Jacques Derrida was certainly a careful reader of Émile Benveniste. He wrote a critique of Benveniste in “Le supplément de copule. La philosophie devant la linguistique” which appeared in 1971, in a special issue of Langages, “Épistémologie de la linguistique” edited by Julia Kristeva in tribute to Benveniste. The essay was collected in Marges de la philosophie and translated as “The Supplement of Copula: Philosophy before Linguistics” in Margins of Philosophy. Derrida often makes use of Benveniste’s Vocabulaire des institutions indo-européennes, the Dictionary of Indo-European Concepts and Society, in his later work, of which the discussion of the gift in Given Time, or of hospitality in his lectures are the best-known examples. A marked up copy of the original English translation is in Derrida’s library now held by Princeton University. There are lots more references, as the posthumous seminars make clear. In these seminars he often voices criticisms, while nonetheless often building on Benveniste’s analyses. This side of the relation is well attested and Étienne Balibar, in particular, has written about it. Much more could be said of the seminars and Derrida’s reading of Benveniste but that is not my concern here.

But was Benveniste a reader of Derrida? There is a tragic terminus ante quem – Benveniste’s incapacitating stroke of December 1969, after which he spent nearly seven years in hospitals and care homes before his death, suffering from aphasia and partial paralysis. So, he would not have been able to respond to “Le supplément de copule”, or know of the use Derrida made of his Vocabulaire, which was published shortly before his stroke.

Benveniste certainly knew people who knew Derrida – Kristeva and Roland Barthes, or Tzvetan Todorov. There were undoubtedly opportunities for Benveniste to be aware of Derrida’s work, even from quite early. Any reading of Derrida would have happened at the beginning of Derrida’s career, before or around the time of his miraculous year of 1967, when the books Of Grammatology, Writing and Difference and Speech and Phenomena all appeared. Although Derrida had published before then, notably his long introduction to his translation of Husserl’s The Origin of Geometry in 1962, and these three books all make use of previously published material, 1967 is when he really burst onto the scene. Or we could push the date back a little to the 18-21 October 1966 Baltimore conference on structuralism at which he gave the closing talk, “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences” (reprinted in Writing and Difference). I write about that event, and share a link to its recently rediscovered recordings, here.

In his “Translator’s Introduction” to Benveniste’s Last Lectures, delivered in 1968-69, John E. Joseph says this of the part of the course on writing:

He might have talked about how his approach did or did not articulate with Derrida’s, whose Of Grammatology we know that he read, since his manuscripts include notes taken during his reading of it. Irène Fenoglio explains his silence by Benveniste’s desire to treat the subject as a linguist, hence ignoring someone he regarded as a philosopher – which is entirely plausible, and in line with what we know about the operation of disciplinary boundaries at the time. Derrida always spoke of how much Benveniste’s etymological enquiries enriched his thinking, and his writings show that it is so. Here was a lost opportunity to repay the debt (p. 48).

Joseph repeats this claim in a chapter, stressing that “Benveniste’s reading notes mention specific passages of the book” (“L’hostipalité des linguistes”, p. 320 n. 4). Irène Fenoglio is one of the editors of Benveniste’s course, and Joseph’s reference is to her chapter “L’écriture au fondement d’une ‘civilisation ‘laïque’”, published in Autour d’Émile Benveniste, pp. 168-69, and in particular the discussion on pp. 231-32.

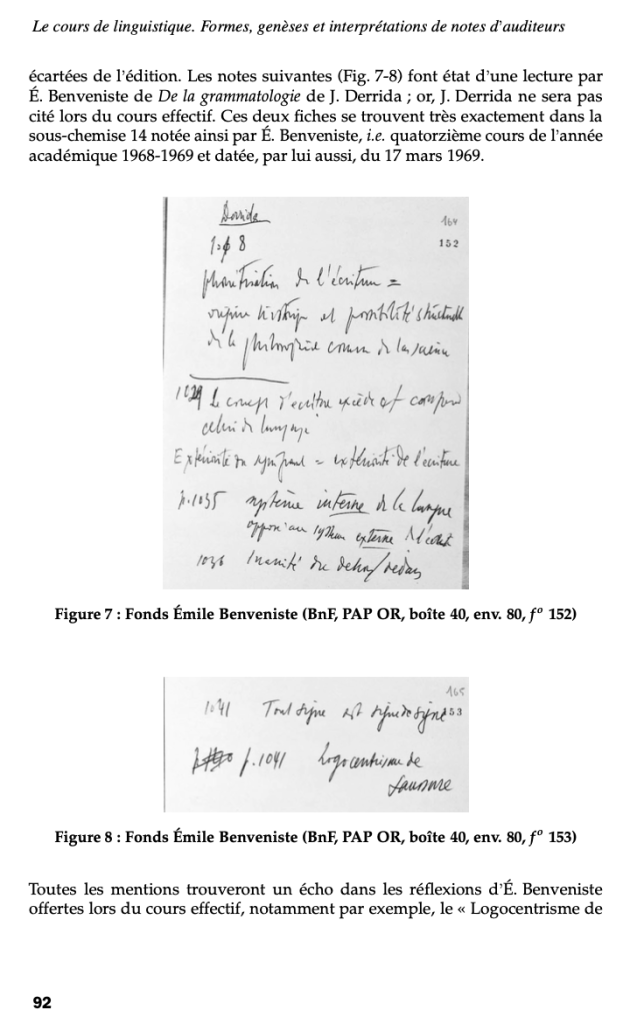

In another one of her articles, “Éditer un cours de linguistique générale à partir d’archives manuscrites”, Fenoglio says these notes “refer to E. Benveniste’s reading of Derrida’s De la grammatologie” (p. 92) The notes which prove this, she claims, are found in the subfolder of the 14th lecture of the course, dated to 17 March 1969. She indicates that this is important even if “Derrida is not cited in the actual lecture” (p. 92). Fenoglio reproduces those pages in her chapter, p. 169, and her article, p. 92. I have learned a great deal from Fenoglio and Joseph’s work – he is the author of a magisterial biography of Saussure, for example, and Fenoglio has edited and interpreted various texts from Benveniste’s archives (see also her “Le fonds Émile Benveniste de la BnF est-il prototypique?”). But on this point about Benveniste reading Derrida’s book, I’m not sure.

The materials relating to the 1968-69 course are in box 40 of the Papiers d’orientalistes at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. I’ve seen the notes mentioned by Joseph and Fenoglio in the original, folios 152 and 153, rather than just Fenoglio’s reproduction, and they are certainly about Derrida and logocentrism. There is unfortunately not much to see. There are nine lines of writing on one page and two lines at the top of the second. The reproduction Fenoglio provides – which can be seen above, and in more detail online, figures 7 and 8 – is complete, though the blank bottom of the second page is not shown.

These notes are not however about Derrida’s De la grammatologie, the book published in 1967. They are about an earlier version of one small part of that book, an article previously published in Critique in 1965, “De la grammatologie”, not De la grammatologie. The notes are not completely clear, but in the left margin there are a series of numbers – 1018, 1029, 1035, 1036, 1041, 1041. Only two of these have a ‘p.’ before them; two are written over to correct an earlier mistake, one is crossed out and rewritten. But they are page numbers, and they accord well to the content of the first part of the article, published on pages 1016-42 of issue 223 of the journal in 1965. This is not the complete piece, which was split across two issues, presumably because of its length: part I in 1965; part II in 1966, pages 23-53 of the issue 224. All the page references in Benveniste’s notes are to the first part, from 1965.

So, Benveniste quotes Derrida’s “la phonétisation de l’écriture – origine historique et possibilité structurelle de le philosophie comme de la science” from p. 1018; notes the distinction between the internal system of language and the external, which Derrida is relating to Saussure (p. 1035), and the complication of the inside and outside (p. 1036). He also indicates Derrida’s claim about the “logocentrism” of Saussure (p. 1041).

But both Joseph and Fenoglio say that these notes prove Benveniste read De la grammatologie, the book. It matters, because that text accomplishes much more than just what is said in the article, especially if Benveniste only read its first part.

Derrida’s two-part article discusses three works – Madeleine V. David, Le débat sur les écritures et l’hiéroglyphe aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, published in 1965; André Leroi-Gourhan, Le Geste et la parole, published in two volumes in 1964 and 1965, with the first volume subtitled Technique et Langage; and a proceedings, L’écriture et la psychologie des peuples, published in 1963 from a conference organised by the Centre International de Synthèse in May 1960.

The books indicate a wide network of ideas. David’s book was initially a thesis at the École Pratique des Hautes Études under the supervision of Ignace Meyerson, with Alexis Rygaloff and Jean-Pierre Vernant the rapporteurs and Fernand Braudel, director of the sixth section of the EPHE, thanked for his support of its publication (pp. 9-10). Leroi-Gourhan was a former student of Marcel Mauss, his work was important to writings by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari and Bernard Stiegler among others, and he was appointed to the Collège de France in 1969 in a chair of prehistory made possible by Georges Dumézil’s retirement the previous year. The participants in L’écriture et la psychologie des peuples connect in multiple ways to Benveniste’s career – the ancient Greek philologist Pierre Chantraine had been a student of Antoine Meillet alongside Benveniste, and like the sociologist of Islam Maxime Rodinson was a colleague of Benveniste at the École Pratique des Hautes Études. The Hittite scholar Emmanuel Laroche taught at the EPHE too, and was effectively Benveniste’s successor at the Collège de France, appointed in 1972; Marcel Cohen was a colleague at the EPHE, and the Assyriologist René Labat and the Tibetan scholar Jean Filliozat were colleagues at the Collège. Alexandre Koyré took part in some of the discussions of papers. Less surprising than Benveniste’s interest in a review of this collection was that he was not involved in the conference himself.

Derrida’s two-part article provides material which is developed into part one of De la grammatologie, “L’écriture avant la lettre”, “Writing before the Letter”. Of course, even in the first part of the article Derrida goes beyond the books under discussion, and anticipates many themes of his wider work, including Heidegger, the metaphysics of presence, Saussure, and the relation between speech and writing.

A further page of notes by Benveniste, folio 171 in the same box of the Papiers d’orientalistes, are notes on “Grammatologie”. Derrida is not mentioned by name, and while some of its vocabulary is similar, it’s worth noting that ‘grammatology’ is not exclusive to Derrida. As far as I’m aware, its first use is in Ignace Gelb’s A Study of Writing: The Foundations of Grammatology, the first edition of which appeared in 1952. Later editions remove the word ‘grammatology’ from the subtitle. Derrida’s interpretation arguably makes the term his own. The same can be said of the term ‘logocentrism’, coined by Ludwig Klages but usually associated with Derrida. The last note by Benveniste on this article reproduced by Fenoglio mentions “logocentrisme de Saussure”, referencing p. 1041 of Derrida’s article.

All the discussion of Claude Lévi-Strauss in De la grammatologie comes in the second part of the book, almost twice the length of the first. Rousseau in mentioned in the article in a few places (pp. 1017, 1030, 1037-38, 1039 n. 19), but the more substantial discussion also comes in the second part of the book. In an interview with Dawn McCance, the philosopher and literary theorist Rodolphe Gasché recalls that:

On one occasion at least, and with some amusement, Derrida pointed out to me that the book, Of Grammatology, that made him famous was… a work patched together of two unrelated pieces: on the one hand, a reworked review article on several important books on writing that had just been published, and which appeared in Critique in 1965 and 1966 under the title “De la Grammatologie”; and, on the other hand, his lectures during this same academic year at the École normale supérieure (ENS) on Rousseau, that is, on a subject that was not one of his own choice, but which was determined by the fact that Rousseau, that very year, was on the program of the “aggregation,” and which it was thus his duty to teach in order to prepare the normaliens for this competitive examination for the recruitment of high school teachers and university professors (“Crossings: An Interview with Rodolphe Gasché”, p. 202).

None of this means that Benveniste did not read the second part of the article, or the 1967 book De la grammatologie. As Fenoglio notes, his library was sold after his death to the Linguistics Institute at the University of Bern, where his literary executor Georges Redard taught. Fenoglio says that she has seen a copy in that library which comes from the Benveniste collection (Fenoglio, “L’écriture au fondement d’une ‘civilisation ‘laïque’”, p. 159 n. 1). That copy was not there when I visited the Bibliothek Sprachwissenschaft – the book with the shelfmark she gives was the 1974 printing of the text, not the 1967 original (LA 042). There is unfortunately not a comprehensive list of the original deposit available. There may be other notes by Benveniste on Derrida elsewhere in his papers, though I have looked at everything at least once. Of course, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

However, the surviving notes taken by Benveniste on Derrida do not prove he read the book De la grammatologie. He certainly read the earlier article “De la grammatologie”, but seemingly only part one of that two-part piece. As a review of work on writing, Derrida’s essay was something which would have undoubtedly interested Benveniste for the course he was teaching. Several themes of his wider work are previewed here, but Derrida’s essay is not the major work of which it would become a part. I think it’s more likely that Benveniste simply took this as a review essay about writing which was quite interesting for his research and teaching, not as a text by a philosopher which he, as a linguist, could chose to engage with or to ignore. At other times he was certainly willing to engage with philosophy or other material outside of linguistics.

If it was a “lost opportunity” for Benveniste not to have lectured or written about Derrida, I think it was even more of a missed prospect that he had seemingly read so little of his work.

References

L’écriture et la psychologie des peuples: XXIIe semaine de synthèse, Paris: Librarie Armand Colin, 1963.

Étienne Balibar, “De la certitude sensible à la loi du genre”, Citoyen sujet et autres essais d’anthropologie philosophique, Paris: PUF, 2011, 183-206; “From Sense Certainty to the Law of Genre: Hegel, Benveniste, Derrida”, Citizen Subject: Foundations for Philosophical Anthropology, trans. Stephen Miller, New York: Fordham University Press, 2016, 106-20.

Émile Benveniste, Dernières Leçons: Collège de France 1968 et 1969, eds. Jean-Claude Coquet and Irène Fenoglio, Paris: EHESS/Gallimard/Seuil, 2012; Last Lectures: Collège de France 1968 and 1969, trans. John E. Joseph, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019.

Madeleine V. David, Le Débat sur les écritures et l’hiéroglyphe aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles et l’application de la notion de déchiffrement aux écritures mortes, Paris: SEVPEN, 1965.

Jacques Derrida, “De la grammatologie”, Critique 223, 1965, 1016-42, and Critique 224, 1966, 23-53.

Jacques Derrida, De la grammatologie, Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1967; Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Spivak, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976.

Jacques Derrida, “Le supplément de copule: La philosophie devant la linguistique”, Langages 24, 1971, 14-39; reprinted in Marges – de la philosophie, Paris: Minuit, 1972, 209-46; “The Supplement of Copula: Philosophy before Linguistics”, Margins of Philosophy, trans. Alan Bass, Brighton: Harvester Press, 1982, 175-205.

Irène Fenoglio, “Le fonds Émile Benveniste de la BnF est-il prototypique? Réflexions théoriques et méthodologiques sur les potentialités d’exploitation d’archives linguistiques” in Valentina Chepiga and Estanislao Sofia eds. Archives et manuscrits de linguistes, Louvain-la-neuve: Academia-L’Harmattan, 2014, 11-46.

Irène Fenoglio, “L’écriture au fondement d’une ‘civilisation ‘laïque’”, in Autour d’Émile Benveniste, Paris: Seuil, 2016, 153–236.

Irène Fenoglio, “Éditer un cours de linguistique générale à partir d’archives manuscrites: Essai de méthodologie critique”, Langages 209, 2018, 77-96.

I.J. Gelb, A Study of Writing: The Foundations of Grammatology, Chicago: University of Chicago Press/London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1952.

John E. Joseph, Saussure, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

John E. Joseph, “Translator’s Introduction” in Émile Benveniste, Last Lectures: Collège de France 1968 and 1969, eds. Jean-Claude Coquet and Irène Fenoglio, trans. John E. Joseph, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019, 31-60.

John E. Joseph, “L’hostipalité des linguistes: Puech coincé entre Benveniste et Derrida”, in Valentina Bisconti, Anamaria Curea and Rossana de Angelis eds. Héritages, receptions, écoles en sciences du langage: avant et après Saussure, Paris: Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2019, 315-23.

André Leroi-Gourhan, Le Geste et la parole, Paris: Albin Michel, two volumes, 1964-65; Gesture and Speech, trans. Anna Bostock Berger, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993.

Dawn McCance, “Crossings: An Interview with Rodolphe Gasché”, Mosaic 50 (1), 2017, 201-26.

Archives and book collections

Papiers d’orientalistes, Emile Benveniste, Bibliothèque rationale de France, box 40, Collège de France. Cours 1968-1969: Problèmes de linguistique générale, https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc1265929?collect

The Library of Jacques Derrida, Firestone Library, Princeton University

Émile Benveniste library, Bibliothek Sprachwissenschaft, Universität Bern

This is the 41st post of a weekly series, where I post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome. A few shorter pieces in a similar style have been posted mid-week.

The full chronological list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here, with a thematic ordering here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 30 – archive work in Paris, Bern and Cambridge, MA, and Benveniste’s library | Progressive Geographies