I’ve been back in the UK for a few months, though I continue to work through the archival material I saw in the United States, some of which is in the form of notes, some photos of things, and a few scans requested from archives. I’ve also had a steady stream of things I ordered for duplication from archives, all of which are feeding into different parts of this project.

But I really needed to get back to working on the Benveniste part of Chapter 9, before moving to the Dumézil discussion. Roger Woodard asked me to write a chapter on “Benveniste, Dumézil and Indo-European Thought in Twentieth Century France”, for the Cambridge History of Mythology and Mythography, which he is editing. This was a useful exercise in trying to distil some of the overall claims I am making in my book manuscript. While Dumézil’s status as a mythologist is of course well established, this isn’t a conventional way of reading Benveniste. Silvia Fregeni has done the most extensive work in this register, and reading Benveniste as making contributions to sociology and anthropology alongside linguistics runs through my manuscript.

The most thorough work on this comes in Benveniste’s Vocabulaire – the Dictionary of Indo-European Concepts and Society. It’s a book I keep returning to, and have a discussion I’m now fairly happy with in place. I thought that with the discussion of the Vocabulaire it made sense not to use the same examples across the Cambridge chapter and the manuscript – there are so many interesting analyses that it is impossible to discuss them all. I’ve already posted here about how the book has things to say about territory, and in the book chapter I discuss the way Benveniste analyses “Hellenic Kingship” through a discussion of the words basileús and wánaks. Although basileus is the later word for king, Benveniste argues that earlier Mycenaean sources indicate that “the basileús was merely a local chieftain, a man of rank but far from a king”, without “political authority”, whereas the wánaks was “the holder of royal power” (Vocabulaire, Vol II, p. 24; Dictionary, p. 320). That changes in later Greek. I develop that reading a bit more here.

I had been debating what analyses to use in the book manuscript. I discuss hospitality, partly because I want to return to it as an example of how Derrida engages with the reading in a concluding chapter. I also want to say something about marriage and kinship, gift and exchange, and economic values, since these are themes he discussed in separate publications, and I think help with questions about the dating and composition of the text. I think this is sufficient to give a sense of the richness of the book.

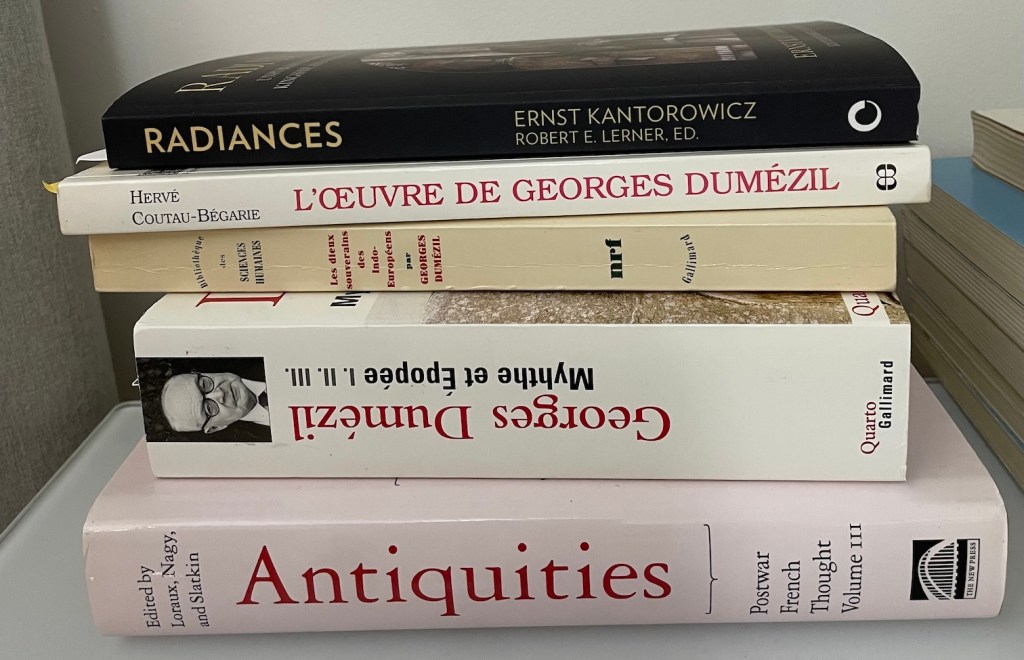

I then moved to discuss Dumézil’s works of his bilan period – a programme begun around the time of his retirement, where he produced consolidated, updated and extended analyses of the major themes of his career. There are various indications of what he had in mind, in a series of prefaces and other places. The series includes his massive Archaic Roman Religion, the first of his books to be translated into English, and the three volumes of Mythe et épopée, which is only partially available in English. (For a list of the parts available, see here, recently updated.) The bilan sequence also includes his updated versions on books on the warrior and Saxo Grammaticus, and some other works. I still have work to do on this, but I’m aiming to complete the draft this summer. This will leave Dumézil’s 1980s books, particularly the Esquisses series, and his later works on Caucasian linguistics, for separate discussions.

I had a week in Paris in early July, in which I worked through a series of boxes of the Émile Benveniste papers at the Bibliothèque nationale, mainly relating to the Vocabulaire book. I’ve seen all these boxes at least once before, but will need some time going back over things – the numerical order is neither chronological nor thematic, so now I know better where materials are I can go back in a more logical order. I also looked at a few folders at the Collège de France, mainly in relation to Benveniste. I’ll next be back in September.

Outside this project, I’ve been trying to keep commitments to a minimum. In late May I was part of a discussion of Chris Philo’s important new book Adorno and the Antifascist Geographical Imagination for the London Group of Historical Geographers. My piece should be published along with some other commentaries and a response from Chris. I have also written a short review of Juliet Fall’s remarkable book Along the Line: Writing with Comics and Graphic Narrative in Geography for a session at the Royal Geographical Society-Institute of British Geographers conference in Birmingham in late August, and revisited a lecture on Shakespeare for a book chapter. I have one more book review to write, on the new collection of Ernst Kantorowicz essays, but other than that, the two priorities for the foreseeable future are the Indo-European book manuscript and the work for the new translation and edition of Foucault’s Birth of the Clinic. I’ve been doing a little work on that.

I’ve also been continuing the ‘Sunday Histories’ series of posts. Some of these are not connected to this project, with updated pieces on Henri Lefebvre (here and here), or continuing the side-project on Foucault’s early reception in the United States (pieces on Josué Harari and his and Foucault’s work on the Marquis de Sade; Edward Said; and the Structuralist Controversy conference and Eugenio Donato). I also spoke about that work in Oxford in June, and the audio recording of my talk is here. Others connect much more directly to the Indo-European work, such as a piece on Gillian Rose and the Indo-Europeanists, on Benveniste’s work on auxiliary verbs, and on the book series in which translations of Benveniste and André Martinet appeared. I wrote pieces on connected but not central figures in the story I’m telling – on Hermann Lommel and the ancient Aryans and Lucien Gerschel and Dumézil’s readings of the story of Coriolanus – and updated a piece on Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Fondation Loubat lectures, who might yet play a more significant role.

Roman Jakobson is an important figure in the careers of many of the people I’m discussing in this project, and I wrote a short piece about his work for Franz Boas on the Paleo-Siberian and Aleutian material at the New York Public Library, based on the archival sources. I gave a short talk on Jakobson to my department in late June, and hope to develop that into something more substantial, and have another piece on Jakobson’s 1972 Collège de France courses nearly ready.

Future ‘Sunday Histories’ will look at some more themes relating to the Indo-European project, though the intention is not to share draft material from the developing manuscript, but rather connected discussions. I have also have some pieces in development which are not connected to this work including on the biologist Étienne Wolff, on the Glyph journal, and on Foucault’s early English translations [now available here].

Previous updates on this project can be found here, along with links to some research resources and forthcoming publications. The re-edition of Georges Dumézil’s Mitra-Varuna is available open access. There is a lot more about the earlier Foucault work here. The final volume of the series is The Archaeology of Foucault, and the special issue of Theory, Culture & Society I co-edited on “Foucault before the Collège de France” has some important contributions on the earlier parts of Foucault’s career, with some pieces free to access. My recent articles include “Foucault, Dynastics and Power Relations” in Philosophy, Politics and Critique and “Foucault and Dumézil on Antiquity” in Journal of the History of Ideas (both require subscription, so ask if you’d like a copy); and “Alexandre Koyré and the Collège de France” in History of European Ideas (open access).

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 30 – archive work in Paris, Bern and Cambridge, MA, and Benveniste’s library | Progressive Geographies