In Mitra-Varuna in 1940, Georges Dumézil mentions the equation of Ahura-Mazdāh and Varuna, which he says was a “hypothesis, long accepted without argument”, but which “has subsequently been hotly disputed – wrongly, in my belief”, and that “on this point I regret being in disagreement with a mythologist of such standing as H. Lommel” (French, p. 109; English, pp. 64-65). This a reference to Indologist and Iranologist Hermann Lommel (7 July 1885-5 October 1968), and specifically to a chapter in his 1935 book Die alten Arier: Von Art und Adel ihrer Götter [The Ancient Aryans: The Nature and Nobility of their Gods], translated into French as Les Anciens Aryans in 1943. Over thirty years later, Dumézil praised Lommel’s 1939 analysis of the relation between the Indian sorcerer Kāvya Uśanas and the Iranian king Kavi Usan, which he builds upon in a detailed analysis in the second part of the second volume of his Mythe et épopée series, a part translated as The Plight of the Sorcerer.

Lommel is an interesting figure. Extraordinarily, his mother was G.W.F. Hegel’s granddaughter, while his father was the physicist Eugen von Lommel. In his helpful Encyclopædia Iranica entry on Lommel, Rüdiger Schmitt notes his training at Göttingen by “Jacob Wackernagel (Indo-European), Hermann Oldenberg (Indology), and Friedrich Carl Andreas (Iranian studies)”, which puts him in a similar lineage to the one later followed by Walter Bruno Henning (on whom, see here).

After teaching for a few years in Göttingen, Lommel was a Professor at the Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main between 1917 and 1950, where he held a chair in Indo-European studies. Lommel was the German translator of Ferdinand de Saussure’s Cours de linguistique générale in 1931. Schmitt suggests that he “was one of the first German linguists who perceived the importance of the epoch-making work… and therefore translated it into German (1931) at a time when such translations were not yet common at all”. Roman Jakobson though is highly critical of Lommel’s translation, describing it as “frankly bad, sacrificing all theoretical finesse to the desire to Germanise Saussurean terminology and phraseology at all costs” (Selected Works, Vol VIII, 398).

Lommel is best-known for his work on Zoroastrianism. This includes his translations of Avestic texts – the Yašts in 1927 and the posthumous edition of the Gathas. He is also known for his own books on the topic, particularly his 1930 book Die Religion Zarathustras. As well as Die alten Arier, Dumézil praises his 1939 Die arische Kriegsgott [The Aryan God of War] in his own treatment of the warrior function (The Destiny of the Warrior, pp. xii-xiii). Die alten Arier was the first volume of a series edited by Lommel, “Religion und Kultur der alten Arier”, but as far as I can tell, the only other volume in that series was his own Die arische Kriegsgott.

The dating of Lommel’s focus on the Aryan is noteworthy, and certainly does not seem to have disadvantaged him, though I know of no links between him and the Nazi regime. His position at Göttingen seems to have been continuous through the Nazi period and the Second World War. The beginning of Die alten Arier notes the context: “We speak a lot in the present of Aryans, but we rarely think of the ancient Aryans, to whom this name in its proper sense applies and which are the origin of the very word” (p. 7). If he had left it at that, perhaps that would be defensible. But he continues:

We become profoundly aware of the origin and character of our people [Herkunft und Art unseres Volkes] and their rank among the peoples of humankind [unsere Stellung unter den Völkern der Menschheit]. But we must also, especially if we wish to adopt the name of Aryans for ourselves, become aware of what links us to the ancient Aryana and know their spiritual character (p. 7).

In the first chapter of the book, Lommel relates Aryan to what is called Indo-German in Germany (p. 19), which the French translation glosses as what is known as Indo-European elsewhere (p. 26). That is an equation which raises a host of issues. He goes on to limit Aryan to “Indo-European Indians and Iranians [die indogermanischen Inder und die Iraniene]” (p. 20). Other writers in this period, however, used “Aryan” without the accusations that such work today would produce. Jules Bloch’s linguistic study L’Indo-Aryen du Véda aux temps modernes dates from 1934, for example, and was translated into English as Indo-Aryan: From the Vedas to Modern Times in 1965, shortly after his posthumous Application de la cartographie à l’histoire de l’Indo-Aryen. Bloch was a colleague of Émile Benveniste at the École Pratique des Hautes Études and the Collège de France, and like Benveniste lost his teaching positions because they were Jewish. In contrast to Benveniste, who spent part of the war in exile in Switzerland, Bloch taught in Lyon and Toulouse during the war, due to the support of Vichy education minister and classics scholar Jérôme Carcopino. Both Bloch and Benveniste were reinstated in their Paris positions after the Liberation.

The Swedish academic Stig Wikander’s 1938 doctoral thesis Der arische Männerbund, only recently translated as The Aryan Männerbund, is different example. It is a book which is in dialogue with Benveniste and Louis Renou, Dumézil and Lommel, among others. It dates from the same year as what Dumézil would call his breakthrough to understand trifunctionalism, and Wikander is critical of Dumézil’s earlier work, particularly here his book on centaurs: “as often with him, the attempt shows a correct understanding of the mythological problem, but in the execution of his theses he rarely manages to come to entirely convincing results” (Der arische Männerbund, p. 100; The Aryan Männerbund, pp. 152-53). Dumézil would also be very critical of his own early work, reformulating it all in the light of trifunctionalism. He references Der arische Männerbund frequently, while Wikander builds on the trifunctional approach in his study of the Mahāhbhāta, in an essay Dumézil though very highly of and translated into French. They had a long-standing correspondence. (Benveniste, incidentally, reviewed Wikander’s book quite critically.)

Wikander’s focus in Der arische Männerbund was on the Indian and Iranian traditions, and was something of a development in those areas of Otto Höfler’s 1934 book KuItische Geheimbünde der Germanen. Höfler’s politics are relatively well-known since he was a member of Heinrich Himmler’s SS Ahnenerbe. The politics of Wikander have been questioned, with Mihaela Timuş saying that “Wikander’s private correspondence as well as his articles published in Swedish journals before the war provide concrete testimony on his ambiguous position on the Nazi political, as well as academic, situation”.

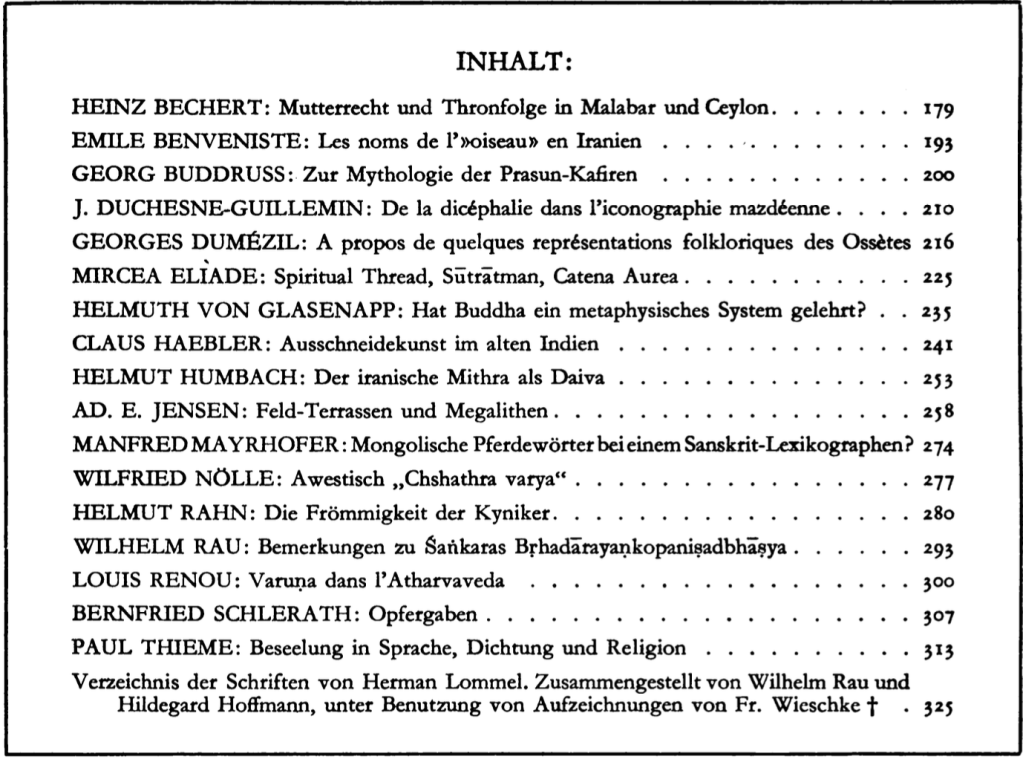

After the war, Benveniste, Dumézil and Mircea Eliade all contributed to Lommel’s Festschrift for his 75th birthday in 1960, which appeared both as a book and as a special issue of the journal Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde (open access). Other contributors included Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin, Renou, and Paul Thieme. His work was quite widely discussed. Benveniste especially makes use of Lommel’s translations of the Yašts, both in publications and teaching. He references him most regularly in his early The Persian Religion. (He also challenges his interpretation of the meaning of próbata in his Vocabulaire, but that’s a quite specific point not particularly relevant to this post.)

One way of perhaps marking the distinctions between these writers is that it is one thing to talk of an Indo-Aryan language, another to project that onto a people, and another to suggest an idealised racial profile with contemporary parallels. Bloch does the first; Lommel the second, at best; Höfler most fully embraces the third. Wikander is, I think, uncomfortably between the second and third positions. Dumézil almost never uses the term ‘Aryen’, except for a few instances in 1941, as detailed by Cristiano Grottanelli. That is something I will discuss in more detail elsewhere.

References

Émile Benveniste, The Persian Religion According to the Chief Greek Texts, Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1929.

Émile Benveniste, “Stig Wikander – Der arische Männerbund…”, Bulletin de la Société Linguistique de Paris 39 (2), 1938, 42-43.

Jules Bloch, L’Indo-Aryen du Véda aux temps modernes, Paris: Adrien Maisonneuve, 1934; Indo-Aryan: From the Vedas to Modern Times, trans. Alfred Master, Paris: Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1965.

Jules Bloch, Application de la cartographie à l’histoire de l’Indo-Aryen, eds. C. Caillat and P. Meile (Cahiers de la Société Asiatique, XIII), Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 1963.

Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin, “Wikander, Oscar Stig”, Enclyclopedia Iranica, 2009, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/wikander-oscar-stig/

Georges Dumézil, Heur et malheur du guérrier, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1969; The Destiny of the Warrior, trans. Alf Hiltebeitel, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Georges Dumézil, Mitra-Varuna: Essai sur deux représentations indo-européennes de la souveraineté, Paris: Gallimard, second edition, 1948 [1940]; Mitra-Varuna: An Essay on Two Indo-European Representations of Sovereignty, trans. Derek Coltman, ed. Stuart Elden, Chicago: HAU, 2023.

Georges Dumézil, Mythe et Épopée II: Types épiques indo-européens: un héros, un sorcier, un roi, Paris: Gallimard, 1971, 133-238; The Plight of the Sorcerer, ed. Jaan Puhvel and David Weeks, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1986.

Cristiano Grottanelli, “Dumézil’s Aryens in 1941”, Zeitschrift für Religionswissenschaft 6, 1998, 207-219.

Otto Höfler, KuItische Geheimbünde der Germanen, Frankfurt-am-Main: Verlag Moritz Diesterweg, 1934.

Roman Jakobson, Selected Writings, The Hague: Mouton & Co, nine volumes, 1962-

Herman Lommel, Die Yäšt’s des Awesta, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht/Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung, 1927.

Herman Lommel, Die Religion Zarathustras nach dem Awesta dargestellt, Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1930.

Herman Lommel, “Kāvya Uçan”, in Mélanges de linguistique offerts à Charles Bally, Geneva: Georg & Cie, 1939, 209-14, reprinted in Kleine Schriften, ed. Klaus Ludwig Janert, Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1978, 162-67.

Herman Lommel, Die alten Arier: Von Art und Adel ihrer Götter, Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann, 1935; Les anciens Aryens, trans. Pierre Beauchamp, Paris, Gallimard, 1943.

Herman Lommel, Die arische Kriegsgott, Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann, 1939.

Herman Lommel, Die Gathas des Zarathustra, ed. Bernfried Schlerath, Basel/Stuttgart: Schwabe & Co, 1971.

Herman Lommel, Kleine Schriften, ed. Klaus Ludwig Janert, Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1978.

Ferdinand de Saussure, Grundfragen der allgemeinen Sprachwissenschaft, ed. Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye with Albert Riedlinger, trans. Herman Lommel, Berlin and Leipzig: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1931.

Rüdiger Schmitt, “Lommel, Herman”, Encyclopædia Iranica, 2000, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/lommel-herman/

Bernfried Schlerath (ed.), Festgabe für Herman Lommel zur Vollendung seines 75. Lebensjahres am 7. Juli 1960 von Freuden, Kollegen und Schülern, Wiesbaden: Kommissionsverlag Otto Harrassowitz, 1960; also published as Paideuma: Mitteilungen zur Kulturkunde, 7 (4/6), 1960, https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40014729

Mihaela Timuş, “Wikander, Stig”, Encyclopedia, 2005, https://www.encyclopedia.com/environment/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/wikander-stig

Stig Wikander, Der arische Männerbund: Studien zur indo-iranischen Sprach- und Religionsgeschichte, Lund: Ohlsson, 1938; The Aryan Männerbund: Studies on Indo-Iranian Language and Religious History, trans. Tom Billinge, Sanctus Arya Press, 2024.

Stig Wikander, “Pāṇḍavasagan och Mahābhāratas mystiska förutsättningar”, Religion och Bibel 6, 1947, 27-39; “La Légende des Pândava et la substructure mythique du Mahābhārata”, trans. Georges Dumézil, in Dumézil, Jupiter Mars Quirinus IV: Explication de textes indiens et latins, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1948, 37-53, with commentary 55-100.

This is the 31st post of a weekly series, where I post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome.

The full list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 29: working on Benveniste’s Vocabulaire, Dumézil’s Bilan and other work | Progressive Geographies