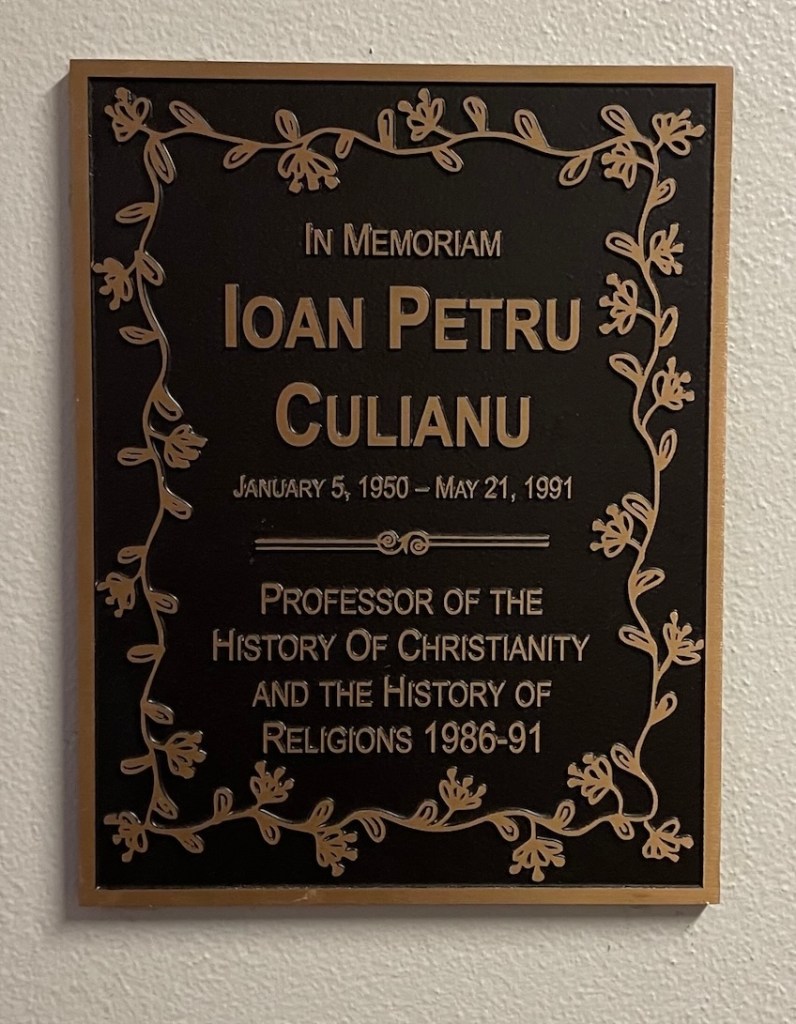

The Regenstein Library was not far from Swift Hall, so I went there on one of the lunchbreaks. This was where Eliade taught, where Dumézil was a visitor in the 1969-70 academic year, and which had an extensive divinity library. There is a plaque commemorating Culianu outside the bathroom. (I’m curious, but not as much as the Toilet Guru, who has documented the murder story with photographs and much more on his site.) Eliade’s office was nearby, at the Meadville-Lombard seminary – the building has since been sold and is no longer used by the University. This is where, shortly before his death, there was a fire which destroyed some of his papers and much of his library. There are quite a lot of fire-damaged documents in his archives – some with just burnt edges, but a few more badly-damaged scraps are in plastic wallets. It seems likely this fire was a result of an ashtray on his desk, rather than anything more sinister, although Eliade apparently took it as an omen.

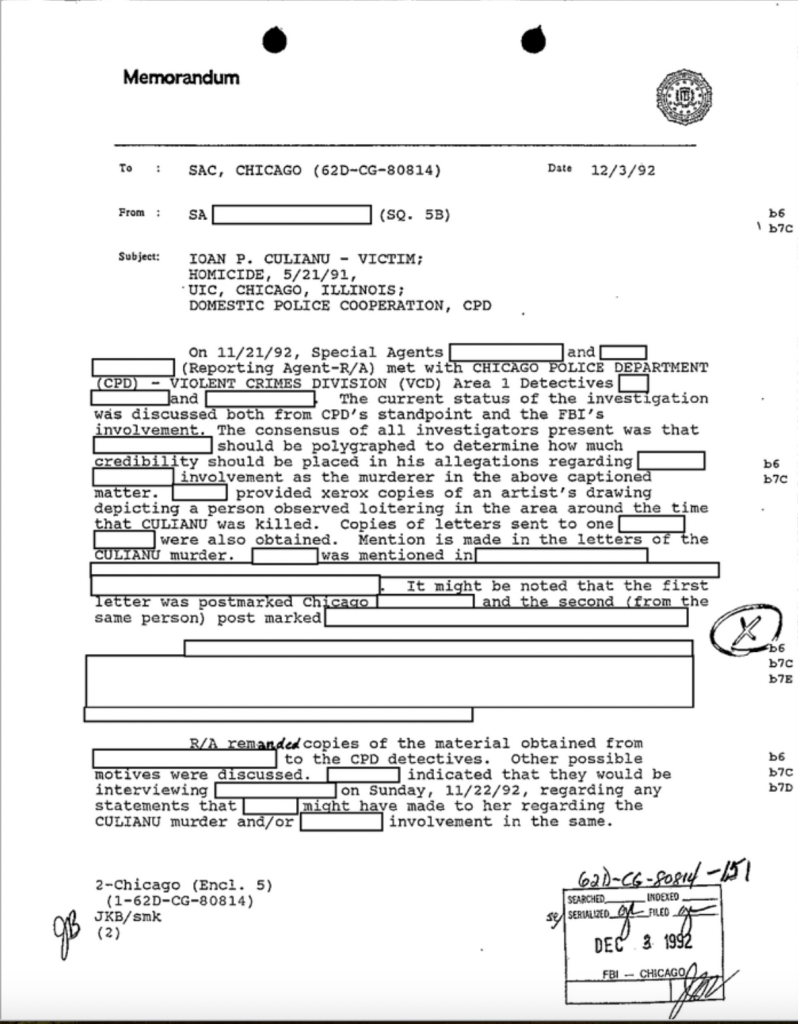

For those wanting to follow in Anton and Lincoln’s footsteps, the FBI files on Culianu are partly available online. The FBI vault website lists three files, of 489, 324 and 227 pages, although the second and third appear to be entirely blank if you download them, though can be read online. As with other FBI files I’ve seen, there is a lot of repetition, several coversheets and pro forma, newsclippings, and much is redacted.

Eco’s irritation with the Italian novel was in part, he recognised, because the story was so recent. It has since been the subject of at least one other fictionalisation in Romania. Andrei Terian discussed the Italian and Romanian versions in a short essay in 2014. Lincoln’s more recent and serious book has brought attention back to the story – it was the initial spur to my thinking about the case again, though I’d heard of it when first reading about Eliade. Almost thirty-five years after the killing, it seems unlikely more evidence will come to light. In a Chicago theme, the hotel I was staying in had a few books left in the room, one of which was Saul Bellow’s last novel Ravelstein, named after Abe Ravelstein, who is based on the story of Allan Bloom. Both Bloom and Bellow taught at Chicago, as part of the Committee on Social Thought. The book has a character, Radu Grielescu, who is a very thinly disguised version of Eliade, and briefly mentions the murder.

Update February 2026: For a more general discussion of his work, see Umberto Eco, Philosophers, Mythologists and Linguists

References

Ted Anton, “The Killing of Professor Culianu”, Lingua Franca 2 (6), 1992.

Ted Anton, Eros, Magic and the Murder of Professor Culianu, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1996.

Saul Bellow, Ravelstein, New York: Penguin, 2015 [2000].

Ioan Peter Couliano, Eros et magie à la Renaissance, Paris: Flammarion, 1984; Eros and Magic in the Renaissance, trans. Margaret Cook, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Umberto Eco, “Murder in Chicago”, trans. William Weaver, The New York Review of Books, 10 April 1997, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1997/04/10/murder-in-chicago/

Mircea Eliade, “Préface”, in Ioan Culianu, Eros et magie à la Renaissance, Paris: Flammarion, 1984, 5-7; Eros and Magic in the Renaissance, trans. Margaret Cook, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1987, xi-iii.

Christopher E. Koy, “Travel for the Dying: Ceauşescu’s Romania as Seen by Saul Bellow”, Review of International American Studies RIAS 17 (2), 2024, 161-75.

Bruce Lincoln, Secrets, Lies, and Consequences: A Great Scholar’s Hidden Past and his Protégé’s Unsolved Murder, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2023.

Andrei Terian, “On the Romanian Biographical Novel: Fictional Representation of Mircea Eliade and Ioan Petru Culianu”, Revista Transylvania 12, 2014, 5-9, https://grants.ulbsibiu.ro/wsa/data/III.9_Terian.pdf

Toilet Guru, “The University Bathroom Assassination of Ioan Culianu”, https://toilet-guru.com/ioan-culianu/

Cristina Vatelescu, Police Aesthetics: Literature, Film and the Secret Police in Soviet Times, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2010.

Archives

Ioan P. Culianu Papers, University of Chicago Library, https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/scrc/findingaids/view.php?eadid=ICU.SPCL.CULIANU

Mircea Eliade Papers, University of Chicago Library, https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/scrc/findingaids/view.php?eadid=ICU.SPCL.ELIADEM

FBI files, Ioan Culianu, https://vault.fbi.gov

“Unpublished Appendices to Bruce Lincoln, Secrets, Lies, and Consequences: A Great Scholar’s Hidden Past and his Protégé’s Unsolved Murder (Oxford University Press, 2023)”, academia.edu (includes Correspondence among Mircea Eliade, Ioan Culianu, Mac Linscott Ricketts, Adriana Berger, Ivan Strenski, and others, 1977-91)

This is the nineteenth post of a weekly series, where I post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome.

The full list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Sadly Alphonso Lingis has died. People may not be familiar with his work but he was instrumental in seeding Continental philosophy here in the US and a very generous scholar.

https://library.oapen.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12657/25547/1004548.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Pingback: Alphonso Lingis, in memoriam | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 28: archives in Princeton, Chicago and final work in New York | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Sunday histories – short essays on Progressive Geographies | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Six Months of ‘Sunday Histories’ – weekly short essays on Progressive Geographies | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Books received – Febvre, Hiltebeitel, Comaroff, Kantorowicz, Glyph 7, Gadoffre, Eliade & Couliano, Harvey | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Umberto Eco, Philosophers, Mythologists and Linguists | Progressive Geographies