This was written for an event on ‘Troubling Classical Bodies‘ at the Remarque Institute at New York University on 11 April 2025. My thanks to Stefanos Geroulanos and Brooke Holmes for the invitation to give this short talk, and to them, Anurima Banerji and the audience for the discussion.

There is a video of the session here.

In 1907, the British-Hungarian explorer Aurel Stein negotiated with a Buddhist monk to access the library cave of a temple complex in Dunhuang, in Chinese Turkestan, now part of Gansu province and relatively close to the border with Xinjiang. The library cave had been sealed sometime around the 11th-13th century of the modern era, and it contained a wealth of material in a range of languages. Stein paid the monk a small sum to be used for temple renovation, and in return was able to remove manuscripts and bring them back to London. The French scholar Paul Pelliot arrived at Dunhuang in 1908, and made a rapid survey of the material there. He too was able to bring back a huge range of documents to Paris.

Back in Europe, various academics were set to work on the material. Stein was an Indologist, Pelliot a Sinologist, but others were brought on board. The French linguist Antoine Meillet did some work on the language known as Tocharian B, but on the largely unknown Sogdian, an East Iranian language, he got one of his students, and at the time his designated successor, Robert Gauthiot, to do the work. In parallel, German scholars led by Friedrich Carl Andreas were working with other Sogdian texts brought back by the Turfan expeditions. Gauthiot died from wounds received in the First World War, and progress on deciphering and publishing the texts slowed. Gauthiot’s grammar was left incomplete until the very young Emile Benveniste, a student of Meillet and now being prepared as Meillet’s successor – and Gauthiot’s replacement – took up the work.

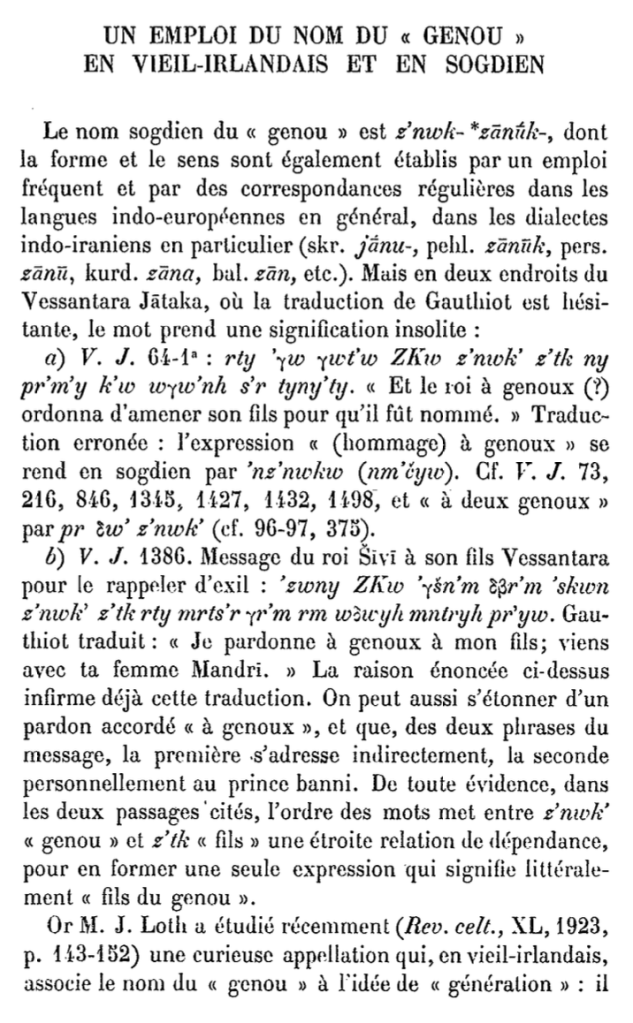

One of Benveniste’s very earliest publications, in 1926, when he was in his early 20s, is on a question of Sogdian vocabulary. It was his second short article in the Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris; a journal in which he would publish much of his work and later edit. It is on the word for ‘knee [genou]’, z’nwk- *zānūk, and he says its sense in Sogdian texts is usually clear from context, or in relation to Indo-European languages generally, and to Indo-Iranian in particular.

But there are two instances in Robert Gauthiot’s translation of the Vessantara Jātaka where the meaning is unclear. The Vessantara Jātaka is a Buddhist tale, about one of the Buddha’s past lives, in which the prince Vessantara gives away all that he owns, including his wife and children, as an exemplar of generosity. There are versions of the tale in many languages, including Pali, Sanskrit and Chinese. The story was known in these other languages, and the discovery of the story in Sogdian helped with that language’s interpretation. Gauthiot published “Une version sogdienne du Vessantara Jātaka” in two parts in the Journal Asiatique in 1912, comprising a transcription and translation. It was also reprinted as a book.

In his article, Benveniste gives the Sogdian text and Gauthiot’s translation. VJ = line number of the transliteration.

VJ 64 – “the king on his knees (?) ordered his son to be brought forward so he could be named [le roi à genoux (?), ordonna d’amener son fils pour qu’il fût nommé]”.`

VJ 1386 – “I forgive my son on my knees; come with your wife Mandri [Je pardonne à genoux à mon fils; viens avec ton épouse Mandri]”.

Benveniste questions both of these choices. It is not normal to order or to forgive on your knees, rather you would beg forgiveness that way. The figure in the position of power is not the one making the supplication. In the second case there is another complication: it is addressed to the “son on knees” or the “son of the knee [fils du genou]” (p. 51).

Benveniste draws on an article by Joseph Loth in the Revue Celtique in 1923, about an Old Irish use of ‘knee’ that invokes a generation, in the sense of “infant of the knee”, and there is a parallel in Anglo-Saxon (i.e. Old English), of the sense of a direct parent. Loth makes a link between sitting in the lap, of a father recognising a child by lifting them up and placing them on their knee. Benveniste thinks this more plausible than the ‘knee’ being a euphemism for a penis, or childbirth from a kneeling woman (p. 52). He argues that even if that was the child birthing practice, the lineage argument is a challenge:

But there’s a long way to go from the purely physiological notion of ‘giving birth’ to the entirely legal one of ‘filiation’, for in primitive societies there is no necessary relationship between consanguinity and kinship. Kinship is only sanctioned by legitimation, which, among Indo-Europeans, is the exclusive prerogative of the father. By taking the child on his lap, after lifting him from the ground, the head of the family exercises one of his essential prerogatives, attesting to the authenticity of his descent, and maintaining the continuity of his lineage (p. 53).

Benveniste therefore suggests that the Irish sense maps onto the Sogdian one, and helps to unlock a puzzle of meaning. (It’s worth noting that the limited surviving materials in Sogdian make for many such challenges in its interpretation.) If “son of the knee” in the earlier examples from the Vessantara Jātaka actually mean ‘son as heir’ or ‘heir-son’, then the difficulties of sense disappear:

VJ 64 – “and the king ordered his heir-son to be brought forward, etc. [Et le roi ordonna d’amener son fils héritier, etc.]”.

VJ 1386 – “I forgive my heir-son; come with your wife Mandri [J’accorde mon pardon, ô mon fils héritier; reviens ici avec ta femme Mandri]”.

He notes that there are no other Iranian dialects that have a similar expression, nor is it found in modern Indian languages.

So we can’t decide whether we’re dealing here with a creation or a calque [i.e. a literal word-for-word translation], a noble or popular expression, a chance conservation or a living locution. But the concordance of a designation and no doubt of an identical usage at the two most distant ends of the Indo-European world seems to us worthy of note, and deserves to be joined to the similar correspondences grouped by M. [Joseph] Vendryes.

What is interesting about this short, three-page article, it seems to me, is that Benveniste is already working in a related manner to his much more renowned later work. A small issue in a text, what might appear to be a textual crux, a corrupted or problematic passage, which might need to be corrected in the source text before being open to translation and interpretation, can be examined from another angle. But the reading of the text can also indicate something about the practices of the people – the idea of kinship, lineage, and patriarchy. Benveniste published a new edition of Vessantara Jātaka in 1946, indicating that though Gauthiot’s work was pioneering, aspects of it were outdated by the 1940s. It was a transliteration, translation and commentary on the text. In the two instances at stake, Benveniste now translates the term as “dear son” or “loving or sweet son”.

VJ 64 “the king ordered his dear son to be brought in for the proclamation (of the name?) [le roi ordonna d’amener son cher fils pour la proclamation (du nom?)]”.

VJ 1386 “I grant my forgiveness, my loving son. Come back with your wife Mandri! [J’accorde mon pardon, ô mon tendre fils. Reviens ici avec ta femme Mandri!]”

Benveniste describes his edition of the Vessantara Jātaka as completing the work of his Textes sogdiens – a transliteration, translation, commentary and glossary of available material, completed shortly before he was called up for his military service and published in 1940. A reproduction of all the previously-unpublished Sogdian manuscripts in Paris, Codices Sogdiani, was sent to the printer shortly before war broke out, and the texts were moved from Paris for safe-keeping. Benveniste wrote its introduction.

Benveniste would continue to work on the Sogdian language throughout his career. The text on the knee was also reprinted as the first text in the posthumous collection of his Études sogdiennes in 1979, edited by his former student Georges Redard after Benveniste’s death.

While Benveniste worked on many other topics, and languages, his career was fundamentally shaped by the findings of expeditions to the Silk Road which happened when he was a young child. The haul of Stein and, especially, Pelliot provided a wealth of material for scholars. And in his first publications on the Sogdian language, Benveniste is one of the major figures in this interpretative and reconstructive work.

This is therefore a twentieth-century reading, of a medieval manuscript, of a classical text – in which a body, or at least a body part, is in question.

References

Emile Benveniste, “Un emploi du nom du «genou» en vieil-irlandais et en sogdian”, Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris 27 (1), 1926, 51-53.

E. Benveniste, Textes Sogdiens: Édités, traduits et commentés, Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1940.

E. Benveniste, Vessantara Jātaka: Texte sogdien édité, traduit et commenté, Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1946.

Émile Benveniste, Études Sogdiennes, ed. Georges Redard, Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 1979.

Robert Gauthiot, “Une version sogdienne du Vessantara Jātaka: Publiée en transcription et avec traduction”, Journal Asiatique 19, 1912, 163-93 and 429-510; reprinted as Une version sogdienne du Vessantara Jātaka, Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1912.

K. Grønbech (ed.), Codices sogdiani: Manuscrits de la Bibliothèque nationale (Mission Pelliot) reproduits en fac-similé, introduction Emile Benveniste, Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1940.

Joseph Loth, “Le mot désignant le genou au sens de génération chez les Celtes, les Germains, les Slaves, les Assyriens”, Revue Celtique 40, 1923, 143- 52.

Joseph Vendryes, “Les correspondances de vocabulaire entre l’indo-iranien et l’italo-celtique”, Mémoires de la société linguistique de Paris XX, 1917, 265-85.

This is the seventeenth post of an occasional series, where I try to post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome.

The full list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Henry giving us a preview if his Plateaus reading as Nomad thought:

https://www.academia.edu/126196550/Plateau_3_The_Geology_of_Morals

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 27: more archive work on Saussure, Blanchot, Foucault, Jakobson and Koyré, two recordings, and a talk at the University at Buffalo | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 28: archives in Princeton, Chicago and final work in New York | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Sunday histories – short essays on Progressive Geographies | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Fifteen ‘Sunday Histories’ on Progressive Geographies | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: My publications in 2025 – on Koyré, Foucault, Lefebvre and some reviews | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: The French contributors to Herman Hirt’s 1936 Festschrift – Linguistics, Nationalism and Nazism | Progressive Geographies