Call for papers: Curzonic geographies/Reading ‘Frontiers’

Call for papers: Curzonic geographies/Reading ‘Frontiers’

RGS-IBG conference, 1-4 September 2020

organised by Richard Schofield (KCL) and Matthew Tillotson (Leicester) – contact Matthew with any queries

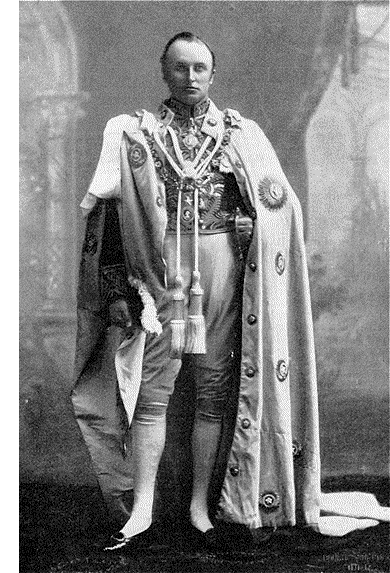

As an embodiment of a classic, privileged travel writer George Curzon (1859-1925) documented his Central Asian, Persian and Far Eastern sojourns. Later, as the last Victorian viceroy of India (1899-1905), Curzon was the architect of both a ‘brilliantly organized famine’ (Davis 2017: 174) and Britain’s ‘Oriental’ borderlands. And with his 1907 Romanes lecture on ‘Frontiers’ in Oxford, Curzon articulated a ‘science’ on boundaries as an academic and intellectual project vital to British imperial interests.

Curzon the viceroy was heir to, and the advocate of utilitarian, Benthamite experiments in biopower. British liberals had long channelled Malthusian, social Darwinist and evangelical thought to justify the deaths of millions in the colonised world. Imperial wars and the retrenchments of free market ideology obscured genocidal imperial policy and framed famine relief as an obscene, inefficient response to overpopulation in India. But it was not only free market economics (in the tradition of Haileybury and the East India Company) that Curzon prized and he regarded geography as ‘one of the first and foremost of the sciences’ (Curzon 1915), vital for a period in which the imperial scramble for supposedly ‘vacant’ spaces would conclude.

Frontier policy would therefore provide ‘incessant employment for the keenest intellects and the most virile energies of the Anglo-Saxon race’ (Curzon 1907: 5). In ‘Frontiers’ and on foreign policy and territorial questions, Curzon’s thought was characterised by an environmental determinism that is qualified and never absolute: although preferring facts over generalisations still he sought to explain ‘the action of great natural forces’ (Curzon 1915: 156) over imperial policy, commerce and the distribution of settler colonial populations. Further, Curzon espoused a ‘pedagogical view of empire’ (Said 2003: 213). With the Orient recognised as Britain’sobligation, imperial space was interpreted as a political, historical and social fact. Not only was a perpetual British presence required overseas – the empire had continually to be studied.

At this session we invite panellists to discuss the troubling legacies of ‘Curzonic’ geographies: the biopolitics of hunger and famine, the interface between geographical knowledge and the projection of imperial power, and critical interpretations of ‘Frontiers’. We interpret ‘Curzonic’ broadly and welcome contributions that touch on these (and other) themes over and above Curzon’s life and times.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you Stuart!