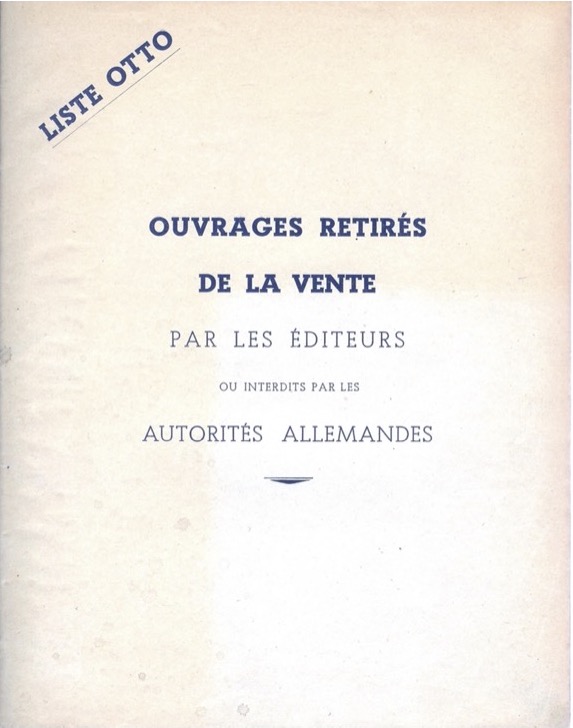

The “Liste Otto” was named after Otto Abetz, German ambassador to France under the Occupation, from August 1940 until the Liberation. The list indicated which books had to be removed from sale, with existing copies destroyed, after the German invasion of France. The September 1940 version replaced an earlier “Liste Bernhard”, and it was followed by a supplement, and two later versions in 1942 and 1943. The original version had the title “Ouvrages retirés de la vente par les éditeurs ou interdits par les autorités allemandes [Works withdrawn from sale by publishers or banned by the German authorities]”. One of the reasons some French presses pre-emptively removed books from their lists was in the hope they would be allowed to continue selling other works. In 1942 the list had the bilingual title “Unerwuenschte Franzoesische Literatur/Ouvrages Littéraires Français non désirables”, in 1943 “Unerwuenschte Literatur in Frankreich/Ouvrages Littéraires non désirables en France”.

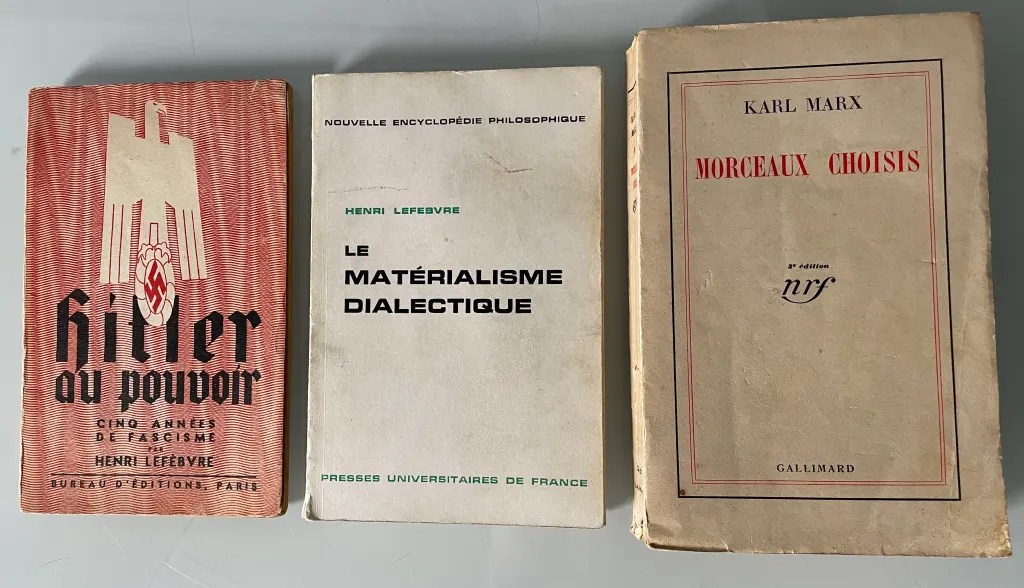

The September 1940 list includes, unsurprisingly, Henri Lefebvre’s book Hitler au pouvoir, published in 1938. The Hitler book was a critical, Marxist assessment of five years of fascism in Germany. Its inclusion in a prohibited list was hardly surprising, but is only one aspect of the censorship of Lefebvre’s work. The list also includes Cahiers de Lénine sur la dialectique de Hegel (1938) and Karl Marx’s Morceaux choisis (1934), both of which Lefebvre had edited with Norbert Guterman.

Guterman was Jewish, so this alone would have been enough for inclusion on this list. But Lefebvre’s 1939 book on Nietzsche, his Le Nationalisme contre les Nations (1937) and the collection of texts he and Guterman had edited by Hegel (1938) are not on the lists, and neither is their co-authored book La conscience mystifiée (1936). In the third edition of the list in 1943, Lefebvre’s book Le Matérialisme dialectique (1940) was added.

There is therefore something of an arbitrary nature of the list – there are obviously reasons why the Nazi occupiers would object to those books they did include, but those reasons would also seem to apply to ones they did not. The Nietzsche book, for example, is very much written as a challenge to the fascist appropriation.

After Le Matérialisme dialectique in 1940, Lefebvre did not publish another book until L’Existentialisme in 1946. For someone who usually published a book or two a year, this was quite a long break – the only comparable disruption to his regular publishing rhythm came when he was having difficulties with Communist Party censors in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He was clearly storing up ideas during the war, as in 1947 he published five books – two on Marx, the first volume of his Critique de la vie quotidienne(Critique of Everyday Life), a study of Descartes and Logique formelle, logique dialectique.

During the war, Lefebvre moved back to the Pyrenees, working with the resistance – although the exact nature of his role is debated – and doing the research for what turned into his doctoral thesis in 1954. The primary thesis was on peasant communities and was published posthumously (Les Communautés paysannes Pyrénéennes); the second thesis was a historical and geographical study of one small area, La vallée du Campan, part of which is included in the On the Rural collection I co-edited with Adam David Morton in 2022.

One indication of the censorship Lefebvre experienced in the war comes in the original 1947 edition of Critique de la vie quotidienne. On the page ‘Du même auteur’, Lefebvre lists his previous publications. There he distinguishes three ways his books were suppressed:

- seized and destroyed in October 1939 by order of the Daladier government

- seized and destroyed at the beginning of 1940 by the publisher

- seized and destroyed at the end of 1940 by the occupying authority, Liste ‘Otto’

Interestingly, he says Le Nationalisme contre les Nations was in the first category; Hitler and Nietzsche both in the second; Le matérialisme dialectique and the collections on Lenin and Hegel in the third. From the lists discussed above, this isn’t entirely correct, but it explains why the Nietzsche book was indeed removed from sale shortly after publication, and why copies are so hard to find today. The ‘Liste Otto’ did however usually list books withdrawn from sale by publishers, as well as ones the Germans banned.

Getting hold of some of these books can be challenging. They were often printed in limited numbers, and at least some copies were destroyed. While some have been reissued, the Hitler one never has been, and it was the last of Lefebvre’s books I was finally able to buy. The most easily accessible version is the Italian translation from 13 years ago – Hitler al potere. Cinque anni di nazismo in Germania. I first read the French book in the New York Public Library in 2002, since I don’t know of a copy in the UK, before getting the Italian translation and a photocopy of the French. I then later found an original copy in a second-hand bookshop. I say a bit more about the book here.

Le nationalisme contre les nations had a second edition in 1988; the Nietzsche book was reissued in 2003; Le materialisme dialectique has gone through multiple editions and was translated into English by John Sturrock. The Hegel collection is still in print, whereas the Marx collection was superseded by a two-volume collection of Oeuvres chosis edited by Lefebvre and Guterman in the 1960s.

The list of books by Lefebvre ‘En préparation’ in the Critique de la vie quotidienne list is also interesting – only a few of these were ever published. A full account of that is another story, involving censorship from the French Communist Party. Logique formelle, logique dialectique was supposed to be the first of an eight-volume series, under the working title of Traité du Matérialisme dialectique. The second volume, entitled Méthodologie des sciences, was written in the late 1940s but only published in 2002. In Logique formelle, logique dialectique Lefebvre gives an indication of six further volumes (pp. 11-12; see Elden, Understanding Henri Lefebvre, 27-28).

In the Critique de la vie quotidienne list the titles are different:

- Théorie de la Connaissance: logique et méthodologie

- Matérialisme historique

- Dialectique dans l’étude du Capital et de l’Etat

- L’humanisme

- Psychologie et théorie de l’individualité

- Esthétique

Lefebvre published on the state, aesthetics and history at later points in his career, but only his Contribution à l’esthétique, written in the late 40s and published in 1953, comes close to the plan of this series. Lefebvre also mentions as forthcoming a history of rural France with Albert Soboul; La Conscience privée: étude sur l’histoire et la structure sociale de l’individualité; and L’Homme et le Soldat. A fragment of La Conscience privée was included in the third edition of La Conscience mystifiée, but neither of the others appeared. Adam David Morton and I briefly mention the planned project with Soboul in the Introduction to On the Rural (p. xiii).

The other side of the books that were banned is the story of those that were published during the war. That probably deserves another post, but in my project on Indo-European Thought in France, there are some authors who continued to publish under the Occupation, working with presses who were submitting their titles to censorship. Some intellectuals refused those constraints; others continued. Some presses worked closely with the authorities, a murky history well told in, for example, accounts of Abetz by Martin Mauthner and Barbara Lambauer. There was also the question of paper shortages, which continued for some time after the war, introducing another limit, since not all presses had access to supplies, and those that did had to be even more selective in what they published. There is therefore a politics and political economy of publishing in this period, of which the story has, I think, best been told by Pascal Fouché, in L’Édition française sous l’Occupation 1940-1944 and Gisèle Sapiro, The French Writers’ War, 1940-1953.

References

Cynthia D. Bertelsen, “Liste Otto: Banning Books in WWII France”, April 2024, https://gherkinstomatoes.com/2024/04/14/liste-otto-banning-books-in-wwii-france

Jean-François Dubos, “La « liste Otto » : guerre aux livres”, Revue historique des armées 307, 2022, 123-28.

Stuart Elden, Understanding Henri Lefebvre: Theory and the Possible, London: Continuum, 2004.

Stuart Elden, “Some Are Born Posthumously: The French Afterlife of Henri Lefebvre”, Historical Materialism14 (4), 2006, 185-202 (originally published as “Certains naissent de façon posthume: La survie d’Henri Lefebvre”, trans. Élise Charron and Vincent Charbonnier, Actuel Marx 36, 2004, 181-98).

Pascal Fouché, L’Édition française sous l’Occupation 1940-1944, Paris: Bibliothèque de Littérature française contemporaine, two volumes, 1987.

G.W.F. Hegel, Morceaux choisis, trans. and ed. Henri Lefebvre and N. Guterman, Paris: Gallimard, 1939.

Henri Lefebvre, Le Nationalisme contre les Nations, Paris: Editions Sociales Internationales, 1937; second edition, Paris: Méridiens Klincksieck, 1988.

Henri Lefebvre, Hitler au pouvoir: Les enseignements de cinq années de fascisme, Paris: Bureau d’Éditions, 1938; trans. Cristiano Casalini, Hitler al potere. Cinque anni di nazismo in Germania, Milano: Medusa, 2012.

Henri Lefebvre, Nietzsche, Paris: Editions Sociales Internationales, 1939; second edition, Paris: Éditions Syllepse, 2003.

Henri Lefebvre, Le Matérialisme dialectique, Paris: PUF, 1940; Dialectical Materialism, trans. John Sturrock, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009 [1968].

Henri Lefebvre, Critique de la vie quotidienne (Introduction), Paris: Éditions Bernard Grasset, 1947; reedition in 1958 with new introduction; Critique of Everyday Life, trans. John Moore, London: Verso, 1991.

Henri Lefebvre, Logique formelle, logique dialectique, Paris: Anthropos, second edition, 1969 [1947].

Henri Lefebvre, La vallée du Campan: Étude de sociologie rurale, Paris: PUF, 1963.

Henri Lefebvre, L’Existentialisme, second edition, Paris: Anthropos, 2001 [1946].

Henri Lefebvre, Contribution à l’esthétique, Paris: Anthropos, second edition, 2001 [1953].

Henri Lefebvre, Méthodologie des sciences: Un inédit, Paris: Anthropos, 2002 [c. 1947].

Henri Lefebvre, Les Communautés paysannes Pyrénéennes: Thèse soutenue en Sorbonne en 1954, Navarrenx: Cercle Historique de l’Arribère, 2014.

Henri Lefebvre and Norbert Guterman, La Conscience mystifiée, third edition, Paris: Éditions Syllepse, 1999 [1936].

Henri Lefebvre, On the Rural: Economy, Sociology, Geography, eds. Stuart Elden and Adam David Morton, trans. Robert Bononno et. al., Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022.

Barbara Lambauer, Otto Abetz, ou l’envers de la collaboration, Paris: Fayard, 2001.

V.I. Lenin, Cahiers de Lénine sur la dialectique de Hegel, Paris: Gallimard, 1938, revised edition Paris: Gallimard, 1967.

Karl Marx, Morceaux choisis, ed. Henri Lefebvre and N. Guterman, Paris: Gallimard, 1934.

Martin Mauthner, Otto Abetz and his Paris Acolytes: French Writers who Flirted with Fascism, 1930-1945, Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2017.

Gisèle Sapiro, La Guerre des écrivains 1940-1953, Paris: Fayard, 1999; The French Writers’ War, 1940-1953, trans. Vanessa Doriott Anderson and Dorrit Cohn, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

Liste Bernhard and Liste Otto versions

All reproduced in Fouché, L’Édition française sous l’Occupation 1940-1944, Vol I, 287-340.

- Liste Bernhard, http://rlfsoa.wikidot.com/liste-bernhard

- Liste Otto, Ouvrages retirés de la vente par les éditeurs ou interdits par les autorités allemands, September 1940 Gallica; with two page supplement

- Unerwuenschte franzoesische Literatur/Ouvrages Littéraires Français non désirables, July 1942Gallica

- Unerwuenschte Literatur in Frankreich/Ouvrages littéraires non désirables en France, 10 May 1943 Gallica; Wikisource

- Index par auteurs Gallica

As an earlier version of this story from July 2023 indicated, I am correcting a mistake I’d made twenty years ago. I had said Lefebvre’s 1939 book Nietzsche was one of the books prohibited under the German Occupation (Understanding Henri Lefebvre, p. 8; “Some Are Born Posthumously”, p. 190), but as the account above shows, it is not one of the books on the “Liste Otto”. Understanding Henri Lefebvre has long been available as print-on-demand only, and keeps going up in price. Someone has uploaded a version here though. I hope what I’ve reported in this post is now accurate, but happy to receive additions or corrections.

This is the twenty-fifth post of a weekly series, where I post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome.

The full list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Henri Lefebvre’s 1939 book on Nietzsche and the ‘Liste Otto’ – which books of his were banned? | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Sunday histories – short essays on Progressive Geographies | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Six Months of ‘Sunday Histories’ – weekly short essays on Progressive Geographies | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Alexandre Kojève, Henri Lefebvre and the translation of Hegel’s Phenomenology | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 29: working on Benveniste’s Vocabulaire, Dumézil’s Bilan and other work | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Fernand Braudel and the Writing and Teaching of History in Captivity | Progressive Geographies