Two small things I’ve found or noticed recently which shed a little light on Foucault’s engagement with his critics.

1. Jacques Derrida

I have discussed the Derrida-Foucault debate about Foucault’s History of Madness before, most fully in The Archaeology of Foucault (pp. 16-21). I’m not going to repeat that or provide all the references again here. Essentially, Derrida gave a lecture on the book in 1963, “Cogito et histoire de la folie”, which Foucault attended, and Derrida published his critique in the Revue de métaphysique et morale later that same year. Derrida reprinted the text in his book L’Écriture et la différence in 1967, which is translated as Writing and Difference. Foucault eventually responded, first in a text for a Japanese audience, in part because they were going to include Derrida’s text in a journal section on Foucault’s work, and then in a long appendix to the Gallimard edition of Histoire de la folie in 1972. The Tel reedition of that text in 1976 drops the two appendices, but they are included in Dits et écrits (as is a translation of the Japanese response and the book’s original 1961 preface, which was removed from the 1972 version). All these texts by Foucault are translated in the 2006 History of Madness. (I list the various editions of Foucault’s book and outline the differences between them here.)

There are also some differences between the journal version of Derrida’s critique and the book version, one of which is discussed by Edward Baring in an important article “Liberalism and the Algerian War: The Case of Jacques Derrida”, published in Critical Inquiry in 2010. I made use of that article in The Archaeology of Foucault, since it was useful in alerting me that there were differences between the article and the book versions. There are some additional notes in the 1967 version, and some other changes. The most important is the one which Baring focuses on, a change of a passage in the article (p. 466) to the book (p. 59 of the French; pp. 42-43 of the English translation).

In The Archaeology of Foucault I also made use of a few letters between Foucault and Derrida, some of which were quoted by Benoît Peeters in his biography of Derrida, and some of which were included in the Derrida Cahier de l’Herne. Some of Derrida’s letters to Foucault are now accessible in the Foucault archive at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. I was looking at these mainly because of Foucault’s correspondence with Georges Dumézil. But the alphabetical proximity of Deleuze to Derrida and Dumézil gave me a chance to have a look at these too. They confirmed the sense I expressed in The Archaeology of Foucault that any break between Foucault and Derrida was not caused by the 1963 lecture, but came somewhat later. In one instance there was the copy of a letter in Cahier de l’Herne which differed slightly – the publication clearly used the version in Derrida’s archive, as he kept a copy. But seeing these letters also indicated something else, which I had previously missed – and in my defence, so had most previous commentators on this debate.

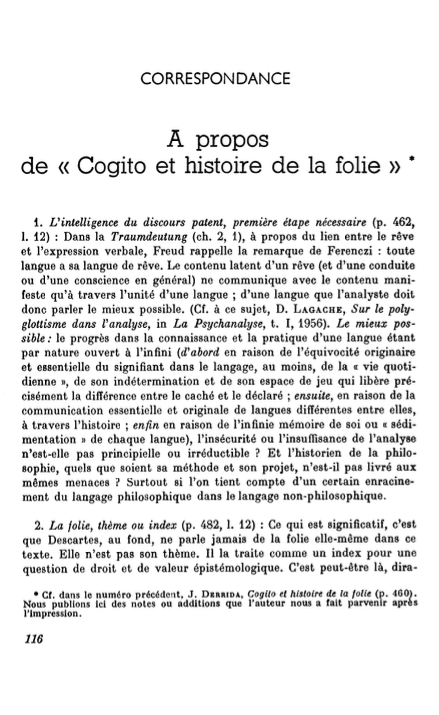

This was the text, “A propos de «Cogito et histoire de la folie»”, which Derrida published in Revue de métaphysique et morale in 1964, in the first issue after the one which included his original critique. It’s a short text of four pages, and Derrida shared the typescript with Foucault before its publication. An editorial note says: “We publish here the notes or additions which the author made available to us after the printing [Nous publions ici des notes ou additions que l’auteur nous a fait parvenir après l’impression]”.

This is the source of most of the additional notes in the book version. Until now, I’d thought these notes only appeared in the book in 1967. This 1964 piece is rarely cited, presumably because the 1967 book or its translation suffices. One piece which does cite it has some useful discussion of how Derrida revised the piece between 1963 and 1967 – Seferin James, “Derrida, Foucault and ‘Madness, the Absence of an Œuvre’”.

Derrida incorporated these additions into the 1967 book version of this text, though with the exception of note 2 did not include the titles of the notes which appeared in 1964:

- Note 1 (1964 article, p. 116) = L’écriture et la différence, pp. 53-54 n. 1; Writing and Difference, p. 390 n. 3.

- Note 2 (1964 article, pp. 116-17) = L’écriture et la différence, p. 79 n. 1; Writing and Difference, p. 392 n. 15.

- Note 3 (1964 article, p. 117) = L’écriture et la différence, p. 81 n. 1; Writing and Difference, p. 392 n. 16.

- Note 4 (1964 article, p. 117) = L’écriture et la différence, p. 83 n. 1; Writing and Difference, pp. 392-93 n. 21. (missing the title of the note)

- Note 5 (1964 article, pp. 117-18) = L’écriture et la différence, p. 89-90 n. 1; Writing and Difference, pp. 393-94 n. 27. (missing the title of the note)

- Note 6 (1964 article, pp. 118-19) = L’écriture et la différence, pp. 90-91 n. 1; Writing and Difference, pp. 294-95 n. 28. Derrida adds “Mais Dieu, c’est l’autre nom de l’absolu de la raison elle-même, de la raison et du sens en général” to the start of the note in 1967.

The other notes were in the 1963 publication, but as Baring and James indicate, there were other changes between that and the book version. I will follow up this post with a list of the other, most substantive, changes between the 1963 article and 1967 book. [Update: now available here]

It’s often remarked that Foucault took a long time to reply to Derrida’s 1963 critique. It’s less often mentioned that the text he was responding to was not fixed until 1967, though as I’ve indicated here, the additional notes were published in 1964.

2. J.M. Pelorson

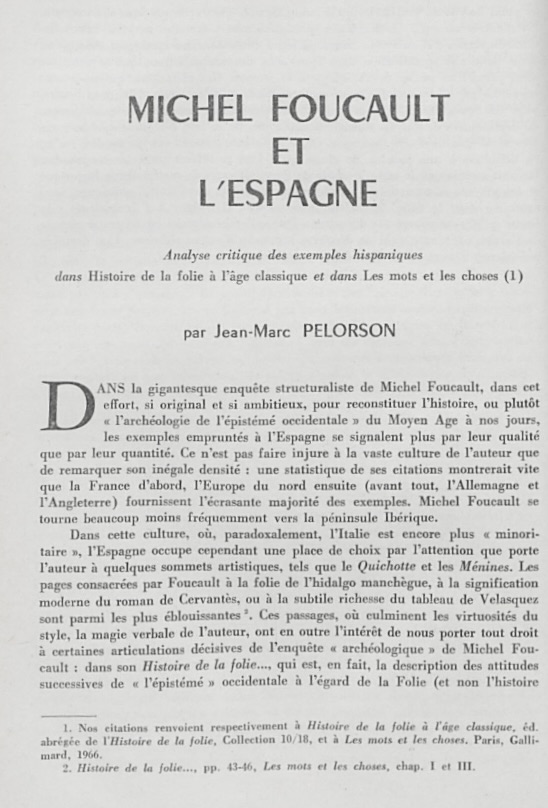

In their September-October 1971 issue, the journal La Pensée published a letter from Foucault, in response to a piece by J.M. Pelorson, “Michel Foucault et l’Espagne: Analyse critique des exemples hispaniques dans Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique et dans Les mots et les choses”, which they had published the previous year. I’ve not found much about the author, Jean-Marc Pelorson. Persée says he was a scholar of Spanish, Dean of the Faculty of Letters at Poitiers, and author of a number of reviews in the Bulletin hispanique. He seems to have been predominantly a Cervantes scholar, which would explain his interest in Foucault’s use of Don Quixote in both History of Madness and The Order of Things.

Foucault’s response is reproduced in Dits et écrits in Vol II of the original edition, Vol I of the Quarto reprint, as text 96. This text is curious because the editors of Dits et écrits reproduce the printed version of the letter but note a number of variants in notes, showing the text which Foucault had written before the editors of La Pensée amended it for publication. There are relatively few texts in Dits et écrits where variants are noted – this is usually done for texts published in two different forms in Foucault’s lifetime, though it is far from complete on this (on which, see here).

At the time Dits et écrits was published, editors were following Foucault’s “no posthumous publications” request strictly. In this instance they were following another logic – although the variants hadn’t been published in Foucault’s lifetime, he had very clearly wanted them to be. In English, most of the text is included in “Monstrosities in Criticism”, which appeared in The New York Times Book Review, which also responds to George Steiner, and is itself translated (back) into French as text number 97. There is no separate English translation of text 96.

Of the review in La Pensée, the editors of Dits et écrits say: “This text had been subject to some amendments on the part of M. Foucault, on the request of Marcel Cornu, who nevertheless modified certain terms [Ce texte avait fait l’objet d’atténtuations de la part de M. Foucault, à la demande de Marcel Cornu, qui en modifia néanmoins certains termes]” (editorial note, Dits et écrits, Vol II, p. 209).

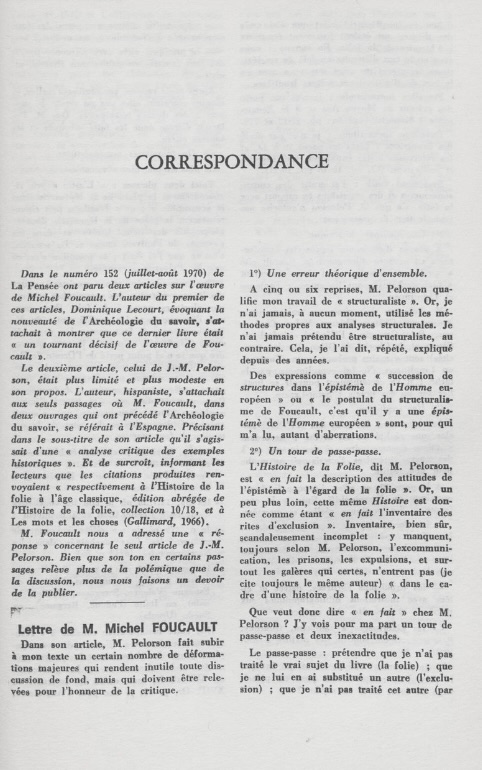

Foucault begins in uncompromising fashion: “In his article, Mr Pelorson subjects my text to a number of major distortions which render any substantive discussion pointless, but which must be noted for the honor of criticism”. The last few words replace the original “for purely moral reasons” (p. 209). One of the criticisms is that Pelorson was working with the shorter abridged version of Foucault’s History of Madness, which has long been discussed as a problem in the anglophone reception of Foucault’s work, but its use is more unusual in a French discussion.

Foucault objects to Pelorson’s characterisation of his work as “structuralist”. “But I have never, at any time, used the methods specific to structural analysis [les méthodes propres aux analyses structurales]. I have never claimed to be a structuralist, on the contrary. This I have said, repeated, explained for years [Cela, je l’ai dit, répété, expliqué depuis des années]” (p. 209). Pelorson’s use of some phrases to characterise Foucault are “for those who have read me, so many aberrations” (p. 210).

Some of Foucault’s original language is indeed striking. He repeatedly claims that Pelorson’s argument is full of “mensonges”, lies, which the published version has as “inexactitudes”, inaccuracies. Foucault’s use of “incertitude” is changed to “ignorance” (p. 210 and the notes on that page). There are other changes, but this gives something of the tone. But there is another change which struck me on looking at this text again. The published version has “Un tour de passe-passe”, but the original “Une jonglerie” – difficult to translate either but perhaps “a sleight of hand” and “a juggling trick”.

When La Pensée published the letter, they preceded it with a brief comment.

In issue number 152 (July-August 1970) of La Pensée, two articles on Michel Foucault’s work appeared. The author of the first of these articles, Dominique Lecourt, indicating the novelty of The Archaeology of Knowledge, sought to show that this latest book was “a decisive turning point in Foucault’s work”.

The second article, by J.M. Pelorson, was more limited and modest in its scope. The author, a Hispanist, focused solely on passages in which Foucault referred to Spain in two works which preceded The Archaeology of Knowledge. He specified in the subtitle of his article that it was a ‘critical analysis of historical examples’. He also informed readers that the quotations referred ‘respectively to Histoire de la folie à l’âge classique, an abridged edition of Histoire de la folie, 10/18 collection, and The Order of Things (Gallimard, 1966).

M. Foucault sent us a ‘response’ concerning only J.M. Pelorson’s article. Although its tone in certain passages is more polemic than discussion, we feel it is our duty to publish it (p. 141, not included in the reprint in Dits et écrits).

Foucault’s archive has two letters from Marcel Cornu concerning this response. The first, of 20 May 1971, acknowledges Foucault’s letter, and expresses surprise and upset about the response, especially its tone, and says that the journal would be within its rights to refuse to publish any of it. But on reflection, they will include the letter in the July issue, so that readers can get a sense of the way Foucault engages with a critic, the tone of his response, and the detailed points he raises. A subsequent letter to Foucault from 18 July 1971 says that there was no room for the letter in the July issue, but that it would still appear, despite Foucault’s refusal to moderate the tone. It appears that the changes which the editors of Dits et écrits indicate were made were despite Foucault’s refusal.

It is not surprising, then, that the editors, Daniel Defert and François Ewald, would have recalled Foucault’s reaction to this, and used the opportunity, 23 years later, to rectify the situation. The text they published means they must have had access to the original, unamended letter. Although Foucault’s response was not published until 1971, I suspect that Pelorson is one of the people he has in mind when he wrote a preface to the English translation of The Order of Things in 1970, in which he said:

This last point is a request to the English-speaking reader. In France, certain half-witted ‘commentators’ persist in labelling me a ‘structuralist’. I have been unable to get it into their tiny minds that I have used none of the methods, concepts, or key terms that characterize structural analysis (p. xv).

The French translation of this text – a translation back into French – refers to them as “certains «commentateurs» bornés” (Dits et écrits, text 72, Vol II, p. 13). That’s a fairly literal translation of the English phrase, perhaps closer to “narrow-minded” than “half-witted”. The original French text of the English preface, in Foucault’s archives and still unpublished, has the word bateleurs, jesters or jokers. The dismissive tone, as well as the substance of the claim, is similar to this response to Pelorson. And, as I have indicated elsewhere, Foucault is being unfair to those who relate his work to structuralism, even if by 1970 he is clearly disassociating himself from this mode of thought.

References

Edward Baring, “Liberalism and the Algerian War: The Case of Jacques Derrida”, Critical Inquiry 36 (2), 2010, 239-61.

Jacques Derrida, ‘Cogito et histoire de la folie’, Revue de métaphysique et de morale 68 (4), 1963, 460-94.

Jacques Derrida, “A propos de «Cogito et histoire de la folie»”, Revue de métaphysique et morale 69 (1), 1964, 116-19.

Jacques Derrida, L’Écriture et la différence, Paris: Seuil, 1967; Writing and Difference, trans. Alan Bass, London: Routledge, 1978.

Stuart Elden, The Archaeology of Foucault, Cambridge: Polity, 2023.

Stuart Elden, “Foucault and Structuralism” in Daniele Lorenzini (ed.), The Foucauldian Mind, London: Routledge, forthcoming 2026.

Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, London: Tavistock, 1970. This text has no named translator, but see my discussion here.

Michel Foucault, “Préface à l’édition anglaise”, trans. F. Durant-Bogaert, in Dits et écrits, eds. Daniel Defert and François Ewald, Paris: Gallimard, four volumes, 1994, Vol II, 7-13.

Michel Foucault, “Lettre de M. Michel Foucault”, La Pensée 159, septembre-octobre 1971, 141-144; reprinted in Dits et écrits, eds. Daniel Defert and François Ewald, Paris: Gallimard, four volumes, 1994, Vol II, 209-14.

Michel Foucault, “Monstrosities in Criticism”, Diacritics 1 (1), 1971, 57-60.

Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, “Lettres de Michel Foucault et de Jacques Derrida, janvier–mars 1963”, in Marie-Louise Mallet and Ginette Michaud eds., Jacques Derrida: Cahier L’Herne, Paris: Éditions de L’Herne, 2004, 111–16.

Seferin James, “Derrida, Foucault and ‘Madness, the Absence of an Œuvre’”, Meta: Research in Hermeneutics, Phenomenology, and Practical Philosophy III (2), 2011, 379-403 (open access).

Dominque Lecourt, “Sur l’Archéologie et le savoir: A propos de Michel Foucault”, La Pensée 152, août 1970, 69-87.

Benoît Peeters, Derrida, Paris: Flammarion, 2010; Derrida: A Biography, trans. Andrew Brown, Cambridge: Polity, 2013.

J.-M. Pelorson, “Michel Foucault et l’Espagne: Analyse critique des exemples hispaniques dans Histoire de la folie a l’âge classique et dans Les mots et les choses”, La Pensée 152, août 1970, 88-99.

Archives

NAF28730, Fonds Michel Foucault, Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc98634s

NAF28804, Michel Foucault. Lettres reçues I, Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://archivesetmanuscrits.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cc1020245

This is the 58th post of a weekly series, posted every Sunday throughout 2025, and now entering a second year. The posts are short essays with indications of further reading and sources. They are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally, but are hopefully worthwhile as short sketches of histories and ideas. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare parts, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome. A few, usually shorter, pieces in a similar style have been posted mid-week. I’m not sure I’ll keep to a weekly rhythm in 2026, but there will be at least a few more pieces.

The full chronological list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here, with a thematic ordering here.