In Birth of the Clinic, Foucault quotes a passage which he incorrectly references to “S.A.D. Tissot, Avis aux gens de lettres sur leur santé, Lausanne, 1767, p. 28”. As part of the work for the new translation and edition of this text, we are checking, completing and correcting all of Foucault’s references. There are enough errors to make this worthwhile, if very time-consuming, work. Fortunately, we have the help of Noah Delorme. In this instance, Noah indicated that the passage quoted by Foucault is not found in Tissot’s book.

The following footnote is to “ibid, p. 28”, and that quotation is found on that page of Tissot’s work – its full title is Avis aux gens de lettres et aux personnes sédentaires sur leur santé. I think Foucault typed up a messy handwritten manuscript, read the first reference as the second, and then on moving to the second note, thought it was in the same place.

The passage in question reads, in the quotation by Foucault:

Les médecins doivent se borner à connaître les forces des médicaments et des maladies au moyen de leurs opérations ; ils doivent les observer avec soin et s’étudier à en connaître les lois, et ne point se fatigue à la recherche des causes physiques (Naissance de la clinique, 1st edition, p. 12; 2nd edition, p. 12; Quadrige edition, p. 33).

Alan Sheridan translates this as:

Physicians must confine themselves to knowing the forces of medicines and diseases by means of their operations; they must observe them with care and strive to know their laws, and be tireless in the search for physical causes (The Birth of the Clinic, p. 13).

Sheridan simply copies Foucault’s erroneous note (The Birth of the Clinic, p. 20 n. 20).

Where, then, is the passage Foucault quotes actually from? Simple searching with a string of words from the quote usually led to online versions of Foucault’s text, but I eventually found it was also referenced in Théophile Roussel, De la valeur des signes physiques dans les maladie du coeur, 1847, p. 70. The text has some slight differences from Foucault’s quotation, but it’s certainly the same passage. Roussel indicates that it comes from “Pitcairn”. No page, no work referenced. This is Archibald Pitcairn, sometimes spelled Pitcairne, a Scottish physician from the 17th century. But he wrote in Latin and English, so finding the exact passage when what we have is a French translation of a quotation (and an English translation of that French) was going to be difficult.

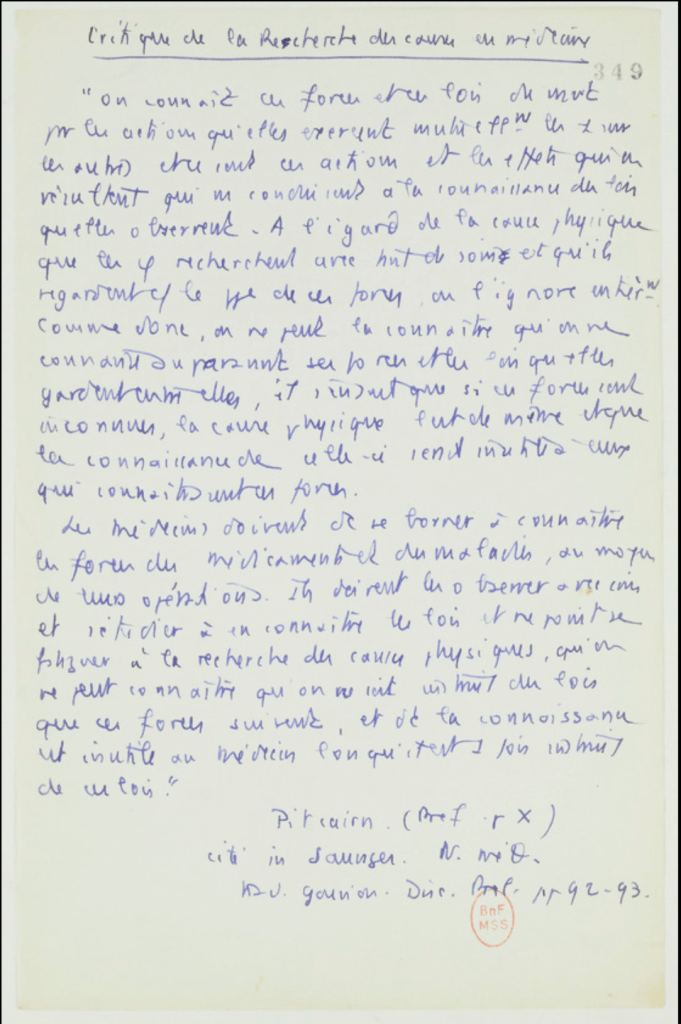

Most of Foucault’s preparatory notes for his books, but not the manuscripts, are digitised on the Fiches de lecture site. Searching for “Pitcairn” gave no hits, and “Roussel” only pointed to Raymond Roussel, the writer on whom Foucault wrote a book. My own notes from Foucault’s archive – before any of this was digitised – indicated that on one sheet of his preparatory notes Foucault wrote down a quotation from Pitcairn, cited in Boissier de Sauvages, Nosologie methodique, Vol I, pp. 92-93. I didn’t copy the passage, but just noted the reference.

Boissier de Sauvages is someone Foucault uses a lot in Birth of the Clinic, but my notes on where it was in his archive then enabled me to locate the page in the Fiches de lecture. If you are curious to see a page of Foucault’s notes, it is here. Sure enough, this copies a longer passage which was the source of the quotation in Foucault’s book.

Foucault indicates the reference on that sheet as “Pitcairn (Préf, p. x) cité in Sauvages, N. méq. Trad Gouvion, Disc. Prel. pp. 92-93”. That’s the “Discours préliminaire” in Boissier de Sauvages, Nosologie methodique, and the passage Foucault copies down is indeed on those pages. The book is scanned on archive.org and the quotation Foucault uses is on p. 93.

Les Médecins doivent donc fe borner à connoître les forces des médicamens & des maladies au moyen de leurs opérations ; ils doivent les obferver avec foin , & s’étudier à en connoître les lois, & ne point fe fatiguer à la recherche des caufes phyfiques, qu’on ne peut connoître qu’on ne foit inftruit des lois que ces forces fuivent, & dont la conoiffance eft inutile au Médecin, lorfqu’il eft une fois inftruit de ces lois. Pitcairn. Préf. Pag. x.

The typography explains why it’s not easy to locate by a simple search, with the use of the long s, ſ, which appears as ‘f’ above, and the spelling of connaître and connaissance with an ‘o’. This is undoubtedly Foucault’s source for the passage in Birth of the Clinic, and his note should therefore have read “Pitcairn, p. x, cited in Sauvages… p. 93”. The preceding note by Foucault is to that same work by Sauvages, pp. 91-92. It’s sloppy certainly, but not difficult to see how he messed up his references when typing up the text, or when hand-copying an earlier draft.

Of course, Foucault’s book has gone through reprints as well as the previous translation, but this error hasn’t been noticed by the publisher or translator before. The exception is in the edition of Naissance de la Clinique in the Pléiade Œuvres, François Delaporte corrected the note to read “Ibid, p. [93]”, which accurately points the reader to the correct page of Sauvages, but makes it seem like the passage was Sauvages’s words, not those of Pitcairn. But Delaporte’s amended note means that in future, checking Œuvres might save us some time.

What work was this by Pitcairn? Sauvages wrote in Latin, with the text Foucault is referencing a French translation by Gouvion. The indicate of “Préf” misled me, as I was thinking it was a preface to a book. Eventually, I found the passage was in Pitcairne’s inaugural lecture for his chair in Leiden. The Oratio was given in Latin and is in his Opuscula medica – it’s available online from the Wellcome Collection. I’ve amended the ‘ſ’ to ‘s’ in this passage, but otherwise the spelling is as the original.

adeque Medicis incumbit solùm, ut Vires Medicamentorum & Morborum, qua per Operationes possunt inveniri, expendant, & ad Leges revocent ; non autem, ut Causis physicis eruendis insudent, quæ non nisi ex prius inventis Virium Legibus possunt deduci, iifque inventis Medico non sunt profuturæ (p. 4).

In the 1695 separate printing of the Oratio the passage is on p. 11. I then found an English version in The Works of Archibald Pitcairn from 1715, on archive.org (again amending the ‘ſ’ to ‘s’):

And therefore the Business of a Physician is to weigh and consider the Powers of Medicines and Diseases as far as they are discoverable by their Operations, and to reduce them to Laws ; and not lay out their Time and Pains in searching after Physical Causes, which can never be deduced till after the Laws of their Powers are found out ; and when they are found out, will be of no Service to a Physician (p. 12).

The Oratio is the first text in the works, and so it does serve as a kind of preface to the other writings, which is presumably what Sauvages’s reference means. In the 1727 and 1740 editions of The Whole Works the passage is on p. 10. So, we have a Latin text, with an authorised English version, quoted by Sauvages, who is translated into French, which is quoted by Foucault, who made a right mess of the reference, which was then translated by Sheridan, who copied the reference. For over sixty years this has remained uncorrected, with Delaporte only doing part of the work for this note in the Œuvres.

While having access to many of these works online is invaluable, simply searching for the string of words didn’t solve the problem. Sauvages references this to p. x, which is presumably an edition I’ve not yet seen – the English editions I’ve seen are either p. 12 or p. 10, and the Latin p. 11 or p. 4 – but otherwise this is resolved. We will provide the correct reference in the new edition, but not show all the work it took to get there…

Foucault’s reference to S.A.D. Tissot, Avis aux gens de lettres sur leur santé, Lausanne, 1767, p. 28 is incorrect. The passage is found in Archibald Pitcairn, Opuscula medica: Quorum multa nunc primum prodeunt, Rotterdam: Fritsch & Böhm, 1714, p. 4; Archibald Pitcairn, The Works of Dr. Archibald Pitcairn…, London: E. Curll, J. Pemberton and W. Taylor, 1715, p. 12; cited in Boissier de Sauvages, Nosologie méthodique, p. 93.

References

Boissier de Sauvages, Nosologie méthodique ou distribution des maladies, trans. M. Gouvion, Lyon: Jean-Marie Bruyset, 1772.

Michel Foucault, Naissance de la clinique: Une archéologie du regard medical, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France,1963, revised edition 1972; The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception, trans. A.M. Sheridan, London: Tavistock, 1973.

Michel Foucault, Œuvres, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, ed. Frédéric Gros, Paris: Gallimard, 2 vols, 2015.

Archibald Pitcairn, Opuscula medica: Quorum multa nunc primum prodeunt, Rotterdam: Fritsch & Böhm, 1714.

Archibald Pitcairn, The Works of Dr. Archibald Pitcairn; wherein are discovered the true foundation and principles of the art of physic: with cases and observations upon most distempers and medicines. Done from the Latin original. There is also added, his method of curing the small-pox, London: E. Curll, J. Pemberton and W. Taylor, 1715.

Théophile Roussel, De la valeur des signes physiques dans les maladie du coeur, Paris: Pierre Baudouin, 1847.

S.A.D. Tissot, Avis aux gens de lettres et aux personnes sédentaires sur leur santé, Paris: J. Th. Herissant Fils, 1767.

This is the 51st post of a weekly series, where I post short essays with some indications of further reading and sources, but which are not as formal as something I’d try to publish more conventionally. They are usually tangential to my main writing focus, a home for spare ideas, asides, dead-ends and possible futures. I hope there is some interest in them. They are provisional and suggestions are welcome. A few, usually shorter, pieces in a similar style have been posted mid-week.

The full chronological list of ‘Sunday histories’ is here, with a thematic ordering here.