Clémence Ramnoux (1905-1997) was an important French scholar of ancient Greece. She worked mostly on the pre-Socratics, especially Heraclitus. Alongside Simone Pétrement she was one of the first two women who entered the philosophy programme of the École Normale Supérieure in 1927. Simone Weil would join them the year after. As Penelope Deutscher discusses, for her whole career she faced institutional challenges because of the marginalised position of women in the French academy. In French classical studies, Ramnoux was a pioneer, a little older than Jacqueline de Romilly (1913-2010), who also worked on classical Greece, particularly on Thucydides. De Romilly was the first woman to hold a chair at the Collège de France, and the second woman elected to the Académie française (after Marguerite Yourcenar). Deutscher says that Ramnoux’s contribution and originality has been repeatedly marginalised, and indicates how, even at the 1998 memorial conference, “the forgetting of Ramnoux was staged right there at her own commemorative homage” (“‘Imperfect Discretion’”, p. 162).

Ramnoux knew Foucault, attending the 1965 Colloque du Royaumont conference on Nietzsche, organised by Gilles Deleuze and Martial Gueroult, and the Saclay conference on structuralism in 1970 (which I briefly mention here and will discuss in more detail in a future piece). After Foucault’s “Nietzsche, Freud, Marx” lecture at the first of these conferences, she took part in the discussion, though Foucault says he has little to add to her indication of the link Lou Salomé made between Nietzsche and Freud (Dits et écrits, Vol I, pp. 577-78). Foucault knew at least her book on Heraclitus, with some notes in the Fonds Michel Foucault (NAF28730, box 32, folder 1). The recently catalogued library of Foucault’s apartment indicates that she gave him an offprint of her 1965 article on “«Les fragments d’un Empédocle» de Fr. Nietzsche”, with a dedication. This is a very interesting discussion of an early abandoned project by Nietzsche. It was planned around the time of his incomplete book Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, the surviving text of which does not cover Empedocles, although the plan was that it would.

Importantly for my current work on Indo-European thought in France, Ramnoux was a former student of Georges Dumézil. She dates her first reading of Dumézil to the Occupation, and says she attended his courses at the École Pratique des Hautes Études from 1944. An attendance list suggests she continued to attend at least as late as 1953 (Fonds Georges Dumézil, box 73, folder 7). Ramnoux’s explicit references to Dumézil are limited, but she described him as her “first master” (Œuvres, Vol II, 289). Her essay “Ce que je dois à Georges Dumézil ou de la légende à la sagesse” appeared in the 1981 collection Hommages à Georges Dumézil, and was reprinted in her collection Études présocratiques II, which is included in the second volume of Œuvres (Vol II, pp. 493-512). There she discusses Dumézil’s impact on her work, alongside Lévi-Strauss’s work on myth and her parallel training in psychoanalysis. Dumézil’s focus on Rome, India and Iran (and, we might add, the Caucasus) informed her work on Greece, as it also did for Jean-Pierre Vernant and Marcel Detienne, among others. She says she gained from Dumézil a “knowledge, undoubtedly, of the archaic religions of Europe, but rather more than that: I owe to him an art of reading and deciphering” (p. 512).

I’ve previously mentioned an interesting collection Clémence Ramnoux, entre mythes et philosophie: Dumézil, Freud, Bachelard (avec des inédits de Clémence Ramnoux), edited by Rossella Saetta Cottone, which came out in October 2025. Saetta Cottone’s editorial work for this book is useful, as is her introduction to the two volume Ramnoux, Œuvres. There is a webpage about the project of reassessing Ramnoux’s work here – a collaboration between Saetta Cottone and Luan Reboredo.

The website stresses Ramnoux’s connections to philosophers including Jean Wahl, Pierre-Maxime Schuhl and Gaston Bachelard, as well as classicists such as Vernant and André-Jean Festugière, and international names such as Harold Cherniss. Maurice Blanchot wrote the preface to her Heraclitus book; Wahl to the first volume of her Études présocratiques. Cottone and Reboredo’s site indicates several other possible connections, some of which are explored in the recent collection. This would include her friendship with Pierre Bourdieu in Algeria (see Collard, “Clémence Ramnoux et Pierre Bourdieu”), her time at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, and her work in founding the philosophy department at Université de Paris X Nanterre with Paul Ricœur and Jean-François Lyotard (see Courrier, “L’enseignement de Clémence Ramnoux à Nanterre”).

This site also indicates that Ramnoux’s archive is now at the École Normale Supérieure. There is a useful guide to relevant archives in Clémence Ramnoux, entre mythes et philosophie, 313-15. This says where, for example, to find her letters to Bourdieu, Henri Gouhier, Jean Hyppolite, Jacques Maritain and Wahl, and the geographer Jean Gottmann, and the record of her career at the Archives Nationales. These seem like interesting things to explore. One mistake here though: her archives concerning visiting posts at the IAS are in its own archives, not at Princeton University.

The IAS archives have some correspondence and other documents concerning her visits there for the 1955-56 academic year and the first term of 1960-61. These include letters to the director Robert Oppenheimer, from Cherniss, who was instrumental in her invitation, the cultural advisor to the French ambassador, Edouard Morot-Sir, and about the Fulbright travel grant to support her visits. On her first visit there she worked on Héraclite, ou l’homme entre les choses et les mots, later submitted as her major doctoral thesis; on the second visit she wrote Mythologie, ou la Famille olympienne, published in 1962, and worked on the fragments of Empedocles. It seems she intended to do a more extensive study of Empedocles. She also worked on some translations of Heraclitus, for a small, very limited edition, with illustrations by the sculptor Étienne Hajdú. She later presented a copy to the IAS library.

An interview with Raymond Bellour gives some sense of her intellectual formation, and in particular the importance of G.S. Kirk’s study and Cherniss’s IAS seminar on Heraclitus for her analysis. “I worked with the edition of Diels in the middle, Kirk’s book on the right, the manuscript notes of Cherniss to the left, step by step and fragment by fragment” (Œuvres Vol II, 648). Despite this, Ramnoux’s work can also be a good example of the failed conversation between French classicists and anglophone ones. Herbert Jennings Rose, who had an ongoing feud with Dumézil, among others, wrote a bad-tempered assessment of La nuit et les enfants de la nuit dans la tradition grecque for The Classical Review in 1961.

One of Ramnoux’s earliest essays was published in the first issue of La Psychanalyse, an issue which included Émile Benveniste’s essay on language in Freud’s work, Hyppolite’s discussion of Freud with Jacques Lacan’s introduction and commentary, Lacan’s 1953 lecture known as the Rome discourse, Lacan’s translation of Martin Heidegger’s “Logos” essay, and texts by Hyppolite and Daniel Lagache, among others. The issue had the cover title “Sur la Parole et le Langage”, and the inside cover “De l’usage de la parole et des structures de langage dans la conduit et dans le champ de la psychanalyse”. Lacan’s Rome essay is reprinted in Écrits, as Chapter 12. Ramnoux’s essay was “Hadès et le psychanalyse”, which is reprinted in the first volume of her Études présocratiques, included in Œuvres. She would publish at least one more essay in that journal, “Sur une page de Moïse et le Monothéisme” in 1957, on Freud’s controversial late book Moses and Monotheism.

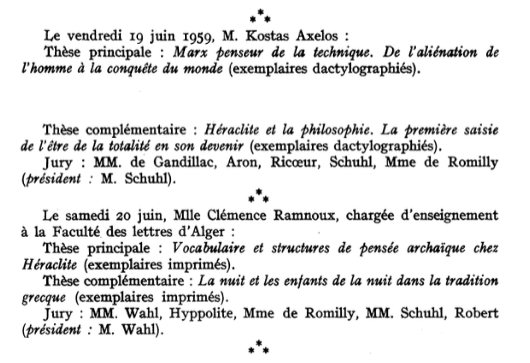

Somewhat strangely, given their shared interests, Ramnoux does not seem to mention the work of Kostas Axelos, and I don’t think he makes reference to her work. Ramnoux’s Héraclite, ou l’homme entre les choses et les mots dates from 1959; Axelos’s Héraclite et la philosophie to 1962. Both are briefly mentioned in G.B. Kerferd’s 1965 survey of “Recent Work on Presocratic Philosophy”. Interestingly, Axelos defended his theses for the doctorat d’état on 19 June 1959, with Marx penseur de la technique as the primary thesis; Héraclite as the secondary; and Ramnoux defended the next day. Axelos’s edition of Heraclitus, with Greek text and facing page French translation, had been published in 1958. I suspect there is more to the story, since they must have been aware of each other’s work, but I don’t know what that story might be. The Axelos-Ramnoux relation may have been clouded by Axelos’s Heideggerian approach. As Monique Dixsaut says, Ramnoux “refers briefly to Heidegger, but always to approve or reject his translation of a word, and never to his conception of being and time” (Préface, 16). However, Jean Wahl’s preface to her Études présocratiques suggests Heidegger, “was no stranger to the evolution of her thought, and behind him Nietzsche” (Œuvres Vol II, 11). There are indeed a few mentions of his work across hers, and in the interview with Bellour she discusses reading him but denies too close an influence (Œuvres Vol II, 649). But Axelos seems entirely absent from her work.

Ramnoux’s primary thesis was Vocabulaire et structures de pensée archaïque chez Héraclite, the secondary or complementary thesis was La nuit et les enfants de la nuit dans la tradition grecque. Vocabulaire et structures was retitled Héraclite ou l’homme entre les choses et les mots when it was published; the secondary thesis kept the same title. Both are reprinted in Œuvres, Volume I. Wahl, Hyppolite, de Romilly, Schuhl and someone I assume was Louis Robert were the examining jury. De Romilly and Schuhl were also on Axelos’s jury, along with Maurice de Gandillac, Raymond Aron, and Paul Ricoeur (“Nouvelles philosophiques”, 1959). Formidable lineups for both, and it is worth stressing the scale of what was required for a doctorat d’état: the secondary thesis for both Axelos and Ramnoux was a full-length book, and Axelos had published his bi-lingual edition of Heraclitus while working on his theses.

In Clémence Ramnoux, entre mythes et philosophie, Reboredo provides some supplementary texts – three short radio broadcasts, a couple of unpublished conference papers, and three articles which were not included in Œuvres. The conference papers are the first posthumous publications of Ramnoux’s work. Œuvres comprises most of her work – the bibliography in the new collection indicates that the main omissions are pre-1954 writings, some of her articles, and her book reviews. A striking aspect of Ramnoux’s career is the number of interesting articles she published before the submission of her theses. She also wrote about, among other themes, Parmenides, King Lear, Hegel, Bachelard and the Finn (or Fenian) cycle.

I’m aware much of this initial piece is about her connections to others, mostly men, and not so much about her work in itself, but it hopefully serves as an introduction to some of her interests and where she might be situated in a wider network of ideas. As far as I know, none of her work is translated into English.

References

“Nouvelles philosophiques”, Les Études philosophiques 14 (3), 1959, 405-12.

Les Fragments d’Héraclite d’Éphèse, ed. and trans. Kostas Axelos, Paris, 1958.

Hommages à Georges Dumézil, Aix-en-Provenance: Pandora, 1981.

Textes d’Héraclite, trans. Clémence Ramnoux, illustrations by Étienne Hajdu, Paris: Aux dépens de l’artiste, 1965.

Kostas Axelos, Héraclite et la philosophie, Paris: Minuit, 1962.

Victor Collard, “Clémence Ramnoux et Pierre Bourdieu: Deux générations de normaliens philosophes découvrant la sociologie en Algérie (1958-1960)”, in Rossella Saetta Cottone ed. Clémence Ramnoux, entre mythes et philosophie: Dumézil, Freud, Bachelard (avec des inédits de Clémence Ramnoux), Paris: Éditions Rue d’Ulm, 2025, 51-83.

Yves Courrier with Guy Basset and Paul Lionnet, “L’enseignement de Clémence Ramnoux à Nanterre (1965-1975): Un témoinage et un hommage”, in Rossella Saetta Cottone ed. Clémence Ramnoux, entre mythes et philosophie: Dumézil, Freud, Bachelard (avec des inédits de Clémence Ramnoux), Paris: Éditions Rue d’Ulm, 2025, 109-23.

Penelope Deutscher, “‘Imperfect Discretion’: Interventions into the History of Philosophy by Twentieth-Century French Women Philosophers”, Hypatia 15 (2), 2000, 160-80.

Monique Dixsaut, “Préface”, in Rossella Saetta Cottone ed. Clémence Ramnoux, entre mythes et philosophie: Dumézil, Freud, Bachelard (avec des inédits de Clémence Ramnoux), Paris: Éditions Rue d’Ulm, 2025, 9-19.

Michel Foucault, Dits et écrits, eds. Daniel Defert and François Ewald, Paris: Gallimard, four volumes, 1994.

Sigmund Freud, Der Mann Moses und die monotheistische Religion: Drei Abhandlungen, Amsterdam: Albert de Lange, 1939; Moses and Monotheism: Three Essays, trans. James Strachey, in The Origins of Religion: Totem and Taboo, Moses and Monotheism and Other Works – Penguin Freud Library Volume 13, London: Penguin, 1990.

G.B. Kerferd, “Recent Work on Presocratic Philosophy”, American Philosophical Quarterly 2 (2), 1965, 130-40.

G.S. Kirk, Heraclitus The Cosmic Fragments: A Critical Study, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1962 [1954].

Friedrich Nietzsche, Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, trans. Marianne Cowan, Washington, D.C., 1962.

Clémence Ramnoux, “Mythes et métaphysique”, Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale 55 (4), 1950, 408-31.

Clémence Ramnoux, “Hadès et le psychanalyse” (1953), reprinted in Études présocratiques, and in Œuvres, Vol II, 215-28.

Clémence Ramnoux, “Sur une page de Moïse et le Monothéisme”, reprinted in Études présocratiques, and in Œuvres, Vol II, 229-47.

Clémence Ramnoux, La nuit et les enfants de la nuit dans la tradition grecque, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1959; reprinted in Ramnoux, Œuvres, Vol I, 5-179.

Clémence Ramnoux, Héraclite ou l’homme entre les choses et les mots, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 1968 [1959]; reprinted in Ramnoux, Œuvres, Vol I, 179-617.

Clémence Ramnoux, Mythologie, ou la Famille olympienne, París, Armand Colin, 1962; reprinted in Ramnoux, Œuvres, Vol I, 619-772.

Clémence Ramnoux, “«Les fragments d’un Empédocle» de Fr. Nietzsche”, Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale 70 (2), 1965, 199-212; reprinted in Études présocratiques, and in Œuvres, Vol II, 123-37.

Clémence Ramnoux, “Entretien avec Clémence Ramnoux”, in Raymond Bellour, Le Livre des autres: Entretiens, Paris: Union Générale d’Éditions 10/18, 1978, 157-80, reprinted as “Entrétien sur Héraclite” in Œuvres, Vol II, 645-56.

Clémence Ramnoux, “Ce que je dois à Georges Dumézil ou de la légende à la sagesse”, Hommages à Georges Dumézil, Aix-en-Provenance: Pandora, 1981, 101-20; reprinted in Ramnoux, Œuvres, Vol II, 493-512.

Clémence Ramnoux, Œuvres, ed. Alexandre Marcinkowski, Paris: Les Belles Lettres, two volumes, 2020.

H.J. Rose, “Symbolism in Greece?” The Classical Review 11 (1), 1961, 77-79.

Rossella Saetta Cottone, “Présentation: Clémence Ramnoux entre les choses et les mots”, in Clémence Ramnoux, Œuvres, ed. Alexandre Marcinkowski, Paris: Les Belles Lettres, two volumes, 2020, Vol I, xv-xxviii.

Rossella Saetta Cottone and Luan Reboredo, “Clémence Ramnoux : la pensée archaïque à la croisée des sciences de l’Antiquité et des sciences humaines”, https://sciences-antiquite.sorbonne-universite.fr/actualites-isantiq/clemence-ramnoux-la-pensee-archaique-la-croisee-des-sciences-de-lantiquite-et, 31 January 2023, updated 4 June 2025.

Rossella Saetta Cottone ed. Clémence Ramnoux, entre mythes et philosophie: Dumézil, Freud, Bachelard (avec des inédits de Clémence Ramnoux), Paris: Éditions Rue d’Ulm, 2025.

Archives

Fonds Georges Dumézil, DMZ, Collège de France

Fonds Michel Foucault, NAF 28730, Bibliothèque nationale de France

La bibliothèque de M. Foucault et de D. Defert (catalogue), https://heurist.huma-num.fr/heurist/ffl_1/web/11963/11957/?lang=ENG

Director’s Office files, Shelby White and Leon Levy Archives Center, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Caitlin Rizzo for providing material from the IAS archives.

This is the 54th post of a weekly series, posted every Sunday throughout 2025, and now entering a second year. The posts are short essays with indications of further reading and sources. They are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally, but are hopefully worthwhile as short sketches of histories and ideas. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare parts, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome. A few, usually shorter, pieces in a similar style have been posted mid-week. I’m not sure I’ll keep to a weekly rhythm in 2026, but there will be at least a few more pieces.

The full chronological list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here, with a thematic ordering here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

returning to Virilo’s interview in Pure War and thanks to your blog now have some context for his use of Dumezil in his move against sociology and into mythology.

Thanks – glad it’s useful. I should go back to Virilio to check this reference.

2 The Time of War, starts like:

Lotringer: You reject sociological analysis, but in its place you put a

mythological model, the structure of the three ”functions” ( sacred,

military, and economic) established by Georges Dumezil through the

collective representations of Indo-European society. Indo-European

tripartition is a mythical projection more than a historical reality. What

allows us to accord it an analytical capacity greater than that of

contemporary sociology?

Virilio: Myths have an analytical capacity that cannot be denied. By

comparison sociology seems a surface effect. What interests me is

tendency. As Churchill wrote: “In ancient warfare, the episodes were

more important than the tendencies; in modem warfare, the tendencies are

more important than the episodes.” Myth is tendency. The three functions

thus seem to me analyzers of the knowledge of war, political knowledge,

achieving infinitely more than all the successive sociological macro- or

micro- developments. Of course a tendency is not a reality, it’s a statistical

vision. The myth as analyzer and as tendency is itself also of a statistical

order”

goes on from there…

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 31 – Paris archives, library problems, and working towards a complete draft | Progressive Geographies