The support for refugee scholars to come to the United States of America in the 1930s and 1940s is well known. Varian Fry famously helped several hundred European artists and intellectuals to flee Vichy France between 1940 and 1941. The Rockefeller Foundation also supported various academics, as did the Society for Protection of Science and Learning in the United Kingdom. I’ve done some work with these archives before. The records of the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars are at the New York Public Library, and there are some interesting stories to be told about their support.

The Emergency Committee operated between 1933 and 1945, initially focused on Jewish scholars in Germany, and then extending to other parts of Europe. It was originally called the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced German Scholars and changed its name in 1938. The funds were not given directly to the academics, but to universities or other places that would appoint them to positions, often as matching funds. In this way, universities could provide support to a displaced person, but have the benefit of appointing someone for a fraction of the usual cost, often in a temporary or entry-level post. The Emergency Committee supported Claude Lévi-Strauss, Ernst Kantorowicz, Alexandre Koyré, Jean Wahl and many others.

The Russian-born linguist Roman Jakobson had moved to Czechoslovakia in 1920, and taught mainly at the University of Brno, while also being a founding member of the Prague Linguistic Circle. He fled Czechoslovakia in March 1939, just as Germany invaded. He initially went to Denmark, then to Norway, and finally into Sweden. Stephen Rudy tells the story of crossing the Norwegian-Swedish border in a cart, with Jakobson in a coffin and his wife acting as the grieving widow (“Introduction”, x). Jakobson taught in all these Scandinavian countries, including general linguistics and Paleo-Siberian languages at the University of Oslo, and Russian at the University of Uppsala. He felt that the Nazis were following him from one refuge to another. In 1941 he boarded a ship to the United States, along with Ernst Cassirer and both of their wives. Jakobson taught at the École Libre des Hautes Études from 1942, at Columbia University from 1943, and later at Harvard University and MIT.

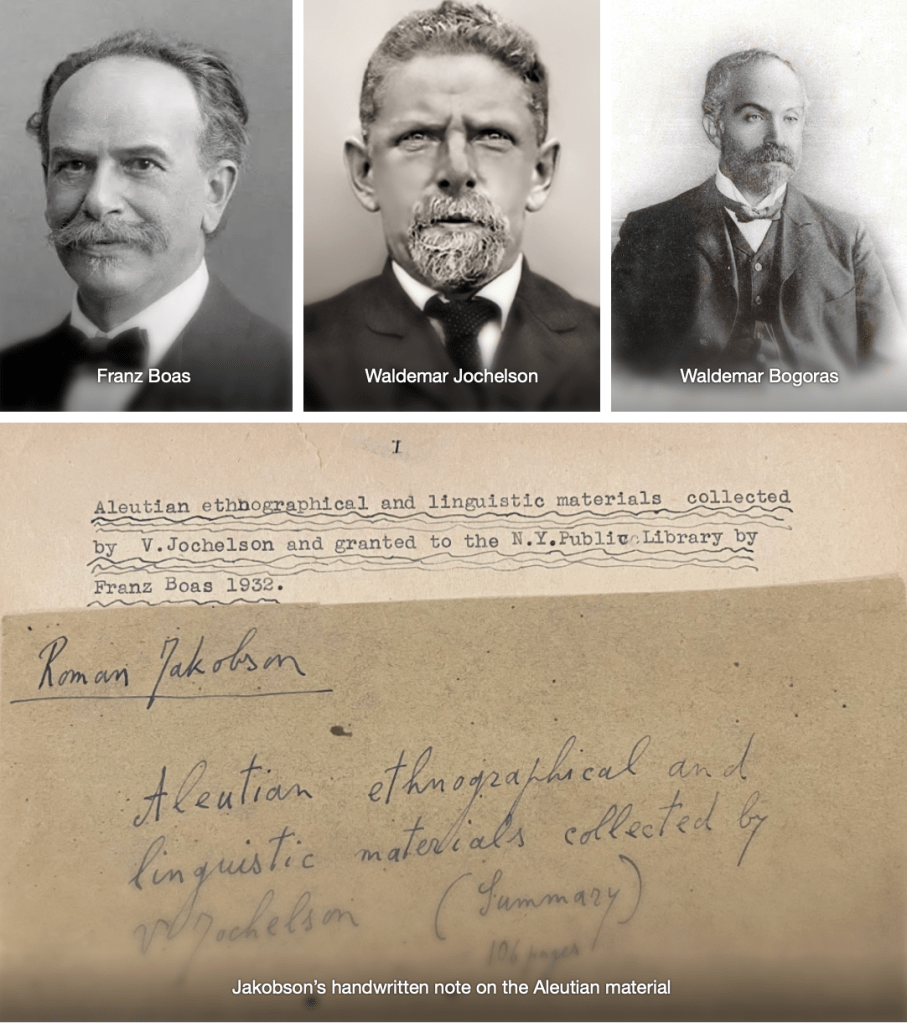

But his first work in the United States was a bit different than going straight into teaching. He worked for the New York Public Library (NYPL) on some Aleutian material collected by the anthropologist Franz Boas, and later on other languages spoken across eastern Siberia and Alaska. The work concerned collections originally made by Waldemar Jochelson in the Aleutian Islands and Kamchatka in 1909-10 for the Russian Geographical Society, and Waldemar Bogoras’s ethnographic papers from time in the northeast of Siberia in 1901. In June 1941 the NYPL asked the Emergency Committee if they could supplement the $50 per month they could afford to pay Jakobson in order for him to catalogue and organise the material. They said Jakobson’s specialism in East Siberian languages would make him well placed to work on these papers.

Although the initial reaction of the Emergency Committee was that support was unlikely, given the short-term nature of the contract, the committee members consulted were in favour. A note about Jakobson found in the Emergency Committee files shows that he was interviewed by a representative of the Committee. The report notes that he was “an earnest, consecrated, unworldly man – very absorbed in his work”. Matching funding was given, and Jakobson was employed for five months at $100 a month, although the decision was not approved until October 1941. He did not actually begin the work until 1 April 1942, and Boas was already concerned that these five months would be insufficient to complete the study. From correspondence quoted by his biographer Rosemary Lévy Zuwalt, it is clear that Boas was trying to find ways to support Jakobson: “He is a man of unusual knowledge and of great scientific attainment. I am seeing him often, and I have great respect for his knowledge and methods” (Boas to Alfred Louis Kroeber, 19 February 1942, cited in Franz Boas: Shaping Anthropology and Fostering Social Justice, 394; see also the letters in Swiggers, “Roman Jakobson’s Struggle in War-Time America”).

One letter from Jakobson indicates that he stayed at Boas’s home, and was doing some work for him on the links between Aleut and Gilyak before he was formally employed by the NYPL. Gilyak, also known as Nivkh, was spoken in Russia’s far east, in the area sometimes known as Russian Manchuria. In the letter, Jakobson says he was also doing research on the relatively unknown Yiddish-Czech language spoken by medieval Czech Jews, for the Yiddish Scientific Institute (YIVO), also in New York (Jakobson to Boas, 11 September 1941). He had met YIVO co-founder Max Weinrich in Copenhagen at the Fourth Congress of Linguistics in August 1936 (Jakobson to YIVO, 27 February 1969, Rachel Erlich papers, box 5). Some of Jakobson’s work for YIVO was published in “The City of Learning: The Flourishing Period of Jewish Culture in Medieval Prague” in The American Hebrew in December 1941. Jakobson there says he is “preparing a special detailed study about the ‘Canaan language’ in Jewish medieval culture” (p. 373). In a later piece he describes this as a book entitled Czech in Medieval Hebrew Sources (Selected Writings, Vol VI.2, 886). That study was never completed, though Jakobson did work on Canaanic (see Dittmann, “Roman Jakobson’s Research into Judeo-Czech”; Bláha et. al. “Roman Jakobson’s Unpublished Study on the Language of Canaanite Glosses”). He would also occasionally publish on Yiddish, writing a preface to Uriel Weinreich’s College Yiddish in 1949 (pp. 9-10). Uriel was the son of Max, with whom Jakobson would occasionally work. Jakobson and Morris Halle contributed to Max Weinreich’s Festschrift on “The Term ‘Canaan’ in Medieval Hebrew”. Although not published until 1964, this text was drafted in New York in 1942-44, before being completed in 1962 (see Selected Writings, Vol VI.2, 886).

Jakobson assimilated the material he was tasked with working on at the NYPL quickly into his previous knowledge. An earlier project with Nicolai Trubetzkoy, begun in the late 1920s, on the “Languages of the USSR” had been abandoned (see Nikolai Vakhtin, “Indigenous Minorities of Siberia and Russian Sociolinguistics of the 1920s”, especially 182-83; and Brandist, “Marxism and the Philosophy of Language in Russia in the 1920s and 1930s”). Jakobson published a survey on “The Paleosiberian Languages” in the American Anthropologist, which was published in the final issue of 1942. (This and “The City of Learning” were two of Jakobson’s very first publications in English; after previous publications in Russia, Czech, German and French.) Jakobson also began teaching at the École Libre in the 1942-43 academic year, in rooms provided by the New School. One of the first courses he led was a collaborative seminar on The Song of Igor, which led to the project I’ve discussed before – here and here.

This École Libre teaching was also supported by the Emergency Committee, who part-funded many of the French and Belgian academics who were teaching there. An application was also made to the Rockefeller Foundation to support Jakobson, but this was turned down. Noting this in his correspondence to the Emergency Committee, New School director Alvin Johnson said that his “own opinion of Jakobson is more favorable, perhaps because I have no bias against the Prague School of Philology. Jakobson seems to me an exceptionally brilliant scholar, and a most inspiring teacher” (5 October 1942). Writing in support of this application, the NYPL said that Jakobson “has just completed a study of Aleutian manuscript material from the point of view of language and folklore” (9 October 1942). The Emergency Committee supported his École Libre post with a grant of $1200, matched by the École Libre from other sources. The funding was renewed in subsequent years.

Boas died on 21 December 1942, and so did not live to see the results of the cataloguing work. Jakobson approached the NYPL and the Emergency Committee again in 1944 to ask if they would support him doing similar work on Kamchadal and ‘Asiatic Eskimo’ collections which Boas had given to him. (I am using ‘Eskimo’ as the historical term used to describe this material, as it appears in the letters and reports.) The Kamchadal materials were in the Jochelson papers; the Eskimo in the Bogoras papers. Jakobson told the NYPL and the Committee that Boas had wanted this material deposited in a library only after Jakobson had arranged and catalogued it. This support was given in June 1944, on the same terms as before – $250 from the Committee, with matching funds from the NYPL, for five months work, which began in the autumn.

Some parts of Jakobson’s cataloguing work were reported in two articles by Avrahm Yarmolinsky in the Bulletin of the New York Public Library in 1944 and 1947, both of which include material by Jakobson. Yarmolinksky was head of the Slavonic division of the NYPL from 1918-55. For the most part the two articles present folktales in English translations. The 1944 article has “A Note on Aleut Speech Sounds” by Jakobson and a bibliography he had prepared on Aleutian; the 1947 article a bibliography of work on Kamchadal and Eskimo. Jakobson’s work was described by Yarmolinksky as follows:

He corrected the summaries [of the folktales] and supplied them where they were lacking, and also classified the tales according to their dialect, literary style and subject-matter. Further, he added a note intended to clarify the phonology of the Eastern dialect of Aleut and simplify its transcription (“Aleutian Manuscript Collection”, pp. 671-72).

In 1944, Jakobson published an article on “Franz Boas’ Approach to Language”, written in tribute in summer 1943. He would write another tribute for the centenary of Boas’s birth in 1959.

Although Jakobson worked on many other topics, he did complete, or enable, some of these linguistic projects began during the War. In 1957, together with Gerta Hüttl-Folter and John Fred Beebe, Jakobson produced a two-hundred-page bibliographical guide to Paleosiberian Peoples and Languages. That year he also finally completed a study of the Gilyak language group, “Notes on Gilyak”, which he says he first began in Norway in 1939-40, worked on in Sweden in 1941, and discussed with Cassirer on the boat from Sweden to New York (see Selected Writings, Vol II, p. 97). Dean Stoddard Worth published the Kamchadal Texts Collected by Waldemar Jochelson in 1961. In his Introduction he thanks Jakobson: “at whose suggestion this work was begun, and thanks to whose constant help and advice it was finished” (p. 11).

In 1977 Robert Austerlitz surveyed Jakobson’s works on Paleosiberian languages, indicating the published materials, including the two notes in the Bulletin of the New York Public Library articles, and some unpublished conference papers, but not the manuscript material. He makes this point concerning the importance of Jakobson’s work in this area: “In sum, then, the Paleosiberian field has benefited from Jakobson the theoretician and general linguistics from Jakobson the Paleosiberianist” (p. 18).

Finally, in 2023, Nikolai B. Vakhtin published most of Jakobson’s report on the Jochelson material. The article discussing the work is in Russian, but the report is reproduced in English. Vakhtin includes the introduction, the notes on dialectic and motifs, and the grammar, but only a few of the notes on the individual folktales. The part which Yarmolinsky published on the phonology of the languages is shown to have been edited by him, and Vakhtin publishes Jakobson’s original text. As far as I know, the briefer reports Jakobson made on the Kamchadal and Eskimo material have not been published. Reading them gives a clear sense of how Jakobson was able to engage with so many different researchers, from linguistics to literature, to anthropology and mythology. All these reports, and the material they are cataloguing, are in the New York Public Library archives.

References

Robert Austerlitz, “The Study of Paleosiberian Languages” in Daniel Armstrong and C. H. van Schooneveld (eds.). Roman Jakobson: Echoes of his Scholarship, Lisse: Peter de Ridder, 1977, 13–20.

Ondřej Bláha, Robert Dittmann, Karel Komárek, Daniel Polakovič and Lenka Uličná, “Roman Jakobson’s Unpublished Study on the Language of Canaanite Glosses”, Jews and Slavs 24, 2012, 282-318.

Jonathan Bolton, “Jakobson, Roman Osipovich”, The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, https://encyclopedia.yivo.org/article/411

Craig Brandist, “Marxism and the Philosophy of Language in Russia in the 1920s and 1930s”, Historical Materialism 13 (1), 2005, 63-84.

Robert Dittmann, “Roman Jakobson’s Research into Judeo-Czech”, in Tomáš Kubíček and Andrew Lass eds. Roman O. Jakobson: A Work in Progress, Olomouc: Palacký University, 2014, 145-53.

Murray B. Emeneau, “Franz Boas as a Linguist”, American Anthropologist 45 (3) part 2, 1943, 35-38 (No 61 of Memoir Series of the American Anthropological Association, “Franz Boas, 1858-1942”).

Roman Jakobson, “The City of Learning: The Flourishing Period of Jewish Culture in Medieval Prague” [1941], reprinted in Selected Writings, Vol IX.2, 371-79.

Roman Jakobson, “The Paleosiberian Languages”, American Anthropologist 44 (4), 1942, 602-20, reprinted in Selected Writings, Vol IX.2, 385-407.

Roman Jakobson, “Franz Boas’ Approach to Language”, International Journal of American Linguistics 10 (4), 1944, 188-95, reprinted in Selected Writings, Vol II, 477-88.

Roman Jakobson, “Notes on Gilyak” [1957], reprinted in Selected Writings, Vol II, 72-97.

Roman Jakobson, “Boas’ View of Grammatical Meaning” [1959], reprinted in Selected Writings, Vol II, 489-96.

Roman Jakobson, Selected Writings, The Hague: Mouton & Co, nine volumes, 1962-

Roman Jakobson and Morris Halle, “The Term ‘Canaan’ in Medieval Hebrew” [1964], reprinted in Selected Writings, Vol VI.2, 858-86.

Roman Jakobson, Gerta Hüttl-Folter and John Fred Beebe, Paleosiberian Peoples and Languages: A Bibliographical Guide, New Haven: HRAF Press, 1957.

Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt, Franz Boas: The Emergence of the Anthropologist, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019.

Rosemary Lévy Zumwalt, Franz Boas: Shaping Anthropology and Fostering Social Justice, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2022.

Stephen Rudy, “Introduction”, in Roman Jakobson, My Futurist Years, ed. Bengt Jangfeldt and Stephen Rudy, New York: Marsilio, 1997, ix-xxvi.

Dean Stoddard Worth, Kamchadal Texts Collected by Waldemar Jochelson, The Hague: Mouton, 1961.

Pierre Swiggers, “Roman Jakobson’s Struggle in War-Time America: More Epistolary Testimonies”, Orbis 36, 1993, 281-85.

Nikolai Vakhtin, “Indigenous Minorities of Siberia and Russian Sociolinguistics of the 1920s: A Life Apart?”, Acta Borealia 32 (2), 2015, 171-89.

Nikolai B. Vakhtin, “Roman Jakobson and the Aleut Materials Collected by Waldemar Jochelson”, Voprosy Jazykoznanija 4, 2023, pp. 117-28, doi: 10.31857/0373-658X.2023.4.117-128

Uriel Weinreich, College Yiddish, New York: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 1974 [1949].

Avrahm Yarmolinsky, “Aleutian Manuscript Collection”, Bulletin of the New York Public Library, 48 (8), 1944, 671-80.

Avrahm Yarmolinsky, “Kamchadal and Asiatic Eskimo Manuscript Collections: A Recent Accession”, Bulletin of the New York Public Library 51(11), 1947, 659-69.

Archives

Franz Boas papers, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia,https://as.amphilsoc.org/repositories/2/resources/852

Waldemar Bogoras papers, MssCol 328, New York Public Library, https://archives.nypl.org/mss/328

Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars records, MssCol 922, New York Public Library, https://archives.nypl.org/mss/922

Rachel (Shoshke) Erlich papers, 1934-1984, RG 1300, YIVO archives, Center for Jewish History, New York, https://archives.cjh.org/repositories/7/resources/22118

Roman Jakobson papers, MC-0072, Department of Distinctive Collections, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, https://archivesspace.mit.edu/repositories/2/resources/633

Waldemar Jochelson papers 1909-1937, MssCol 1565, New York Public Library, https://archives.nypl.org/mss/1565

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Ondřej Bláha and Pierre Swiggers for sharing hard-to-find publications; and the archives listed above for access to materials.

This is the twenty-second post of a weekly series, where I post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome.

The full list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Sunday histories – short essays on Progressive Geographies | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 28: archives in Princeton, Chicago and final work in New York | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 29: working on Benveniste’s Vocabulaire, Dumézil’s Bilan and other work | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Roman Jakobson’s paper to The First World Conference on Yiddish Studies, 1958: “The Languages of the Diaspora as a Particular Linguistic Problem” | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Vladimir Nabokov’s original and unpublished translation of The Discourse of Igor’s Campaign; and Roman Jakobson’s enduring wish to complete his English edition | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Vladimir Nabokov’s original and unpublished translation of The Discourse of Igor’s Campaign; and Roman Jakobson’s enduring wish to complete his English edition | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Gordon and Tina Wasson, Slavic Studies in the Cold War, and the Hallucinogenic Mushroom | Progressive Geographies