The 18-21 October 1966 Baltimore conference on structuralism has long been recognised as important for the reception of French theory in the United States. Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Lucien Goldmann, Jean Hyppolite, Jacques Lacan and Jean-Pierre Vernant were some of the French theorists brought to Johns Hopkins University for the event. Fernand Braudel and Claude Lévi-Strauss were involved in the planning but did not attend. Peter Caws, Paul de Man, Tzvetan Todorov, and Edward Said attended. Roman Jakobson was in Europe at the time, so could not be there. Michel Foucault was apparently invited, but didn’t attend. Derrida’s closing paper, “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences”, is the most famous talk, not least for being a fundamental disruption of structuralism, almost as soon as it had arrived. He was a late addition to the lineup.

The conference was organised by René Girard, Richard Macksey, and Eugenio Donato. The story of the event is well told in Chapter 8 of Cynthia L. Haven’s biography of Girard, Evolution of Desire, based on conversations with Macksey and Girard. That’s worth a read just for a sense of Lacan’s prima-donna behaviour – his laundry demands, his underprepared paper, and his huge hotel phone bill. The editors of the proceedings remark that Lacan “chose to deliver his communication alternately in English and French (and at points in a composite of the two languages), this text represents an edited transcription and paraphrase of his address” (The Structuralist Controversy, p. 186 n. 1). Macksey recalls that Anthony Wilden had “the challenging role of serving night and day as Dr. Lacan’s cicerone, valet, and amanuensis” (“Anniversary Reflections”, p. xiv). Presumably because of jetlag, Lacan was awake at dawn, and incorporated this into his paper:

When I prepared this little talk for you, it was early in the morning. I could see Baltimore through the window and it was a very interesting moment because it was not quite daylight and a neon sign indicated to me every minute the change of time, and naturally there was heavy traffic and I remarked to myself that exactly all that I could see, except for some trees in the distance, was the result of thoughts actively thinking thoughts, where the function played by the subjects was not completely obvious. In any case the so-called Dasein as a definition of the subject, was there in this rather intermittent or fading spectator. The best image to sum up the unconscious is Baltimore in the early morning (The Structuralist Controversy, p. 189).

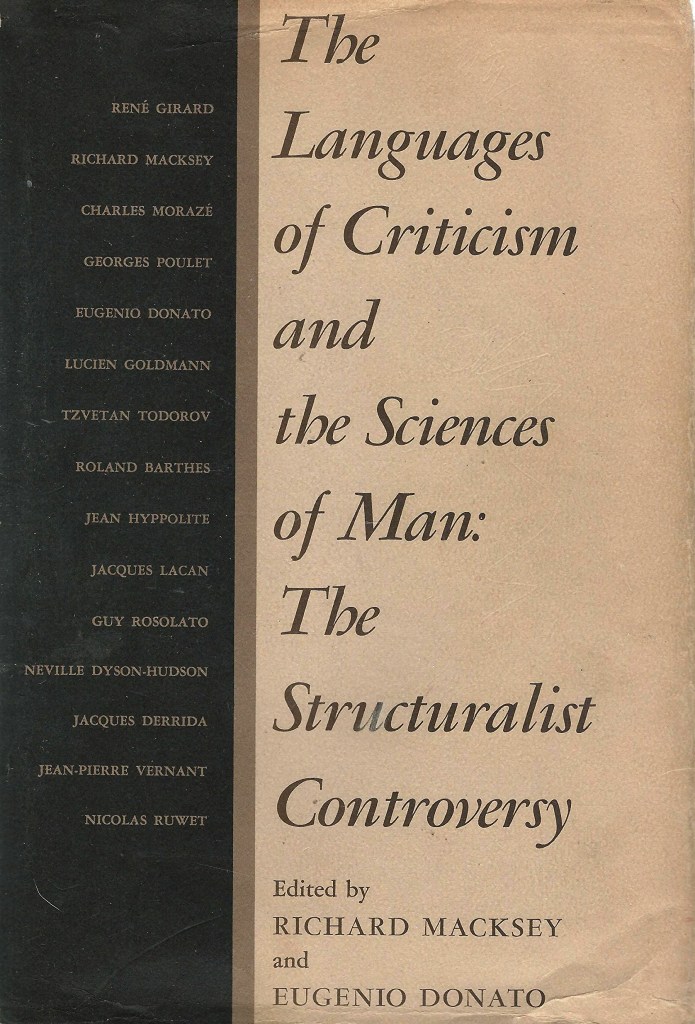

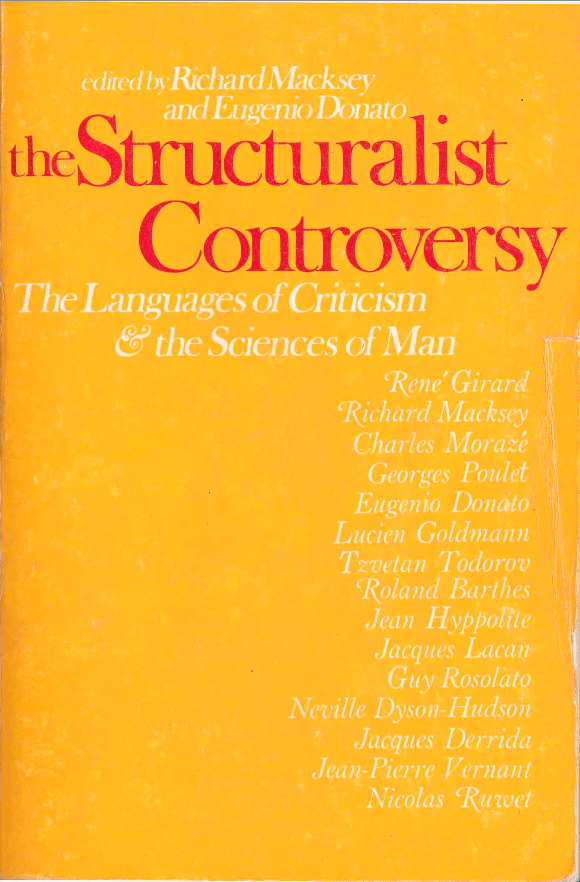

The event was generously funded by the Ford Foundation – “just enough gunpowder to make the cannon go off” (Macksey, quoted by Haven, Evolution of Desire, p. 123) – and led to seminars over a two-year period. After the event, Girard left the editing work to his younger colleagues: only Donato and Macksey appear as editors of 1970 book The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man, though Girard’s paper and concluding remarks to the conference are included. The book was dedicated to “the memory of Jean Hyppolite—scholar, teacher and friend of scholars” (p. v), who died in 1968. The paperback edition of 1972 has its better-known title of The Structuralist Controversy, the original book’s subtitle. (That edition has a brief new preface, and a bibliographical note, but removes the French texts of Goldman, Hyppolite and Vernant in the appendix.) A fortieth-anniversary edition appeared in 2017, which is quite funny, because it shows how academics always miss deadlines: a fortieth anniversary of the book would have been 2010. Perhaps they should have commemorated fifty years of the event, and only been late by a year. The editors thank Sally Donato and Catherine Macksey, and Nancy Gallienne of The Johns Hopkins University Press, but they are the only women who seem to have been involved in the event or book (p. xix).

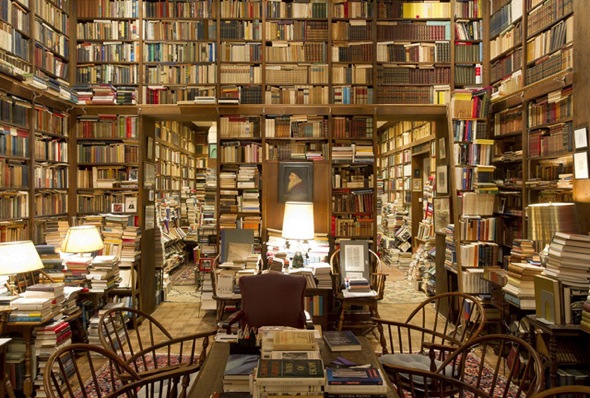

Girard is well-known, and Macksay had a profile in Literary Hub, while images of his crammed personal library regularly circulate online (see here and here). The third name has not had the same attention. Haven describes him as “that brilliant figure who has been somewhat overlooked in American intellectual history—the restless, quicksilver Eugenio Donato” (p. 122). Donato had received his doctorate in 1965 from Johns Hopkins University, where he was advised by Girard. He taught at Cornell University (1963-64), Johns Hopkins (1964-68), State University of New York at Buffalo (1968-76) and ended his career at the University of California, Irvine (1976-83). He was Professor of French and Comparative Literature at Buffalo when Foucault visited in 1970 and 1972, a visit mediated by Girard. Donato had followed Girard to Buffalo, part of what Haven calls a “long and tempestuous relationship” (p. 144).

Donato died at the age of just 46 in 1983. Macksey wrote a short tribute for MLN, a journal in which Donato had published much of his work. The following year, Donato’s former PhD researcher, Josué Harari, on whom I’ve written before in relation to Foucault and Sade, led a tribute issue of MLN for him. It appeared as the French Issue, Vol 99 No 4. As well as Harari’s brief tribute and a longer essay by him, it included pieces by Derrida, Girard, Macksey and Said. The issue was bookended by two essays by Donato, “Who Signs Flaubert?” and “The Writ of the Eye”. The first was an English version of a text he had published in the journal in French shortly before he died; the second an unpublished text discovered after Donato’s death.

In the fortieth anniversary reflections of The Structuralist Controversy, Macksey says:

This is also an opportunity to salute the memory of Eugenio Donato (1937-83). One of the youngest participants in the symposium (two years younger than Edward Said, among the colloquists), the vector of his career was already established by the time of these meetings. He had instituted seminars on Lévi-Strauss, Lacan, Barthes, and other players in the structuralist drama; had stimulated colleagues; and inspired students. With his too-early death we lost a generous friend, a vital animator of debates, and a pioneer in critical exchange. Here as elsewhere he was instrumental in bringing Continental theory and American critical practice into an active dialogue. The force of his personality played a vital role in teaching many on this side of the Atlantic how to read critically and in showing their European colleagues how to listen sympathetically (p. xiii).

Donato knew Foucault’s 1970 lectures at Buffalo, which included a discussion of Flaubert. The notes for that lecture are included in Madness, Language, Literature. Like Harari and Sade, Donato and Flaubert is another indication of the interest Foucault’s lectures would have had for his audience. Although Donato does not reference Foucault in “Who Signs Flaubert?”, the essay develops two themes from his visit. First, it situates Flaubert’s work between The Temptation of St Antony and the unfinished Bouvard and Pécuchet, the two books Foucault had concentrated on in his Buffalo lecture, rather than the more famous Madame Bovary or Sentimental Education. Second, it has a sustained analysis of the authorial status of ‘Flaubert’ – Foucault had given a version of “What is an Author?” in Buffalo.

A decade after his death, Donato’s work was compiled into The Script of Decadence: Essays on the Fictions of Flaubert and the Poetics of Romanticism, published by Oxford University Press. This text includes “Who Signs Flaubert?” The other essays reference Foucault in several places, both his essay on Flaubert and The Order of Things. The book contains detailed discussions of Bouvard and Pécuchet and The Temptation of St Anthony(Chs. 3 and 4), which he privileges, suggesting they challenge the idea of Flaubert as a realist (pp. 36, 103). He reads Bouvard and Pécuchet in relation to the encyclopaedic aspirations of the protagonists, and Flaubert’s own comments about the way he composed the work. It is a book made from fragments of other books, “the metaphor of the Encyclopedia-Library”. In this reading Donato stresses that Foucault and Hugh Kenner were following Jean Seznec, “but without acknowledging him” (p. 57), and he recognises the limitations of this approach to the novel (pp. 59-60). Donato also criticises the archaeological metaphors of Foucault’s work of the late 1960s (p. 66). Unlike Foucault, he also discusses Salammbô in detail (Ch. 2). This chapter, first published in 1976, predates Edward Said’s discussion of this text in Orientalism, and forms an interesting complement to that reading.

In 2023, recordings of the 1966 Baltimore conference were made available online, with transcriptions of some of the talks, including the ones by Jean-Pierre Vernant and Jacques Derrida. In the preface, the editors had noted that the book had been edited from “some thirty hours of tapes” (p. xvii). The tapes were eventually found in Macksey’s home library. Johns Hopkins librarian Liz Mengel describes the discovery: “They were hidden in a cabinet behind a bookshelf behind a couch” (quoted by Dwyer). Derrida’s lecture differs from the published version, and includes more of the discussion after his lecture. Lacan’s “Of Structure as an Inmixing of an Otherness Prerequisite to Any Subject Whatever” paper is more amusing as a recording than on the page.

As early as 1973 Donato was suggesting that:

Structuralism as a critical concept has outlived its usefulness. It should not be long before it finds its rightful place in textbooks of philosophy or cultural history. Few will miss its disappearance. If the works of Foucault and Derrida are a sign of things to come, a new problematic remains to be developed with Nietzsche at the center, occupying the place that Hegel occupied when existentialism and structuralism ran their course (p. 25).

This was just a year after the paperback of The Structuralist Controversy, and two years after Josué Harari’s reading guide, Structuralists and Structuralisms: A Selected Bibliography of French Contemporary Thought (1960-1970), dedicated to Donato and Girard. As I’ve noted before, following Jonathan Culler, many of the figures included in this bibliography reappear in Harari’s 1979 collection Textual Strategies, whose subtitle is Perspectives in Post-Structuralist Criticism. As has often been suggested, Derrida’s closing lecture to the 1966 conference is one moment in the shift from structuralism to what is sometimes called post-structuralism. Given that this designation is an American label, Harari and Donato are significant figures in its shaping.

Another important moment would be the 1978 boundary 2 conference published in 1982 as The Question of Textuality: Strategies of Reading in Contemporary American Criticism, edited by William V. Spanos, Daniel O’Hara and Paul Bové. Several key figures from this set of debates presented, including Said and Donato, who also had an exchange after their papers, as well as David Allison, Jonathan Arac, Joseph Buttigieg, David Couzens Hoy, Jonathan Culler, Stanley Fish, Murray Krieger, Marie-Rose Logan and Mark Poster. Again, it’s a very male line-up, with the exception of Logan. Perhaps that collection deserves a separate post.

References

Jonathan Culler, “1980: Structuralism and Poststructuralism”, Ex-position 40, 2018, 79-94.

Jacques Derrida, “An Idea of Flaubert: ‘Plato’s Letter’”, trans. Peter Starr, MLN 99 (4), 1984, 748-68.

Eugenio Donato, “Structuralism: The Aftermath”, SubStance 3 (7), 1973, 9-26.

Eugenio Donato, “Flaubert and the Question of History: Notes for a Critical Anthology”, MLN 91 (5), 1976, 850-70; reprinted in The Script of Decadence: Essays on the Fictions of Flaubert and the Poetics of Romanticism, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, Ch. 2.

Eugenio Donato, “Qui Signe ‘Flaubert’?”, MLN 98 (4), 1983, 579-93; “Who Signs Flaubert?” MLN 99 (4), 1984, 711-26; English reprinted in The Script of Decadence: Essays on the Fictions of Flaubert and the Poetics of Romanticism, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, Ch. 5.

Eugenio Donato, “The Writ of the Eye: Notes on the Relationship of Language to Vision in Critical Theory”, MLN 99 (4), 1984, 959-78.

Eugenio Donato, The Script of Decadence: Essays on the Fictions of Flaubert and the Poetics of Romanticism, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Kate Dwyer, “Meet the Man who Introduced Jacques Derrida to America”, Literary Hub, 6 December 2018, https://lithub.com/meet-the-man-who-introduced-derrida-to-america/

Kate Dwyer, “A Library the Internet Can’t Get Enough Of: Why does this image keep resurfacing on social media?”, The New York Times, 16 January 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/15/style/richard-macksey-library.html

Stuart Elden, The Archaeology of Foucault, Cambridge: Polity, 2023.

Michel Foucault, “Postface à Flaubert (G.) Die Versuchung des Heiligen Antonius (La Tentation de saint Antoine)”, Dits et écrits 1954-1988, eds. Daniel Defert and François Ewald, Paris: Gallimard, four volumes, 1994, Vol I, 293-325 (comparative edition of the 1967 and 1970 French texts); “Afterword to The Temptation of Saint Anthony”, Essential Works Volume Two: Aesthetics, Method and Epistemology, ed. James D. Faubion, New York: The New Press, 1998, 103-22 (translation of the 1967 text).

Michel Foucault, Folie, langage, littérature, ed. Henri-Paul Fruchaud, Daniele Lorenzini and Judith Revel, Paris: Vrin, 2019; Madness, Language, Literature, trans. Robert Bononno, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023.

René Girard, “Dionysus versus the Crucified”, MLN 99 (4), 1984, 816-35.

Josué V. Harari, Structuralists and Structuralisms: A Selected Bibliography of French Contemporary Thought (1960-1970), Ithaca: Diacritics, 1971.

J.V. Harari ed., Textual Strategies: Perspectives in Post-Structuralist Criticism, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1979.

Josué Harari, “In Memorium: Eugenio Donato 1937-1983”, MLN 99 (4), 1984, 709-10.

Josué Harari, “Dream Objects”, MLN 99 (4), 1984, 836-44.

Cynthia L. Haven, Evolution of Desire: A Life of René Girard, East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2018.

Cynthia L. Haven, “A Legendary Library goes Viral!”, The Book Haven, 18 January 2022, https://bookhaven.stanford.edu/2022/01/dick-mackseys-library-goes-viral/

Judd Hubert, John Rowe and Franco Tonelli, “Eugenio Donato, French and Italian: Irvine”, University of California: In Memoriam, http://texts.cdlib.org/view?docId=hb4d5nb20m;NAAN=13030&doc.view=frames&chunk.id=div00045&toc.depth=1&toc.id=&brand=oac4

Richard Macksey, “In Memorium: Eugenio Donato (1937-1983)”, MLN 98 (5), 1983, 1381-82.

Richard Macksey, “Keats and the Poetics of Extremity”, MLN 99 (4), 1984, 845-84.

Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato (eds.), The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man: The Structuralist Controversy, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1970.

Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato (eds.), The Structuralist Controversy: The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1972; 40th anniversary edition 2017.

Richard Macksey, “Anniversary Reflections”, in Richard Macksey and Eugenio Donato (eds.), The Structuralist Controversy: The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017, ix-xiv.

Edward W. Said, “The Future of Criticism”, MLN 99 (4), 1984, 951-58; reprinted in Reflections on Exile and Other Literary and Cultural Essays, London: Granta, 2000, Ch. 16.

William V. Spanos, Paul A. Bové and Daniel O’Hara (eds.), The Question of Textuality: Strategies of Reading in Contemporary American Criticism, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1982.

Mack Zalin, “Recordings and Transcriptions of the ‘The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man’”, The Sheridan Libraries & University Museums Blog, 14 March 2023, https://blogs.library.jhu.edu/2023/03/recordings-and-transcriptions-of-the-the-languages-of-criticism-and-the-sciences-of-man/

Archives

Donato (Eugenio) papers, MS.C.009, University of California, Irvine, Critical Theory, Irvine, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt838nf5vz/

Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man conference recordings, 18-21 October 1966, Johns Hopkins University archives, https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/66881

Marli Shoop Audio Recordings of Eugenio Donato and Wolfgang Iser Lectures MS.C.022, University of California, Irvine, Critical Theory, Irvine, https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c86d5rcf/

Richard Macksey papers, MS-0907, Johns Hopkins University archives, https://aspace.library.jhu.edu/repositories/3/resources/1555

This is the twenty-seventh post of a weekly series, where I post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome.

The full list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here.

Discover more from Progressive Geographies

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: Josué V. Harari, the Marquis de Sade, and Michel Foucault’s 1970 lectures in Buffalo | Progressive Geographies

There is a poem by David Kirby, that mentions this conference (I think). It’s titled ‘Dear Derrida’ published in 2000.

‘That year magi appeared from the east:

Jacques Lacan, Tzvetan Todorov,

Roland Barthes, and Jacques Derrida

brought their Saussurean strategies

to the Hopkins conference on “The Language

of Criticism and the Sciences of Man,”’

Accessible via this link: http://storysouth.com/stories/dear-derrida/

Pingback: Indo-European Thought in Twentieth-Century France update 29: working on Benveniste’s Vocabulaire, Dumézil’s Bilan and other work | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Glyph: Johns Hopkins Textual Studies – Samuel Weber, Deconstruction and the American Reception of French Theory | Progressive Geographies

Pingback: Did Benveniste read Derrida’s Of Grammatology? | Progressive Geographies