Joseph Falaky Nagy generously reviews the new edition of Georges Dumézil, Mitra-Varuna: An Essay on Two Indo-European Representations of Sovereignty, trans. Derek Coltman, ed. Stuart Elden, from Hau Books in Journal of Folklore Research Reviews.

Both the journal and the book are available open access. Here’s a passage from the review about my editorial work:

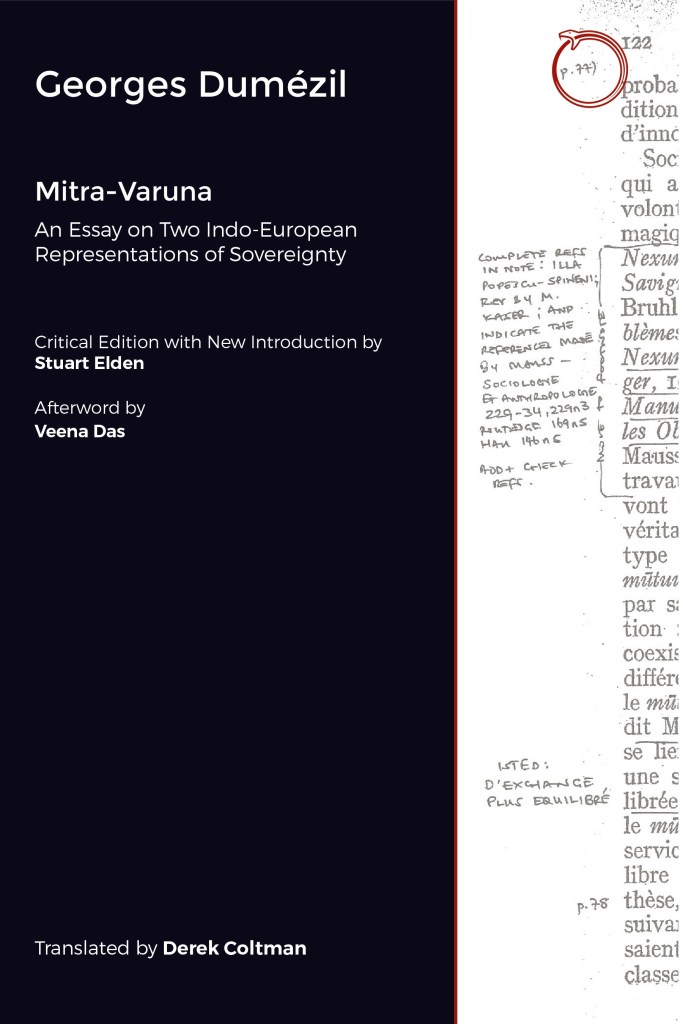

Even an owner of the second edition of Mitra-Varuna in French, or of the 1988 Zone Books edition of the translation by Derek Coltman, which forms the basis of the present book, would find much of additional value in the publication under review. (Stuart Elden, responsible for this slightly revised version of Coltman’s translation, points out that the Zone Books publication, like virtually all of the English translations of Dumézil’s work published over the past several decades, is out of print [p. xxiv].) As the cover of this book, brought out by Hau Books of Chicago, vividly shows, much of Dumézil’s revision of Mitra-Varuna evolved in the tiny notes he entered by hand into the margins of the printed first edition. Elden’s editorial work makes it possible for the reader to find the major changes between the two French editions, and to consult the more important original passages, mostly presented in both French and English translation, that have undergone substantial change. Helpfully, Elden has also clarified or corrected Dumézil’s sometimes telegraphic bibliographical references.

Adding substantially to the value of this publication is Elden’s introductory essay, not just a preparation of the reader for Mitra-Varuna but more generally, as he titles it, a “Re-Introduction to Georges Dumézil”: a much-needed reminder to the modern scholarly world of the numerous contributions that Dumézil made to the fields of comparative mythology, particularly in regard to the Indo-European world, and to the study of the languages and the oral traditions of the peoples of the Caucasus. (It is in the last of these fields, perhaps the closest to Dumézil’s heart, that his folkloristic instincts were most evident.) Elden’s outline of Dumézil’s life, scholarly career, and achievements includes an account of the major influences on his work, emanating from other great scholars of the last century, such as the historian Granet and the sociologist Mauss. There is also a very judicious account of the controversial accusation that Nazi or fascist sympathies underlay Dumézil’s scholarship published in the period leading up to the Second World War, in particular his Mythes et dieux des Germains (1939). Dumézil’s reputation and posterity were damaged by this controversy in his later years and after his death in 1986. But was this an instance of guilt by association, which had less to do with anything Dumézil said or did, and more with the affiliations of some predecessors and colleagues whose work Dumézil utilized, or with epigones gone astray, who in later times took the very concept of “Indo-European” (a fundamentally linguistic and definitely not an ethnic or racial category) and even some of Dumézil’s own ideas, in nefarious directions? Elden grapples with this question fairly and insightfully.

But I should note that the cover image is a page of my marked up photocopy of the first edition, comparing the two French editions, not Dumézil’s own annotations.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.