In a previous pieces in this series I’ve discussed Étienne Wolff’s work on the biology of monsters, some of which was written during his time in Oflag XVII-A during the Second World War. (An Oflag was a Offizierslager – a German camp for Allied officers.) I then followed up with a more general post about the French professors who wrote books in these camps, and said a bit about the Université de Captivité which Wolff helped to run, alongside the mathematician Jean Leray. In future work I hope to say a bit more about the teaching in that camp.

In the second of those pieces I mentioned perhaps the most famous book written in German captivity, Fernand Braudel’s La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l’époque de Philippe II. It was first published in 1949 and translated as The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II. Lucien Febvre was fundamental in the shift of emphasis: “Philip II and the Mediterranean is a fine subject. But why not the Mediterranean and Philip II? Isn’t that an even more fascinating subject? Because between the two protagonists, Philip and the internal sea, the match is not equal” (Febvre, “Un livre qui grandit”, p. 217). François Dosse comments on this move: “Thus history changed its subject, no longer Philip II but the Mediterranean, a geographical subject for a historian. It was a decisive manoeuvre that Braudel skilfully mastered as he took up the suggestion and the legacy of Febvre” (New History in France: The Triumph of the Annales, p. 108).

In a piece on his intellectual formation, first published in English in 1972, Braudel discusses meeting Febvre, his imprisonment and the book’s composition.

In the summer of 1939 at Souget, in Lucien Febvre’s house, I prepared to begin writing my book. And then the war! I served on the Rhine frontier. From 1940 to 1945 I was a prisoner in Germany, first in Mainz, then from 1942 to 1945 in the special camp at Lübeck, where my Lorrainer’s rebelliousness sent me. As I returned safe and sound from this long time of testing, complaining would be futile and even unjust; only good memories come back to me now. For prison can be a good school. It teaches patience, tolerance. To see arriving in Lübeck all the French officers of Jewish origin – what a sociological study! And later, sixty-seven clergymen of every hue, who had been judged dangerous in their various former camps – what a strange experience that was! The French church appeared before me in all its variety, from the country curé to the Lazarist, from the Jesuit to the Dominican. Other experiences: living with Poles, brave to excess; and receiving the defenders of Warsaw, among them Alexander Gieysztor and Witold Kula. Or to be submerged one fine day by the massive arrival of Royal Air Force pilots; and living with all the French escape artists, who were sent to us as a punishment; these are – and I omit much – among the picturesque memories.

But what really kept me company during those long years – that which distracted me in the true etymological meaning of the word – was the Mediterranean. It was in captivity that I wrote that enormous work, sending school copy book after school copy book to Lucien Febvre. Only my memory permitted this tour de force. Had it not been for my imprisonment, I would surely have written quite a different book (“Ma formation d’historien”, pp. 14-15; “Personal Testimony”, p. 453).

Braudel apparently had to be persuaded quite hard to write down these memories (see Marino, “The Exile and His Kingdom”, p. 624 n. 11), and as far as I’m aware, wrote little else about his time in a camp. He did however edit an issue of the Revue d’histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale on the question of captivity, to which he contributed a short preface, but it says little about his personal experience.

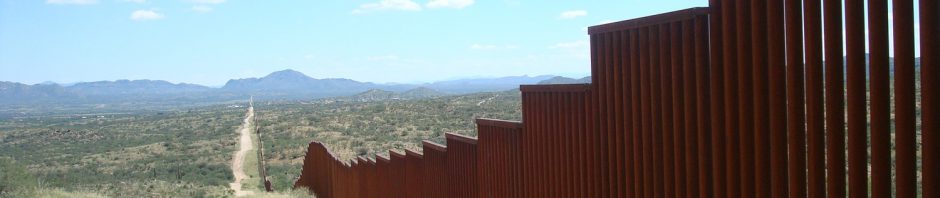

The two camps he mentions in his testimony are Oflag XII-B in Mainz and Special Oflag X-C in Lübeck, and the transfer from one to the other he attributes to his “Lorrainer’s rebelliousness”, and was likely down to his Gaullist sympathies. (The question of the relation between Pétainist and Gaullist elements within the army and especially in the camps is a whole other topic.) He was able to access some books while in the camp, including from the local library, but had to rely on his memory for a great deal. He wrote at least one article published during his captivity, published in 1943, and a book review of Gaston Roupnel, Histoire et destin which he sent to Febvre and was published in the final year of the occupation. An editorial note to the article says that while Braudel was able to compose the article and send it to the journal he was unable to review the proofs (p. 3). The school notebooks in which he composed the draft of the Mediterranean study, and which he sent regularly to Febvre, were unfortunately destroyed after he had revised the text. It is generally said that it was Braudel’s standard practice to destroy drafts of completed books (Pierre Daix, Braudel, p. 165 n. 1; editor note to Les Écrits de Fernand Braudel, Vol II, p. 11), but Erato Paris says two notebooks survive (La genèse intellectuelle de l’oeuvre de Fernand Braudel, p. 306). Another piece from the war was published as the first essay in the relaunched Annales after the war, on coins and civilisations, from gold in the Sudan to American silver. One indication of the provenance of this particular text comes in its form – unusually for a historical work, it has no footnotes.

The book on the Mediterranean does have extensive notes, and if Braudel had access to limited sources during the war he was able to rework it afterwards when back in Paris, before defending it as his thesis. Based on the limited sources which survive, there is a surprising amount about the composition of the book. The most thorough accounts I know of the book’s composition are by Erato Paris in the final part of La genèse intellectuelle de l’oeuvre de Fernand Braudel, as well as Chapter VI of the biography of Braudel by Daix. Both Paris and Daix make a lot of use of correspondence to shed light on the experience of writing in the camp, especially the unpublished Braudel-Febvre letters. Dosse indicates that while much of the writing was done in the camps, much of the research was done before the war: “This fact disproves the hypothesis according to which the book’s structure was conceived as an antidote to the German news about the war, as if it were a form of escape into long duration in contrast to the daily events broadcast over Nazi radio” (New History in France, p. 108).

On Braudel’s experience in the camp and the writing of this text, the account by his widow Paule Braudel, first published in Italian and later in French, is very good, and expands in some respects on her earlier “Les origines intellectuelles de Fernand Braudel: Un témoignage”. Paule Braudel explains that the Braudel-Febvre correspondence, which is in the Archives Nationales, has been prepared for publication. The originals of the letters are apparently now too fragile to be consulted, and her edition of the text was established on the basis of a photocopy. It would undoubtedly reveal more of the story, but has not been published due to the wishes of one of Febvre’s heirs.

In English, there is a chapter by Peter Schöttler, which discusses the writing of the book and his correspondence with Febvre, and an article by Howard Caygill, “Braudel’s Prison Notebooks”. Caygill led me to the Annales article which came from this period (p. 155). He also notes that Henri Pirenne, the Belgian historian who was important in the early years of the Annales, and who had an extensive correspondence with Marc Bloch and Febvre, had first presented his History of Europe as lectures in a camp in World War One (p. 153). According to his “Souvenirs de captivité en Allemagne (mars 1916-novembre 1918)”, Pirenne, who was forbidden access to books, learnt Russian from a Russian officer and then later read Russian history books which gave him a different perspective on Europe’s history. His son Jacques Pirenne’s preface to the posthumously published History of Europe gives more details.

Braudel’s article and review in 1943 and 1944 were published during the short period when the Annales journal, which had several variant names over the years, was called Mélanges d’histoire sociale. Bloch and Febvre had disagreed on how to respond to German censorship and Vichy laws excluding Jews from academic positions. In the end there was a compromise: the journal would change name, and no editors were listed, so that Bloch, who was Jewish, was neither formally removed as editor nor publicised. All the content was subject to German and Vichy censorship, as were all publications in France during the Occupation. (I write about the ‘Liste Otto’ of prohibited books here, in relation to Henri Lefebvre.) Bloch continued to write for the Mélanges under the pseudonym Marc Fougères. The third volume of the Bloch-Febvre correspondence is useful for their discussions about how best to handle the constraints of the Occupation. (On the story of Annales during the war, Natalie Zemon Davis’s articles “Rabelais among the Censors” and “Censorship, Silence and Resistance” are very good, and Chapter 20 of Philippe Burrin’s Living with Defeat is also useful. There are many books on intellectuals in the Occupation generally, of which Gisèle Sapiro, The French Writers’ War is particularly good.)

I had not known until recently that some of Braudel’s lectures from the Oflag were published as “L’histoire, mesure du monde”. The French version is in the second volume of the posthumous Écrits de Fernand Braudel – a three-volume collection, recently reissued as a single volume. (Écrits de Fernand Braudel should not be confused with Écrits sur l’histoire, published in his lifetime, with a second posthumous volume, even though there is a lot of overlap of content.) “L’histoire, mesure du monde” is an introductory course on history, but as far as I’m aware these lectures are not available in English. The lectures are interesting for many reasons, including the discussions of different temporalities, the relation between history and geography, and the idea of geohistory, and the approach of the historian to their material. There is some discussion of different French and German approaches to history, intriguing given they were delivered by a Frenchman in a German camp, but also probably due to his limited access to reading material at the time. They date from the time Braudel was drafting the book on the Mediterranean, and it’s striking he was outlining how to do history at this early stage of his interrupted career. They deserve fuller treatment.

As I indicated in a previous post, the more I explore this topic, the more I realise how important the experience of captivity was to so many intellectual careers and work in the middle of the twentieth century.

References

Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre, Correspondance Tome III: Les «Annales» en crise (1938-1943), ed. Bertrand Müller, Paris: Fayard, 2003.

Fernand Braudel, “À travers un continent d’histoire. Le Brésil et l’œuvre de Gilberto Freye”, Mélanges d’histoire sociale 4, 1943, 3-20.

Fernand Braudel, “Faillité de l’histoire: Triomphe du destin?” Mélanges d’histoire sociale 6, 1944, 71-77.

Fernand Braudel, La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l’époque de Philippe II, Paris: A. Colin, three volumes, 1949, second edition 1966; The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, trans. Siân Reynolds, London: Fontana, two volumes, 1975.

Fernand Braudel, “La captivité devant l’histoire”, Revue d’histoire de la deuxième Guerre Mondiale 7 (1), 1957, 3-5.

Fernand Braudel, “Monnaies et Civilisations: De l’or du Soudan à l’argent d’amerique: Un drame mediterranéen”, Annales. Economies, sociétés, civilisations 1 (1), 1946, 9-22; reprinted in Les Ambitions de l’histoire: Écrits de Fernand Braudel Vol 2, Editions de Fallois, Paris, 1997, 277-95.

Fernand Braudel, “Personal Testimony”, The Journal of Modern History 44 (4), 1972, 448-67; later published in French as “Ma formation d’historien” in Écrits sur l’histoire II, Paris: Flammarion, 1994, 9-29.

Fernand Braudel, “L’histoire, mesure du monde”, edited by Paule Braudel and Roselyne de Ayala in Les Ambitions de l’histoire: Écrits de Fernand Braudel Vol 2, Editions de Fallois, Paris 1997, 11-83.

Paule Braudel, “Les origines intellectuelles de Fernand Braudel: Un témoignage”, Annales: Economies, sociétés, civilisations 47 (1), 1992, 237-44.

Paule Braudel, “Prefazione all’edizione italiana”, in Fernand Braudel, Storia, misura del mondo, Bologna: Il Mulino, 1998, 7-20; revised version as “Braudel en captivité”, in Paul Carmignani ed., Autour de F. Braudel, Perpignan: Presses Universitaires de Perpignan, 2002, 13-25, https://books.openedition.org/pupvd/3839?lang=en

Philippe Burrin, Living with Defeat: France Under the German Occupation 1940-1944, trans. Janet Lloyd, London: Arnold, 1996.

Paul Carmignani ed., Autour de F. Braudel, Perpignan: Presses Universitaires de Perpignan, 2017.

Howard Caygill, “Braudel’s Prison Notebooks”, History Workshop Journal 57, 2004, 151-60.

Pierre Daix, Braudel, Paris: Flammarion, 1995.

François Dosse, New History in France: The Triumph of the Annales, trans. Peter V. Conroy, Jr., Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1994.

Lucien Febvre, “Un livre qui grandit: La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen”, Revue historique 203, 1950, 216-24.

Bryce and Mary Lyon, The Birth of Annales History: The Letters of Lucien Febvre and Marc Bloch to Henri Pirenne (1921-1935), Brussels: Palais des Académies, 1991.

John A. Marino, “The Exile and His Kingdom: The Reception of Braudel’s Mediterranean”, Journal of Modern History76 (3), 2004, 622-52.

Erato Paris, La genèse intellectuelle de l’oeuvre de Fernand Braudel: La Méditerranée et le monde méditerranéen à l’époque de Phillipe II, 1923-1947, Athènes: Institut de recherche néohelléniques/FNRS, 1999.

Henri Pirenne, Histoire de l’Europe des invasions au XVIe siècle, Paris, Alcan, 1936; A History of Europe from the Invasions to the XVI Century, London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd, 1939.

Henri Pirenne, “Souvenirs de captivité en Allemagne (mars 1916-novembre 1918)”, https://www.larevuedesressources.org/souvenirs-de-captivite-en-allemagne-mars-1916-novembre-1918,2187.html

Gaston Roupnel, Histoire et destin, Paris: Bernard Grasset, 1943.

Gisèle Sapiro, La Guerre des écrivains 1940-1953, Paris: Fayard, 1999; The French Writers’ War, 1940-1953, Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

Peter Schöttler, “Fernand Braudel as Prisoner in Germany: Confronting the Long Term and the Present Time”, in Anne-Marie Pathé, Fabien Théofilakis, eds., Wartime Captivity in the Twentieth Century: Archives, Stories, Memories, trans. Helen McPhail, New York: Berghahn, 2016, 103-14. (A translation of Anne-Marie Pathé and Fabien Théofilakis (éds.), La Captivité de guerre au XXème siècle. Des archives, des histoires, des mémoires, Paris, Armand Colin, 2012.)

Natalie Zemon Davis, “Rabelais among the Censors (1940s, 1540s)”, Representations 32, 1990, 1-32.

Natalie Zemon Davis, “Censorship, Silence and Resistance: The Annales during the German Occupation of France”, Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques, 24 (2), 1998, 351–374.

This is the 53rd post of a weekly series, posted every Sunday throughout 2025, and now entering a second year. The posts are short essays with indications of further reading and sources. They are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally, but are hopefully worthwhile as short sketches of histories and ideas. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare parts, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome. A few, usually shorter, pieces in a similar style have been posted mid-week. I’m not sure I’ll keep to a weekly rhythm in 2026, but there will be at least a few more pieces.

The full chronological list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here, with a thematic ordering here.