After a book manuscript is delivered to a publisher, and agreed in final form, a whole lot of things happen. This is one of those ‘black boxes’ in publishing, and some thoughts might be of interest. What follows is a description of the stages in the period sometimes described as ‘in press’, that is, no longer ‘under review’, but not yet available in bookshops or online. Bear in mind these are my experiences, albeit across a reasonable range of publishers, with authored and edited books. I’ve tended to work with publishers again if I’ve had a good experience, or aspire to do so (University of Chicago Press is a good example of the latter). Some of these comments are quite critical, but there is much here I wish I’d known earlier in my career.

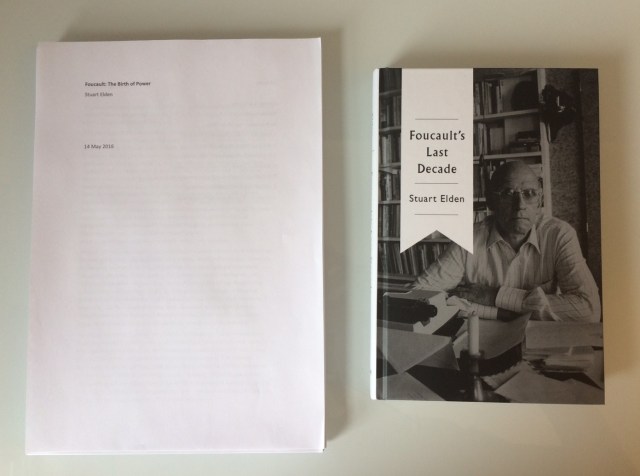

A just-completed manuscript and a just-published book

Title – strangely, many contracts only give the book a provisional title, and then the title is agreed after the manuscript is in production. This seems wrong-headed to me. I accept that people other than the author should have a say in the title, but when that is can be an issue. A book’s text should reflect the title, as well as the other way round. If the title changes, parts of the book may need to be rewritten. So I’ve tried to insist on the title being discussed and agreed earlier in the process, but that’s easier when you are further ahead in your career and can afford to be bullish. When it comes to deciding titles, publishers want the keywords right up front, they will often switch subtitles and titles, they don’t like specialised language, and pleading of ‘nobody who has read the book could think that is an appropriate title’ won’t work (this is marketing, remember).

Cover – this may have been agreed beforehand, but frequently not. And presses will come up with all sorts of strange ideas of what looks good. Often authors are given input into the process; sometimes they are even listened to. When I’ve done workshops on publishing I’ve often said that authors tend to lose two battles with publishers – over the title and the cover. I think there is a lot in that. It has, at least for me, got easier as I’ve got more senior, but I’ve still had to throw my lollipop in the sandpit a few times in recent years.

Permissions – obviously if you’re using someone else’s work, such as images, these need to be cleared. Sometimes this can be expensive – the images in The Birth of Territory, for example, ranged from really expensive to free, with no obvious correlation between source, importance and cost. What is perhaps less known is that if you, the author, are reusing work you’ve previously published, you also need to get permission. Some publishers are straight-forward on this – Sage, for example, have a website which clearly sets out what you can and cannot do with your own work that has appeared in their journals. To republish or reuse an article in a book you have written or edited can be done with simple acknowledgement and no official clearance. Other publishers want a lot of information, and can take a long time to give you permission. Some have subcontracted agreeing this out to a third-party that charges a fee even if permission is freely given. It all reminds me of liner notes to, I think, a Radiohead album where it said ‘lyrics printed by kind permission, even though we wrote them’. Exactly.

Copy-editing – even the best of us need a copy-editor. Not only do they shoe-horn your book into whatever peculiar style the press has concocted, they also catch grammatical issues, standardise spelling (UK vs US) and compound-words etc. I hate it when copy-editors try to rewrite the text; I am grateful for any comment that something is unclear or all the many small things that good copy-editors fix up. The experience I’ve had at Polity has been very good, and the one I had at University of Chicago Press was also excellent. But I’ve also had some terrible experiences. I want to see, in track-changes, every change made to the text. If I read a sentence and don’t recognise it, and realise it’s been rewritten to say more clearly something different to what I said, then we have a problem…

Proof-reading – is hard work. As author, you know the text better than anyone, and you will see on a page what you think is there, not what is there. The other problem, and I have sympathy for presses here, is that many authors want to rewrite a book at this stage. You have got to correct the printing of the text you provided, as agreed at copy-editing. Some presses have someone other than the author go over the proofs as well, such as the copy-editor. More should do this. I’m continually amazed by the poor state of some printed books. But then, one of my own books had a very odd error in the printed version, which was never in proofs that I was sent. No idea how or when it got there. There is only so much an author can do.

Index – as electronic access becomes more and more common, this is perhaps becoming less important. But books still, by and large, have indexes. Some authors do them themselves. I did once, and never again. Not only was it difficult, time-consuming, and – I thought – incredibly dull, I also realised that the author is probably the worst person to do this. The index is for a reader, of course, and that person isn’t going to encounter the text in anything like the way the author does. Anyone who uses an index to read a book (as opposed to checking a detail in a book they’ve already read) is hardly an ‘ideal reader’. An author will probably find that they have been terminologically or conceptually imprecise when they compile an index, and there is little they can do – the index is done with page proofs to have correct pagination, and proofs can only be lightly amended. So I’ve used PhD students or other career people who need some additional income to compile indexes, to variable degrees of success. More recently I’ve been using a professional indexer, recommended by a friend and colleague. She did Foucault’s Last Decade and will do Foucault: The Birth of Power too. Sometimes presses say they can arrange an indexer and, if they are feeling generous, offer to set this against royalties. Be warned that unless your book does reasonably well, the cost of the index may easily be more than the royalties you’ll receive. I really think publishers should incorporate the cost of an index as part of the production process for a book, but they don’t. It is a terrible irony than the indexer or copyeditor of a book may well earn more from it than its author. Their work is important certainly, but it is a few weeks work at most. And yes, most academic authors are on a salary, but not all, and few can write books in standard contracted hours.

Author-questionnaire – of course, publishers have marketing departments, but I think more and more is being devolved to authors. So authors have to provide a detailed list of journals that might review a book, academics that might adopt it, conferences at which it should be promoted, etc. Doing this properly takes time. Authors generally have to write their own backcover blurb, which is then sometimes sent back by marketing with terse comments but no alternative suggestions. Authors often have to suggest who should endorse the book, though the publisher has to lead on this. Increasingly now, books are sometimes sold in individual chapters as well, so you may have to write an abstract for sales purposes for each component part. (I didn’t like doing this, and didn’t like the idea of the book being chopped into pieces – if I’d wanted the pieces available individually, I’d have published them as articles.) I had to come up with a number of tweetable summaries of the Foucault book for use in social media. You may be asked to provide a text for the publisher blog, or a video abstract or similar. All important and all largely dependent on the author.

Copies of the book – you’ll often get a single advance copy of the book, followed by a few additional copies from the warehouse. I’ve always also bought several more copies, albeit at a small author discount, in order to give them away. Writing a book incures debts, and I try to give copies to people who have been especially helpful. Some image providers require copies of the book, and authors have to provide these at their own cost. Archives sometimes make use of their material conditional on receiving a book. Colleagues, ex-supervisors, friends, family… Some publishers allow you to set the cost of additional copies against royalties; others don’t – in part because they are not sure the royalties will cover the cost.

I think those are the key things in the process from acceptance of final manuscript to seeing the final physical object (or, I suppose, e-book file). Writing the two Foucault books back-to-back means I’ve barely finished the production process for one than it begins again for the second, and Polity are comparatively fast at around 9 months from final acceptance to publication. If these had been with US university presses the first would just be further ahead in the process than the second at this stage.

As I said at the beginning, these are one author’s experiences of the process. A publisher would, of course, see a different side of this, and know of things that authors have no experience with. But from an author side, there is a lot of work to be done after the exhilaration of finally getting a manuscript into production.

Comments, additions, and other experiences very welcome…

Pingback: Nathalie Sowa, ‘Ten Things I’ve Learned Designing for a University Press’, University of Chicago Press, Blog | Progressive Geographies