Superficially at least, the stories of Vladimir Nabokov (1899-1977) and Roman Jakobson (1896-1982) would seem to connect. Both were born in Russia – Nabokov in Saint Petersburg; Jakobson in Moscow; both went into exile after the Revolution – Nabokov in Cambridge and Berlin; Jakobson in Czechoslovakia then Scandinavia – before both moved to the United States.

They both taught in elite US institutions. Jakobson was the career academic, teaching at the École Libre des hautes études (ELHE), alongside Koyré, Lévi-Strauss and Jean Gottmann, among others, and then at Columbia University and Harvard University. In his final years he had an affiliate position at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Nabokov was primarily a novelist but also taught at Wellesley College and Cornell University. The historian Marc Moise Szeftel (1902-1985) had a similar life and career, escaping Ukraine to Poland, Belgium and then via France and Spain to the United States, teaching at Columbia, Cornell University and the University of Washington.

In the mid-1950s Nabokov was being considered for a chair in Russian Literature at Harvard, and there was support from some academics, but it was apparently Jakobson who destroyed his chances with a brutal, if very funny, putdown. Nabokov’s biographer Brian Boyd tells the story of a department discussion of the possibility:

There Roman Jakobson, the star performer in Harvard’s Slavic troupe, staunchly opposed someone else who might take top billing and attacked Nabokov for his quirky ideas on Dostoevsky and other great Russian novelists. Nabokov’s advocates asked if he were not a very distinguished novelist in his own right. Jakobson replied: “Gentlemen, even if one allows that he is an important writer, are we next to invite an elephant to be Professor of Zoology?” No one managed to parry that thrust (Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, p. 303; compare Galya Diment, Pniniad, p. 39).

Jakobson must have known that Nabokov had actually worked at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology as a curator of butterflies while teaching at Wellesley College. (On his lifelong work as a lepidopterist, see Nabokov’s Butterflies.)

Nabokov of course learned of this opposition through mutual friends, and the acrimony was doubtless part of the reason for a failed collaboration between the two of them on an English translation of “The Song of Igor”. This was a Russian poem, alternatively known as “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign” or other variants. It dated from probably from the late 12th century or the early 13th, and was written in Old East Slavic. Jakobson had worked on a critical edition of the text with Henri Grégoire and Szeftel as La Geste du Prince Igor’, published in 1948. Though appearing with Columbia University Press, the essays and apparatus in the book were in French: this was a collaboration between scholars who had met at the ELHE, and the text was formally volume 8 of the Annuaire de l’Institut de philologie et d’histoire orientales et slaves. (A collaborative course on the text had been taught at the ELHE in 1942-43, with others involved, including Alexandre Koyré.) While the volume also included French and English translations, Jakobson’s contribution was the edition of the text, a modern Russian translation and an essay on the authenticity of the text. His parts are reprinted in his Selected Writings Volume IV.

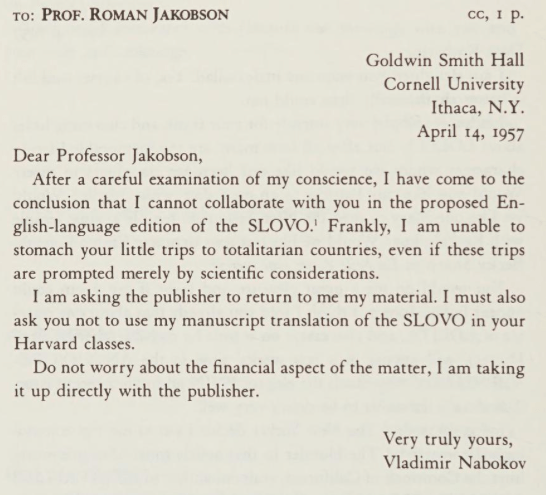

Nabokov wrote a review essay of this volume, and Boyd tells the story of how he struggled to find a journal for it. Approaching Jakobson, the suggestion was made that Nabokov’s translation was included alongside the Russian text and notes for an English edition. This was for a series Jakobson was going to edit of Russian classics for students, and Nabokov agreed, suggesting also his translation of Eugene Onegin for the series (Boyd, p. 145). Around 1957 – following this slight at Harvard – Nabokov broke this collaboration off. There were other reasons – perhaps due to ideological differences, perhaps due to literary approaches. Boyd also tells the story of dinner party that did not go well (p. 215). Nabokov objected to Jakobson’s ties to the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Boyd picks up the story:

He had had a contract for years with the Bollingen Press for an annotated English edition of The Song of Igor’s Campaign to be prepared with Marc Szeftel and Roman Jakobson. All three contributors had been paid an advance. Although in no position to repay his share, Nabokov wanted to withdraw from the joint edition rather than work with Jakobson. To his delight, Bollingen agreed not to demand he return his part of the advance. He promptly wrote to Jakobson, explaining that he wanted to withdraw from their joint project on account of ‘your little trips to totalitarian countries.’ He had heard that the year before, in Moscow for a conference, Jakobson had wept at his return to the city, and had promised to come back soon. Nabokov was in fact convinced that Jakobson was a Communist agent. At a time when university faculties were hostile to the search for Communists on their campuses, Nabokov befriended the FBI agent assigned to Cornell and declared he would be proud to have his son join the FBI in that role. No wonder it was impossible for him to work alongside Jakobson (p. 311; the letter is from 14 April 1957).

In the end, Nabokov made the English translation alone, published in 1960. He told Gleb Struve that it was “without the collaboration of the unacceptable Roman Jakobson” (3 June 1959). In this translation, Nabokov only briefly acknowledges the history:

I made a first attempt to translate Slovo o Polku Igoreve in 1952. My object was purely utilitarian—to provide my students with an English text. In that first version I followed uncritically Roman Jakobson’s recension as published in La Geste du Prince Igor. Later, however, I grew dissatisfied not only with my own—much too ‘readable’—translation but also with Jakobson’s views. Mimeographed copies of that obsolete version which are still in circulation at Cornell and Harvard should now be destroyed (p. 82 n. 18)

Nabokov was very critical of previous editions: “I have also seen The Tale of the Armament of Igor, edited and translated by Leonard A. Magnus, Oxford, 1915, a bizarre blend of incredible blunders, fantastic emendations, erratic erudition and shrewd guesses” (p. 19).

Nabokov did not spare the other scholars who had worked on the Song of Igor either. Of the French Slavist philologist André Mazon, he said his study “while containing many interesting juxtapositions, is fatally vitiated by his total incapacity of artistic appreciation” (p. 81 n. 17). His feud with Mazon was in part about the interpretation of the Song in relation to other Russian tales, with Mazon believing it was a much later forgery. There is also a debate about whether the Song is based on the Zadonschina, or if the Song preceded that and was its model. The debate is complicated by the destruction of the only manuscript in Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, leading to debates about its authenticity. But the Mazon-Nabokov dispute also fed into Mazon’s opposition to any innovations in linguistics being brought to bear on literary analysis. Mazon and his brother Paul (a Greek scholar) were a powerful force at the Collège de France, where they both had chairs. André Mazon was opposed to anyone with links to Jakobson. He tried, unsuccessfully, to prevent Georges Dumézil’s election in 1949, but they were part of the initial opposition to Claude Lévi-Strauss’s election around 1949-50, alongside the administrator Edmond Faral. Lévi-Strauss was eventually elected a decade later, after Mazon and Faral had retired.

The proposed English edition of The Song of Igor for Bollingen was never published. Szeftel was unhappy Nabokov did not acknowledge his and Jakobson’s comments in his version (see Diment 1997, pp. 40-41). The Igor translation contract with Bollingen Press is interesting in itself, since this was the English-language outlet for publications from the Olga Froebe-Kapteyn and Carl Jung-led Eranos circle, funded by the Mellon family. Nabokov’s translation of Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin did appear in this series in four volumes in 1964. One contained an Introduction and the translation, there were two volumes of commentary, and a fourth with a photo-reproduction of the Russian text and an index. The professor in Nabokov’s Pnin has been compared to Szeftel, Jakobson, and Nabokov himself, though Nabokov denied at least Szeftel was the model (see Boyd pp. 288-89; Diment 1996 and 1997). Most likely Timofey Pnin is a composite of them and others, but as Diment indicates, he is working on a study of a text which sounds remarkably like the Song.

Update 4 May 2025: Some further sources for this story are discussed here.

9 Nov 2025: I discuss Nabokov’s original translation and Jakobson’s intent to complete his edition here.

References

La Geste du Prince Igor’: Épopée Russe du douzième siècle, ed. and trans. Henri Grégoire, Roman Jakobson and Marc Szeftel, New York: Columbia University Press, 1948.

The Song of Igor’s Campaign: An Epic of the Twelfth Century, trans. and foreword by Vladimir Nabokov, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1960.

Victoria A. Baena, “Past Tense: Nabokov and Jakobson”, The Harvard Crimson, 4 October 2012, https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2012/10/4/nobokov-jakobson-harvard-academy/

David M. Bethea and Siggy Frank (eds.), Vladimir Nabokov in Context, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Brian Boyd, Vladimir Nabokov: The American Years, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991.

Galya Diment, “Timofey Pnin, Vladimir Nabokov, and Marc Szeftel”, Nabokov Studies 3, 1996, 53-75.

Galya Diment, Pniniad: Vladimir Nabokov and Marc Szeftel, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Roman Jakobson, Selected Writings IV: Slavic Epic Studies, The Hague: Mouton & Co, 1966.

André Mazon, Le Slovo d’Igor, Paris: Librairie Droz, 1940.

Vladimir Nabokov, Pnin, London: Penguin, 1997 [1957].

Vladimir Nabokov, Selected Letters, 1940-1977, eds. Dmitri Nabokov & Matthew J. Bruccoli, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1990.

Vladimir Nabokov, Nabokov’s Butterflies: Unpublished and Uncollected Writings, eds. Brian Boyd and Robert Michael Pyle, trans. Dimitri Nabokov, Boston: Beacon Press, 2000.

Aleksandr Pushkin, Eugene Onegin: A Novel in Verse, trans. and ed. Vladimir Nabokov, New York: Bollingen Foundation, four volumes, 1964.

Marc Szeftel, “Correspondence with Vladimir Nabokov and Roman Jakobson”, in Galya Diment, Pniniad: Vladimir Nabokov and Marc Szeftel, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997, 103-119.

Lisa Wakamiya, “Nabokov’s ‘The Song of Igor’s Campaign’” (abstract for 7 November 2018 talk), Amherst College, https://www.amherst.edu/academiclife/departments/russian/acrc/events/node/726508

Archives

Marc Szeftel papers, University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, https://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:80444/xv48364

Archives relating to Vladimir Nabokov are listed here – https://thenabokovian.org/archives

Roman Jakobson papers, MIT, https://archivesspace.mit.edu/repositories/2/resources/633

This is the sixth post of an occasional series, where I try to post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome. The other posts so far are:

Benveniste, Dumézil, Lejeune and the decipherment of Linear B – 5 January 2025

Foucault’s 1972 visit to Cornell University – 12 January 2025 (updated 14 January)

Benveniste and the Linguistic Circle of Prague – 19 January 2025

Marie-Louise Sjoestedt (1900-1940): an important scholar of Celtic languages and mythology – 26 January 2025

Thomas Sebeok, Umberto Eco and the Semiotics of Nuclear Waste – 2 February 2025

Ernst Kantorowicz and the California Loyalty Oath – 16 February 2025

The full list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Marie-Louise Sjoestedt (1900-1940): an important scholar of Celtic languages and mythology | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Thomas Sebeok, Umberto Eco and the Semiotics of Nuclear Waste | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Benveniste and the Linguistic Circle of Prague | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Foucault’s 1972 visit to Cornell University | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Benveniste, Dumézil, Lejeune and the decipherment of Linear B | Progressive Geographies

patients

https://newbooksnetwork.com/writing-mad-lives-in-the-age-of-the-asylum-2

Pingback: Ernst Kantorowicz and the California Loyalty Oath | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Sunday histories – short essays on Progressive Geographies | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Walter B. Henning, Robert Oppenheimer, Ernst Kantorowicz, the Institute for Advanced Study and the Khwarezmian Dictionary Project | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: The Friendship between Hannah Arendt and Alexandre Koyré | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Alexandre Koyré’s Wartime Teaching at the École Libre des Hautes Études and the New School | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Vladimir Nabokov, Roman Jakobson, and The Song of Igor – other sources for the story of a failed collaboration | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 28: archives in Princeton, Chicago and final work in New York | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Roman Jakobson, Franz Boas, and the Paleo-Siberian and Aleutian material at the New York Public Library | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Vladimir Nabokov’s original and unpublished translation of The Discourse of Igor’s Campaign; and Roman Jakobson’s enduring wish to complete his English edition | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Vladimir Nabokov’s original and unpublished translation of The Discourse of Igor’s Campaign; and Roman Jakobson’s enduring wish to complete his English edition | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Gordon and Tina Wasson, Slavic Studies in the Cold War, and the Hallucinogenic Mushroom | Progressive Geographies